In 1961, the Honey Dew Restaurant, on Rideau Street beside Union Station, offered a front-row seat to watch the cruising on Mackenzie Avenue. Credit: City of Ottawa Archive

This article was originally published in the June 25, 1999, edition of Capital Xtra. Credit: Xtra Ottawa

Looking back over his 57 years, Paul (he doesn’t want his last name revealed) says his upbringing was typical of that of many gay kids — parents who didn’t get along and were often absent.

His mother was a party girl who often left him alone at night, so as he hit puberty, his comings and goings were quite unregulated.

Living in Buckingham, Quebec, he went to a Catholic school where he was taught by religious brothers. It was at that school that he had his first sexual encounter, with the choir master, a lay person.

“When I look back, religious life at the time was repressed. I was sent home on several occasions from school for wearing short sleeves. It was a puritan time. Those religious men were not allowed to have sex and were surrounded by young boys who were often looking for affection.”

Paul also began to work in a store run by a man who was known to be gay. Being young, Paul perceived him as an old, ugly, fat man. The man used his store and its chips and drinks to lure boys. Although he never made sexual advances to Paul, people assumed otherwise.

“When you are an effeminate boy — and I was — people seek you out more. I was approached by other men and had sex with them many, many times. I did not take it seriously. It just happened. Looking back to those years, the 1940s and 1950s, men were afraid to live openly gay lives. It was considered dishonourable and brought shame to your family. You were the lowest echelon of low life, but it definitely existed, even if it was largely underground.”

Paul’s world changed when he came to Ottawa to visit his grandmother. On a whim, he went to the Château Laurier to use its swimming pool. There, with its open changing room and steam room, he saw that there were possibilities for sex between adult men.

Shortly afterward Paul moved to Ottawa. He had dropped out of school in Grade 9 at age 14, despite a grade average of 70 percent. He had been told that as he did not have 70 in every subject, he would fail his year. Incensed, he never went back to school but worked at odd jobs. At 16, he decided he had to have a career. As his grandfather and father were barbers and his mother a hairdresser, he chose to follow in their footsteps.

“When I came to Ottawa, I intended to be a barber, but there was only a hairdressing school, so I went there. On my first day, I realized my life would no longer be a nightmare. I would never be the odd one. I was like a bird that had learned to fly. In school for nine years, I had been ridiculed, laughed at and called names.

“But even though people at the hairdressing school were more open, homosexuality was still an issue. You have to remember that in the 1950s you couldn’t say you were homosexual. Despite what I had seen at the Château, it still hadn’t occurred to me that there was an organized gay world outside. It was when I finished school and began to live on my own that I slowly began to find the sexual meeting places around Ottawa. Suddenly, I realized there was a gay lifestyle.”

Paul moved to Hamilton in the early 1960s, and shortly afterward, two men with whom he had gone to hairdressing school joined him there. In order to save money, the three lived together.

“Those two men showed me how to become a screaming queen. They taught me how to dye my hair and pluck my eyebrows. I went to Toronto to Lettros, one of the first gay bars in Toronto. There, the men wore sports jackets and ties. They didn’t dance — just sat at tables. They didn’t cruise much because Toronto was a bath city. After you went to the bars, you went to the steam baths. That’s where the sex happened.”

Paul moved back to Ottawa in 1961 and discovered the old Honey Dew Restaurant, on Rideau Street beside Union Station. It offered a front-row seat from which he could look across Rideau Street to the cruising on Mackenzie Avenue.

“The Honey Dew — we always went there at night. Its décor was very ’50s-ish: booths, cafeteria-style, painted orange. It was a place where gay men could socialize. We were young and had no money, but the manager and staff never asked us to leave. I’m not sure why. Maybe it was the ladies in the kitchen who were sympathetic, or maybe it was simply that being on Rideau in the middle of nowhere and at night, they didn’t have much of a clientele and tolerated us.

“The restaurant had large windows in the front that looked across to Mackenzie. When we were finished, we went directly across to cruise. We weren’t prostitutes, just young gay men out for adventure and looking for sexual partners. We were queens. It was ‘in’ to be a queen then. At least, it seemed that queens were the only ones you met on the streets — and if one queen saw another all dressed, made up and fixed up, well, you had to do it too. You had to be wild and flamboyant to be noticed by the more masculine guys who drove their cars up and down the street.”

Paul says that at that time homosexuals had to be obvious when they cruised at night. They wore makeup, dyed their hair and had tight pants. It was the only way closeted or bisexual men would know you were gay.

But Mackenzie was not the only street where cruising took place. Paul says that Bank Street, from Wellington to Somerset, was notorious. A queen would walk up and down Bank Street and the cars would slow down and check her out. There was always the potential for physical abuse.

