Andrew Shopland Credit: Courtesy of Andrew Shopland

Lau Mehes Credit: Courtesy of Lau Mehes

Trevor Loke Credit: trevorloke.ca

Floyd Van Beek Credit: Courtesy of Floyd Van Beek/Jo B photo

Peter Breeze Credit: Shimon Karmel

Joshun Dulai Credit: Courtesy of Joshun Dulai

Yogi Omar Credit: Courtesy of Yogi Omar

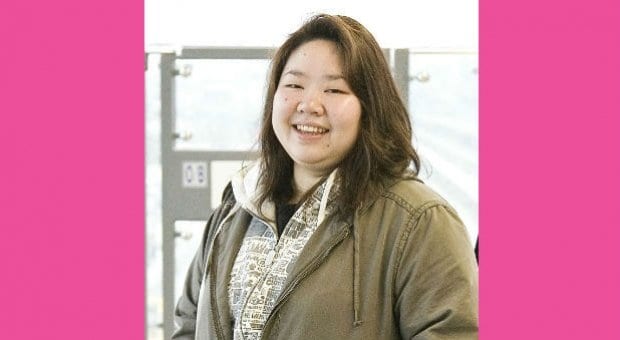

Jen Sung Credit: Courtesy of Jen Sung

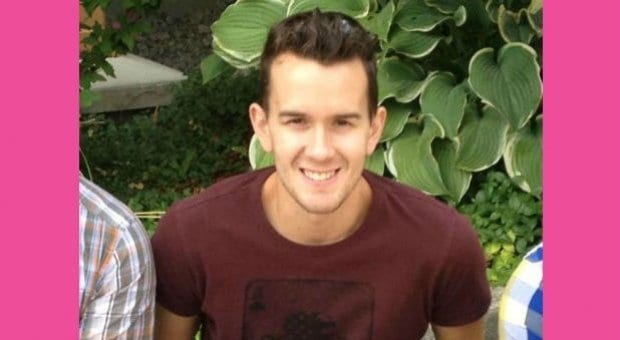

Ryan Clayton Credit: Courtesy of Ryan Clayton

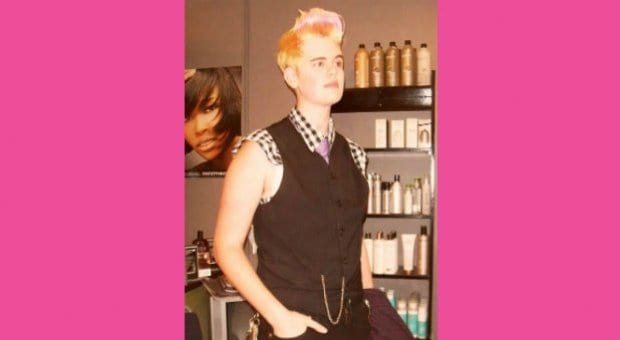

Kasey Riot Credit: Facebook.com

David Le Credit: Courtesy of David Le

Kim Villagante Credit: Janet Rerecich

Cal Mitchell Credit: Courtesy of Cal Mitchell

Leada Stray Credit: Dan Rickard

Cellouin Eguia Credit: Courtesy of Cellouin Eguia

Brandon Gaukel Credit: Alvin Grado

Lydia Luk Credit: Christine McAvoy

Jaedyn Starr Credit: Courtesy of Jaedyn Starr

Brad Therrien Credit: Courtesy of Brad Therrien

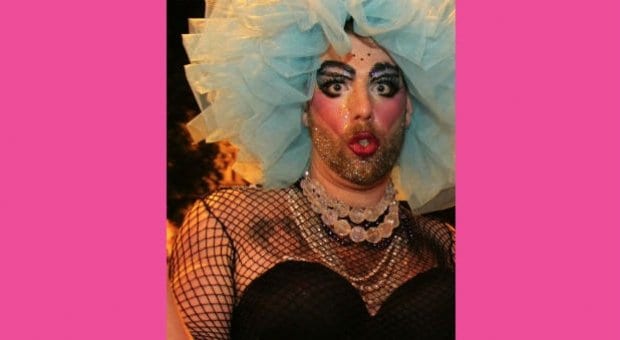

Pussy Liquor Credit: Courtesy of Pussy Liquor

Cory Oskam Credit: Courtesy of Cory Oskam

Shaun Hunter-Mclean Credit: Courtesy of Shaun Hunter-Mclean

Isabel Krupp Credit: Facebook.com

Carven Li Credit: belle ancell

Ander Gates Credit: belle ancell

Paige Frewer Credit: belle ancell

John Kuipers Credit: belle ancell

Melanie Matining Credit: belle ancell

Dave Deveau Credit: belle ancell

Justin Saint Credit: belle ancell

Welcome to Xtra Vancouver’s Top 30 Under 30!

For the next 30 days we will unveil BC’s best and brightest young queer leaders. Meet the activists, artists, organizers and educators who are building our community on a daily basis.

Nominations were solicited from a wide cross-section of community members, including many of the nominees themselves.

The rankings are based on all the nominations received and each person’s contributions to our community. The countdown isn’t meant to be viciously competitive; more of a fun competition in the context of celebrating each and every one of the Top 30 Under 30.

Who will be #1? Tune in every day until the big reveal on Oct 9, and join the discussion on our special Facebook event page dedicated to this project.

The next generation begins now.

#30: Andrew Shopland

According to Andrew Shopland, being part of the gay community isn’t just about making friends and having fun; it’s also good for your health.

“We know from local research that gay guys who are more connected to community have significantly better health outcomes,” the 25-year-old says.

Shopland is the recently hired project coordinator at YouthCO’s Mpowerment, a youth-focused peer-support program that hopes to broaden HIV education through workshops, social events, information sharing and activities in social spaces outside of bars, clubs and other traditional gay venues.

“Once someone is established in the gay community and has a group of friends, then they can create that sort of space informally,” he says. “But for people who are newly out or new to the city, or just don’t have that social network yet, it’s a point of entry into the community.”

Before landing at YouthCO, Shopland was an active volunteer in Victoria’s gay community. He was a coordinator for the Pride group at the University of Victoria (UVic) and was involved in starting UVic’s positive-space network.

He’s most proud of co-founding the Creating Connections events that aimed to connect Victoria’s various gay groups.

“There was the student groups, a group for senior lesbians, a group for middle-aged gay men, but they never really interacted the rest of the year,” he says. “It was also meant to create intergenerational community. The groups were segmented by identity but also very much by age. I realized I only knew people in their 20s.”

***

#29: Lau Mehes

While working at the University of British Columbia, Lau Mehes kept overhearing her officemate talk about the work she was doing as the director of CampOUT, a summer camp experience for queer, trans and allied youth.

So when the opportunity arose for Mehes to lead workshops with the camp, she jumped at the chance.

“I felt lit up. It was some of the most meaningful education work I’d ever done,” the 25-year-old says.

At that moment she knew where her future would lead. “I said, ‘This is what I want to do. This feels so amazing.’”

She’s now been a youth worker with Qmunity’s Gab Youth program for the past year.

“It’s really empowering for me, as someone who still identifies as a youth, to be able to create youth community, to have a space for youth to go where they can feel safe and feel really celebrated for who they are, for exactly who they are, and not who they should be,” she says.

She still remembers the intense nervousness she felt at her first drop-in as the new Gab worker, as she wondered whether the youth would like her and want to be around her.

“[They] were so welcoming. They asked the most meaningful questions: ‘Why do you want to do this work? What are some of the things that drive you?’

“I just knew that I’d come across something so special,” she says.

Mehes believes that Gab serves an invaluable purpose for queer and trans youth in Vancouver.

“It’s a powerful thing for them to walk in and find the kind of community that they need and to find other people their age who are feeling what they’re feeling, and feel like they can be understood.”

***

#28: Trevor Loke

Despite his youth, Trevor Loke is already something of a political veteran.

In 2011, at the age of 22, he became the youngest-ever elected official in Vancouver history when he won a seat on the city’s parks board under the Vision Vancouver umbrella.

“I believe everyone should consider giving public service a shot at some point,” he says. “It’s an incredible experience to be able to work for people and help them with issues that affect their day-to-day lives.”

Before becoming a parks board commissioner, he was a director-at-large on the provincial council of the BC Green Party and worked as a constituency assistant for Delta South MLA Vicki Huntington and as an aide to former Surrey North MP Chuck Cadman. He also ran unsuccessfully as a candidate for the Green Party in the 2009 provincial election.

Since taking office, he’s pushed for more inclusive policies for trans and gender-variant people in local parks and recreation facilities.

“Of course, I considered myself as part of a broader set of communities, but my experience and understanding of these communities was most deeply rooted in my experience as a white, gay male, an experience of privilege,” he notes.

Along with the policies, he helped create a community working group to address some of the barriers preventing trans and gender-variant people from comfortably accessing parks and recreation services.

Loke, now 24, says he looks forward to working on the group’s recommendations when it completes its report in April.

“When I began to learn of the various barriers to access which existed for our trans and gender-variant communities in Vancouver, it became apparent to me that we had left the ‘T’ behind, both as a broader queer community and as a society,” he says.

“This community is my family, and it’s an incredible family to be part of.”

***

#27: Floyd Van Beek

“I want to share my thoughts with the world,” says spoken-word artist Floyd Van Beek.

“It relies equally on a balance of your performance and your writing,” the 18-year-old says, explaining the virtues of the art form. “I can communicate my own identity in a better way than merely writing something on a piece of paper and expecting people to see it.”

Van Beek, who prefers the gender-neutral pronoun they, performed in this summer’s Queer Arts Festival in Vancouver, both at the opening-night gala and as part of the youth showcase, Fruit Flambé.

The culmination of a six-week program where five queer youths were mentored by hip-hop artist Kinnie Starr, new-media artist Sammy Chien and playwright David Bloom, the showcase opened Van Beek’s eyes to the possibilities of collaboration. “By the end, it felt like we were a small community of queer artists.”

Van Beek believes that sharing art in queer spaces is a vital part of the success of the entire community, especially one that is constantly shifting, changing and learning.

“Within the queer community, there’s so many different kinds of people, and art, as such an intense form of expression, allows people to really think and feel through someone else’s eyes,” they say.

They first discovered their affinity for the written and spoken word as part of a club in their suburban Tsawwassen high school.

“I write really silly love poems, and I write poems about how if we could fart in front of one another we’d have world peace,” Van Beek says.

“But when I write poems, my identity, and my sexuality and my queerness — because being queer is such a huge part of my life right now — it does find its way into most of my art.”

***

#26: Peter Breeze

Vancouver singer/songwriter and event producer Peter Breeze has come to terms with being known as a gay act.

“Being called a gay artist is fine by me because I’m not ashamed of it, but it’s kind of limiting and it’s putting me in a box,” says the 27-year-old co-producer of such events as the underground rave DUI, Half n Half, celebrity-themed parties Club La Lohan and Club La Spears, and Spice World nights at the Rio Theatre.

As a singer, Breeze says his toughest critics have been part of the gay community. “I’ve found it hardest to convince them to take me seriously and put them in the same place in their minds that they put other artists. We really want the equality, but we also eat our own. They don’t want another gay person representing them if they don’t feel like they can identify with them.”

He’s also weathered his fair share of anonymous online detractors.

“If I went by the things that people have written about me or said about me online — I mean, you would think that as soon as I walked out of my house someone would be throwing fucking tomatoes at me,” he says wryly.

“But then when I do have a show or release a video, people come out and there’s a huge support system there.”

After five years of devoting most of his energy to his music, Breeze is now pursuing other passions, such as event production.

He’s optimistic about the buzz in the local gay community and the creativity he’s seeing in the clubs. He sees the underground scene as a place where artists can go to experiment with their sounds and experiment with their looks before hitting the mainstream.

“The underground scene in Vancouver is really blossoming, and I think that was the thing that Vancouver was missing for a long time,” he says.

***

#25: Joshun Dulai

Joshun Dulai is still getting used to sometimes being recognized by strangers.

As one of the models on the Punjabi-language poster for Our City of Colours, a Vancouver non-profit that promotes the visibility of LGBT people in cultural communities, Dulai’s face represents queer people to one of Vancouver’s largest ethnic communities.

“Apparently, it’s [Our City’s] most requested poster,” the 24-year-old says. “My dad, who’s a teacher, said he saw it in his high school.”

Dulai didn’t come out until university, a fact he attributes to his own personal journey rather than to external homophobia.

“I was a very shy and awkward person back in the day and just really confused throughout high school,” he says. “It had nothing to do with people being homophobic. There were people who were out of the closet in my high school. My parents had gay and lesbian friends, and growing up I knew they’d be accepting.”

Dulai is the newly hired coordinator for Totally Outright, an annual leadership program for 25 young gay men focused on gay men’s health issues, such as coming out, gay sex, harm reduction and outreach work.

“We talk about things that a lot of gay guys don’t get to hear information about directly from experts. You don’t really deal with gay sex in high school; it’s all very heteronormative,” Dulai says.

“We talk about gay relationships. If you’re just coming out or you’re new to the city, it’s a very good way to learn about these things, develop self-confidence and make social connections.”

He is also planning the one-day Stepping Out youth conference, which will be held directly after the Community Based Research Centre’s annual Gay Men’s Health Summit in November.

Dulai credits the Totally Outright program for his passion for giving back.

“Trying to change things for the better and trying to help improve other people’s lives is when I started feeling part of a community.”

***

#24: Yogi Omar

When Yogi Omar turned 30 in February, there was only one thing he wanted to do for his birthday: throw a fundraiser for Out in Schools.

“I always feel selfish when I’m having my birthday party because I didn’t really do anything to be born,” he says. Though originally he had planned to invite 100 people, the final guest list ballooned to 400.

Omar has volunteered with and supported Vancouver’s Queer Film Festival for the last 10 years: as a venue coordinator, as a programming coordinator, as a board member and now as a donor.

The festival’s educational arm, Out in Schools, is especially important to him since he remembers how difficult it was to be a gay teenager.

“Back in high school, I was a bully,” he says. “My best friend came out to me and I bullied him. It was horrible. Deep inside, I was scared that people would find out I was gay.”

He sees supporting causes like Out in Schools as an opportunity to fix some of the mistakes he made in the past.

“If [youth] have positive role models or positive images of gay people, it will definitely help gay students in those schools,” he says.

“I feel like movies and music are the most efficient way for people to reach other people.”

In August, Omar organized a kiss-in in front of the Russian consulate to protest Russia’s anti-gay laws and to stand up for human rights as Vancouver stepped into Pride mode. He organized an even larger kiss-in for the opening night of the Queer Film Festival.

He has also been heavily involved in local choirs over the last decade: five years with the Glass Youth Choir, one with the Rainy City Gay Men’s Chorus and the last five with the Vancouver Men’s Chorus.

The It Gets Better video that he produced for the Vancouver Men’s Chorus in 2011 recently hit 20,000 views on YouTube.

“With choirs, it’s a sense of community,” he says. “When I first joined 10 years ago, I joined because it was a gay group and I wanted to see where I fit in and where I belonged. But then I stayed mostly because of the music, because I believe that you can change the world with music.”

***

#23: Jen Sung

She may not be able to pinpoint the year it happened, but Jen Sung will never forget the way she felt when she saw her first gay film on the big screen.

Sung remembers driving from her parents’ home in Port Moody to a Queer Film Festival screening of a Taiwanese film at the now-closed Tinseltown theatre in Vancouver.

“I was just blown and floored,” she says. “From then on I was like, ‘I’m forever dedicated to this work, and I want to be involved in it in any way possible.’”

After stints working with the Asian Society for the Intervention of AIDS (ASIA) and Women Against Violence Against Women (WAVAW), Sung is now the program coordinator for Out in Schools. She leads a team of facilitators who use films to discuss queer issues, homophobia and bullying in classrooms across the Lower Mainland and in rural BC.

“It’s about harnessing the powerful medium of film and video and media as a way to engage young students and youth in a discussion that is otherwise seen as sensitive in nature,” the 27-year-old says.

“After a presentation at a school, an ally or a student will come up to me, sometimes in tears, because they have never seen an Out in Schools presentation or haven’t heard anyone say the words queer or gay or lesbian out loud in front of their whole school.”

Sung has also recently joined the board of Our City of Colours, a group she hopes will continue to make a difference for young queer people of colour.

“As a young person and as a woman of colour, I didn’t see a lot of positive representation growing up in the Lower Mainland. I think that we can help change that.”

***

#22: Ryan Clayton

Ryan Clayton was bullied long before he came out on his 16th birthday.

A foot shorter than most of his classmates in the rural town of Salmon Arm, he was a frequent target for verbal and physical attacks throughout elementary and high school.

“I was already so downtrodden it almost didn’t matter,” he says. “It was like, what worse can you do to me that hasn’t already been done.”

Still, he says, coming out was “terrifying.”

“I was worried my parents would kick me out. I was worried that my classmates would reject me, and some of them did. There were quite a few people who never spoke to me again.”

It’s from these experiences that Clayton has drawn over the last seven years as an advocate for anti-homophobia policies in public schools and as a facilitator of anti-homophobia workshops in more than 500 classrooms across British Columbia.

He started off by joining Qmunity’s PrideSpeak program, which trains youth to conduct workshops for other youth in Metro Vancouver.

He later reached out to his old school district and asked if he could speak at his former high school. That led to an annual tour and more engagements at other nearby schools in the North Okanagan and Columbia River regions.

“They keep asking me to come back,” the 26-year-old says.

“Because I’m from a small town, it meant way more to me to go out and reach out to rural communities,” he says.

A former co-chair of the City of Vancouver’s LGBTQ advisory committee and co-founder of the Purple Letter Campaign, Clayton continues to press the provincial government to enact a provincewide policy to address homophobia in BC schools.

He says small-town schools are no different than those in urban areas when it comes to being safe or unsafe spaces for youth who are different. But issues concerning sexual orientation and gender identity are often less discussed at home or in school, he notes.

“We like to think, with the information age and the internet, that we have tons of access to information, but you still have to know what to look up,” he says.

“In urban areas, even if people are uncomfortable with it or actively against gay rights or gay issues, they tend to have had that discussion already.”

***

21: Kasey Riot

DJ Kasey Riot remembers her first time sneaking into a gay bar, at 16.

“[Lick] was the only place you could get in underage. I remember it being really magical,” she says, laughing.

“I walked in and it was like there were all these other gay people. It was just so nice to get away from the boring, mundane suburban world and have fun with other like-minded people.”

It was at the clubs that she started hanging out with the DJs who would eventually become her mentors.

“I got obsessed with it,” the 25-year-old says. Her mother was a piano teacher who taught all her kids music. Riot moved from the piano to the guitar to the drums, before eventually settling on DJing and producing electronic music.

Riot DJs every Thursday at The Junction, monthly at The Cobalt’s Electric Circus, at Hershe’s long-weekend parties, and is a resident DJ at Sin City Fetish Night. She also hopes to release an electronic album within the next year.

She says that when Lick, Vancouver’s last lesbian bar, shut its doors in 2011, it was a sad time but that there was a hidden silver lining.

“Most of the people who had been involved [at Lick] started throwing their own small parties. In a way, it was a blessing in disguise. It made people branch out and be more creative instead of doing the same thing every weekend.”

She says the drag-king scene has flourished, and many of Lick’s female DJs began getting more attention and started playing at other bars.

“Before, I only played for lesbians, but I had so many gay friends that it was great to play at the gay-boy bars. It’s a different vibe; you have to play different music. It forced me to branch out and learn new things.”

Though Riot appreciates all of her success, she says the best part of being a DJ is feeling part of a bigger community.

“There’s more to throwing events than just getting drunk and having a good time; it’s about bringing people together.”

***

#20: David Le

David Le never thought he’d end up researching gay men’s health as a career. “It’s something I fell into,” the 25-year-old says.

After answering a call to participate in Totally Outright, a four-day leadership workshop for young gay men, he soon found himself hired as the youth team leader for the “Investigaytors” at BC’s Community-Based Research Centre (CBRC).

Launched in 2011, Investigaytors is a hands-on training and education program designed to give young gay men knowledge of and skills in researching gay men’s health issues and to help foster the next generation of researchers.

Approximately a dozen young men have enrolled in Investigaytors since its inception.

Before starting his current position, Le studied psychology and critical studies in sexuality at the University of British Columbia.

He explains that while a good researcher doesn’t need to be part of the community being studied, there are some benefits.

“There’s an advantage to actually knowing and having a lived experience as a gay man that helps frame the perspective a bit better,” he says, pointing to nuances of language that might be lost on a researcher who is more rooted in academia.

According to Le, the CBRC’s research plays a critical job in filling gaps around gay men’s health. “That’s where research really shows its value, when [we’re] able to translate that information that’s been collected back into the community.”

***

#19: Kim Villagante

As an artist, Kim Villagante doesn’t like to limit herself.

“I’m not just a visual artist; I’m not just a singer — I do a lot of things,” the 24-year-old says.

The self-described multidimensional artist and singer/songwriter experiments with rap, poetry, spoken word, painting, drawing and acting. She is currently working on an album slated for release in early 2014, and this fall, she’ll spend six weeks in Montreal acting in a hip-hop musical.

“It takes this powerful medium of hip hop and critiques the homophobia, racism and sexism within itself.”

She struggles with the idea of being a queer artist. “I wouldn’t say that I am an artist that creates queer art; I just happen to be queer, and inevitably, my queerness comes through in what I create or what I talk about in my music.”

The isolation she felt growing up in suburban Surrey subsided after she moved into the city.

“The artistic community is very small, but I feel a huge amount of support,” she says.

As someone who is learning to understand her own identity — as queer, as Filipino, as having ancestry in another country but being born and raised in Canada — she sees her art and her activism as one and the same.

“That is my form of activism: storytelling. Better understanding yourself and seeing how it connects to the whole.”

Part of that connection means giving back to the community and using art to support others.

Last year, she worked as a facilitator for Qmunity’s Routes to Roots, a program for queer youth of colour and immigrant youth, and she also organized a conference for queer women of colour. This summer, she mentored six youth in spoken word through the non-profit ArtQuake organization.

“For once in my life, I feel like there is a real community of support.”

***

#18: Cal Mitchell

Working behind the scenes as the office coordinator for UVic Pride, the campus collective at the University of Victoria, Cal Mitchell is happy to be out of the spotlight.

Before that, Mitchell, who prefers the gender-neutral pronoun they, sat as the Pride representative on the board of UVic’s student society for a tumultuous year and a half.

“You’re almost expected to be the voice of all queer people on campus, so if there’s a queer person who disagrees with what I’m saying at a board meeting, there can be conflict,” the 21-year-old says.

UVic Pride has taken pro-choice positions and also stood against homophobic pamphlets distributed by a religious group on campus. According to Mitchell, some of those stances drew unwanted attention from rightwing media outlets and the white supremacist hate group Stormfront.

Mitchell now provides administrative and moral support and is glad to be offering resources to students and the larger Vancouver Island community.

In addition to providing safer-sex supplies and pregnancy tests, UVic Pride also carries samples of chest binders and prosthetic penises that can then be ordered for trans members on an affordable sliding scale.

“I believe we’re the only queer group on [Vancouver Island] that has dedicated funding. People in the community will come to us requesting money for different events,” they say. “We’re not just for students, we’re a community collective.”

***

#17: Leada Stray

Under a cover of misting rain, Leada Stray addressed a crowd of about 80 in front of New Westminster City Hall in January at a rally to demand justice for January Marie Lapuz, who was killed last fall.

Stray, who prefers the gender-neutral pronoun they, co-organized the rally with the Transtastic Coalition for Equality.

Lapuz’s alleged murder struck close to home on several levels. Stray waited for the community to react but was disappointed by the perceived quiet.

“I kept waiting for people to stand up, for people to say something, to display any kind of concern,” the 30-year-old says. “I talked to some other trans fellas, and we decided to speak up. It was a matter of brothers standing up for sisters.”

Stray was equally disgusted by the behaviour of law enforcement officials.

“They were using her wrong name; they were using the wrong pronoun.”

“These are the people that are supposed to protect us, and yet they are the same people we live in fear of, because we never know whether we’re going to get a police officer who paid attention in sensitivity training. That shouldn’t be.”

Five years ago, Stray was very involved in the gay and trans communities but eventually took a step back, partially because of friction related to being a female-to-male trans drag queen.

“It does get tiring,” they say. “I’m teaching people that yes, I’ve transitioned; no, that doesn’t mean that I want to be a woman again. It means that I’m a man in a dress.”

“The style of performance that I do is very in-your-face, and it can be draining to be a storyteller in a world that doesn’t want to hear it.”

Now a postulant with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, Stray is ready to give back again.

“When I first came out, I had help. I had a group of older gays and lesbians and transgender people who took me under their wings,” they say. “They taught me about what life as a queer person could be, they taught me about joy, and they showed me hope where for me there wasn’t any.

“The next generation might have it easier than we did, but they still need help. Just because we live in a technological world, it doesn’t mean that we don’t need community.”

***

#16: Cellouin Eguia

When Cellouin Eguia emigrated from California to finish high school in Metro Vancouver, he had a picture-perfect idea of what his new life would be like.

“I came to Canada being excited about how much easier and more accepted I was going to be, and then the very first year I was here, I ended up going to a protest about the anti-bullying policy,” he says.

Eguia moved to Burnaby, BC, just as a group of concerned parents affiliated with a local church were protesting the introduction of an anti-homophobia policy in the district’s schools.

“I saw there still was a lot of work to be done,” the 18-year-old says. “I found there wasn’t a strong visible LGBT presence at the high school.”

Eguia restarted and led Byrne Creek Secondary School’s gay-straight alliance (GSA) to take on a higher profile among the student body. The GSA fundraised for AIDS charities and for its eventual entry into the Vancouver Pride parade.

He also began volunteering with the Vancouver Queer Film Festival and its educational arm, Out in Schools, offering a perspective on the importance of youth programming to prospective corporate donors. This year, he also sat on the youth steering committee for the Rise Against Homophobia video contest.

“I did get a lot of crap in high school,” he says. “What helped me was knowing that there were people out there who had my back, or who were like me or were going through the same things.”

He says the film festival and other high-visibility queer events have given him real hope.

“As someone who grew up hearing stories about what it would mean to be gay or ‘if I led this lifestyle’ and the hurdles and obstacles I would have if ‘I chose to be this way,’ I was always scared about my future,” he says.

“At the festival, it was so inspirational and comforting to see successful adults who had made it through high school and who weren’t ashamed to be who they were. That feeling needs to be available for all queer youth in the community.”

***

#15: Brandon Gaukel

Once a month, Brandon Gaukel flies across the country to Vancouver to promote and perform at the East Vancouver parties he helped launch.

Gaukel moved to Toronto for work and for his husband, but he can’t, or won’t, let go of Vancouver. He spends three weeks back East and one week in Vancouver each month.

“It allows me to see all the people I love in one evening when I’m back in Vancouver,” the 28-year-old says.

Five years ago, he and business partner Dave Deveau launched a series of queer events on the Eastside, starting at the ANZA Club with Queer Bash. As artists, they were looking to create affordable events for themselves and their friends closer to their neighbourhoods, as well as to help fundraise for their other art projects.

“We’re definitely more grassroots, but we try to work within our budget,” he says.

The dress-up party Queer Bash has now been scaled down to a yearly Pride event, but Gaukel and Deveau have continued their tradition with Apocalypstick and, now, the monthly hip-hop party Hustla.

“Queer Bash and Hustla have always been a mixed crowd, and it gives a place for all types of genders and sexualities to hang out and celebrate,” Gaukel says.

“Everyone can feel welcome there: gay, lesbian, trans or straight couples that just want to dance to homo hip hop and watch drag queens. It’s definitely a lot more inclusive.”

In addition to his promoting duties, he also performs in drag as Bambibot.

“In the early days, I was just a sad, tragic mess of a drag queen — I wouldn’t even call myself a drag queen two years ago,” he says, laughing.

“[Bambibot] performed at the ANZA Club, and it was awful. I looked like my grandmother in drag. I got nervous, drank too much and forgot my words.”

Now he feels like she’s come into her own. “She’s fun, she’s a little bit slutty. I love making people laugh, and now she’s actually worth watching.”

Gaukel, who is also the founder and editor of the biannual arts and culture DIXX magazine and the founding creative director of Sad Mag, hopes to come back to Vancouver eventually on a more permanent basis.

“It’s my city; it’s my community. I fricking love it,” he says. “I see myself here in the future. I keep coming back because of the people.”

***

#14: Lydia Luk

Lydia Luk remembers finding her first queer space, at 17.

“It was me, the friend that brought me and two others. We were all in the closet, and we all went to the same school,” she says of the now-defunct Richmond youth drop-in group.

“It didn’t really feel like a community at that moment.”

Rather than let that experience deter her, she started attending the Gab Youth program in downtown Vancouver: first as a youth, then a volunteer, then as a youth worker and then as the program coordinator.

She says her journey out of the closet was slower than that of many of her contemporaries.

“When I first came to Gab, I was still living at home, firmly in the closet, and had no intention of leaving home. Almost all the other youth were on their own, because they had moved to the city or had been kicked out because of their sexuality.”

The first time she gave a workshop at a local high school, she used a pseudonym.

“Of course, I kept forgetting the fake name and wouldn’t answer to it, so halfway through I started using Lydia,” she says, laughing.

Now 29, she has spent most of the past decade organizing and facilitating in queer spaces.

“It’s my life. I can’t imagine not doing it.”

“People can call me an activist, but I think it’s really about caring about the people around me,” she says.

Today, she works full-time as a community organizer with PeerNetBC, providing training, resources and support to peer-led initiatives across the province. Her specialty is mentorship and training in anti-oppression work.

In addition to her day job, Luk attends Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU) in Surrey part-time and is the elected queer representative at her student union. One of her long-standing goals has been to launch KPU’s fledgling Positive Space Campaign.

“The easy part was getting the university to agree,” she says. “However, actually getting them to implement it has been a whole other set of challenges.”

“At most other schools, positive-space programs have been running for years already. The really sad part is that a lot of these schools already have other supports for queer and trans students, so positive space is just one piece of a larger pie,” she says. “At Kwantlen, that pie is basically non-existent, so the need is that much greater.”

***

#13: Jaedyn Starr

Jaedyn Starr grew up believing that the future was already set.

“I was supposed to be a Jewish girl who would grow up to be a straight Jewish woman,” Starr says. “I tried to be the person that’s called ‘normal,’ and it didn’t work.”

Starr (who uses no pronouns) first remembers feeling part of Vancouver’s larger queer community after attending an Amber Dawn reading at the Queer Arts Festival.

Spaces like those — where art and culture blend with queer elements — encouraged Starr to get involved with the Queer Film Festival and its educational arm, Out in Schools. “I feel the most welcome in organizations that are explicitly queer or trans. It’s a fun, entertaining and accessible way to bring ideas that may seem outside of the mainstream.”

As well as managing one of its theatres this year, Starr is the coordinator of the League of Diversicorns, the festival’s youth steering committee for its Rise Against Homophobia video contest.

The 26-year-old also delivers workshops independently that address issues of gender inclusion, body image and consent and is planning a countrywide workshop tour in the near future.

The work is very personal. “I tried to be a woman as hard as I could. I finally let that go and began to explore trans identities, and that has felt more natural and flexible and safe now that I have access to trans communities and trans friends.”

“Those assumptions that I put on myself ended up making it really hard to see myself as the person I am today and who I love to be. It’s only through education that we can really start to challenge and question those stereotypes.”

***

#12: Brad Therrien

Brad Therrien had no idea what he was signing up for when he decided to volunteer for the Okanagan Pride Society.

“I didn’t realize I was stepping into a board position; I thought I was just going to be a volunteer,” he says, nearly two years later.

Therrien first served as the group’s treasurer before becoming vice-president in January.

Besides helping to coordinate this year’s Okanagan Pride Festival, until recently the 27-year-old also ran the society’s weekly non-profit bar.

Last spring, Therrien created the Etcetera Kelowna youth program, a weekly after-school space for gay and allied youth aged 15 to 25. The group hosted its first youth-diversity prom in June.

“The idea behind the name is to de-emphasize labels,” he says.

Before launching Etcetera, he consulted with local law enforcement, mental-health professionals and the school district, all of whom agreed that the program was desperately needed.

With the recent closure of Kelowna’s Pride Centre in July, Therrien is now searching for a new location to host the youth group. “There are a lot of kids who do drop out of high school, there are a lot of bullying issues, and we don’t have [programs like] Out in Schools in the area,” he says.

“The [gay-straight alliances] were struggling, and I decided that the best way to help would be to create a safe space for these youth.”

***

#11: Pussy Liquor

“I saw a need and I just kind of jumped in and decided to start doing something about it.”

Pussy Liquor was flipping through the Pride Guide looking for events for her and her friends to attend two years ago when she noticed a gap.

“What I found instead was that all the parties were broken down by binary gender category. There were either men’s events or women’s events but nothing really in between or outside of that, so I felt like something was missing,” the 29-year-old says.

“A lot of my friends fall outside of the categories of gender of man or woman: they identify as trans or genderqueer or androgynous.”

Last year, Liquor launched Genderfest, an all-genders East Vancouver festival held during Pride Week. This Pride, the festival entered its second year, expanding to six events over 11 days, including a one-day conference of workshops and presentations.

The conference organizers received some backlash on Facebook this spring, after some community members noticed that none of the presenters or panellists identified as trans women. Liquor says that kind of criticism is a reality of activism and community organizing and that it is actually a positive thing.

“Although it can be really challenging at times, I do also find it really exciting,” she says. “It means that people are engaged, it means that people care, and it means that people are invested in what’s happening.”

She says it’s important to not just listen to critics, but to actually hear them and follow up and take action.

Liquor has committed herself to producing the festival for one more year before she moves on to other projects.

“I would really like for the community to get invested in Genderfest, to take it on, to give it a life of its own.”

***

10: Cory Oskam

Cory Oskam still isn’t sure what to make of the idea that people look to him as a role model.

“I mean, I’m only 16 . . . As cool as that is, I think there’s definitely more I can do in the community to help others,” he says.

Key to that is following his personal motto: “Be yourself and change the world.” He stresses that his story isn’t unique; he’s just been given the opportunity to help educate others.

“There’s so many other people who could have probably taken my position in expressing transgender issues here in BC,” he says.

Earlier this year, the Vancouver high school student and hockey player met his hero, former Canucks goalie Cory Schneider, and was inadvertently outed to his teammates as transgender by an article posted on the Canucks website.

The teen was then thrust into the spotlight after his story caught the eye of local media.

Oskam is still adapting to the attention and hopes to make the most of it. He was a keynote speaker at this year’s International Day Against Homophobia Breakfast in Vancouver, and he wants to help facilitate more workshops about gender issues with the Vancouver School Board.

“So many people don’t understand what transgender is,” he says. As part of his workshop, he shows a documentary that was filmed when he was 12 and waits for students to react.

“They put one and one together and then they realize that ‘Oh my god, I’ve been talking to someone who’s transgender.’”

Oskam wants to use his experience and his voice to help make sports more accepting and open.

“I really want LGBTQ youth to play the sports they want to, in or out of school. I know so many people who are so scared to play sports because they think that no one will accept them for who they are,” he says.

He’s not sure what his future after high school holds, but he sees a need for more gender therapists, pointing to the long waiting lists for people who are gender-questioning. And, of course, he has no intention of unlacing his skates anytime soon.

“Hockey is my life.”

***

#9: Shaun Hunter-Mclean

A lot has changed in Smithers, BC, since 2011, when Shaun Hunter-Mclean moved to the rural town to finish high school at the age of 17.

Earlier this year, the Bulkley Valley school district amended its anti-discrimination policy to specifically address gender and sexual orientation.

It was a huge victory for the students who are part of the gay-straight alliance at Smithers Secondary and for Hunter-Mclean, who now attends Concordia University in Montreal.

Hunter-Mclean, who prefers the gender-neutral pronoun they, experienced a culture shock when transitioning from the open acceptance of gay culture at a fine-arts high school in Metro Vancouver to the blatant homophobia they encountered in the hallways of a rural secondary school.

Back in Smithers for the summer, Hunter-Mclean noticed other things are changing as well.

“There are a lot more out individuals — not just in the school, but in the community,” they say. “The GSA is continuing to grow as well and is becoming more involved in the community.”

Also a singer/songwriter, Hunter-Mclean spent part of the summer performing at local music festivals.

“I decided to perform in full drag,” says the 19-year-old, whose outfits were part country, part biker. “My goal is to soften the edges around the concept of talking about sexuality and gender.”

“People [in Smithers] are okay with accepting people for who they are, even if they don’t fully understand their identities,” they say.

“You don’t hear people talking about it — it’s still sort of an awkward subject — so now it’s a matter of getting people more comfortable and getting over that fear of understanding.”

***

#8: Isabel Krupp

Isabel Krupp blames her East Vancouver upbringing for her activist spirit.

“I was really lucky growing up to have an amazing queer mentor in my life,” the 23-year-