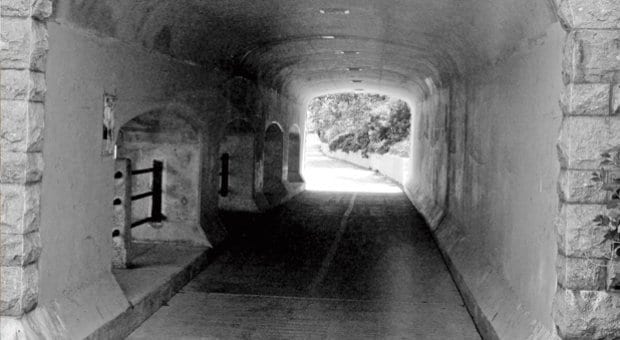

The most sexually active place at the time was along the Rideau Canal, Paul says. From Somerset Street to the Pretoria Bridge, there was an abundance of greenery and trees, which allowed men to have furtive sex. In comparison today, he says, there are hardly any trees. Of course, there were also Major’s Hill Park and Nepean Point.

In the 1960s, male hair-dressers — who were seen as artists — were sought after because as gay men, they had panache and style. They were at the forefront, leading the way for the gay men of today. They went to work in suits and ties but with dyed hair. They were seen as flamboyant and therefore exciting and entertaining, Paul says.

“If you were gay then, you had to be strong — either physically or verbally. I was never strong physically. I was French and didn’t know English. I had to learn it. I wasn’t educated. It took several years for me to develop my gay identity. Gradually, I decided to stop wearing makeup, that this was the wrong route to take. As I met different types of people, I realized there were a lot more people than the cruisers with four pounds of makeup and no social life.

“I began to understand that a strong personality, a great wit and super looks were the only way to go. You had to be the best looking, the slimmest — all the things that homosexuals revered. There was quite a social life in Ottawa. There were home parties, dating . . . a more active life than just the streets.”

Ottawa, as the nation’s capital and as a civil-servant town, was still reeling from the Cold War and confessions of espionage by Russian defector Igor Gouzenko. Those events led to an investigation by the RCMP of gays in the civil service. People, Paul says, were afraid — afraid to get involved, afraid they would be identified.

“I was questioned because my name had been given by several RCMP paid informers. The RCMP showed me photos of people, including myself, at house parties, of clients leaving the Rialto on Bank Street, which was the movie theatre where gays went at that time. They wanted me to identify people, but I refused to name anyone. I was told I was a traitor to my country and an enemy of the government, but I wouldn’t budge.”

Despite the fear, life went on, albeit quietly. The late 1960s were followed by gay liberation. A large part of Ottawa’s gay history took place in the clubs — Coral Reef and the Chez Henri. Paul says he has never seen dancing like he did at “the Reef,” a large, friendly club. The Chez, however, was another story.

“The Chez Henri was a shady place and very, very tough. It was owned by a millionaire named JP Maloney. In its heyday, in the ’30s and ’40s, it had been one of the biggest straight bars in the region and drew big-name performers. Upstairs was the show room; downstairs the tavern. The tavern was always a working room for prostitutes. In the 1960s, the Chez was at its lowest point of decline. Maloney was still alive, living as a recluse on the top floor. He didn’t like gays but tolerated them because they were business. Only openly gay men would go to the Chez — to be seen there left no doubt about your sexuality.”

At first, gay men were allowed only in the tavern, which was open seven days a week. There were often brawls between straight and gay men in the tavern. Later, Paul notes, gay men were allowed into the Salon d’Or, a lounge with a stage in the middle and tables on either side. For some unknown reason, gay men sat on the left side of the stage and the straight men on the right. If you were downstairs in the tavern, you could wear jeans, but if you went to the Salon d’Or you had to wear a shirt and tie.

“It seems to me that gay men didn’t go for gay men at that time. Many gays spent a good deal of their time in the cans to have those gorgeous heterosexual men. I think in the ’50s and early ’60s, women didn’t perform oral sex and gay men did.”

“The biggest change came in the 1980s, when homosexuality became the newest wave. There were many bisexual men who came out into gay life and many straight men looking for a good time. They had no fear of getting a woman pregnant and they didn’t have to spend money on gay men as they did on women. It was the very best time for homosexuals, but the worst time followed the discovery of AIDS. Gay men went back 50 years in shame after AIDS arrived.”

Looking back, Paul says the biggest misconception in gay history has been the role of the bars. In previous decades, bars played an important role and were places to socialize. When men went out, they went from table to table, introducing themselves. When men asked men to dance, they didn’t say no.

“We had a great social time. Now, when people come into the bars, they come in alone, stand alone and drink alone. Then they go to the baths or get onto the internet. There’s nothing less social than spending your time with people you don’t know or can’t see.”

To celebrate Xtra’s 20 years of publishing to Ottawa’s gay and lesbian community, we’re digging through our archives to reprint a selection of noteworthy stories that highlight our community’s rich history. “View from the Honey Dew” first appeared in Capital Xtra #70, June 25, 1999.

Also in the series:

Charlotte Loved Margaret: Was Ottawa’s Former Mayor in a ‘Boston Marriage’?

Marching Forward: (The First) 25 Years of Gay and Lesbian Activism in Ottawa

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra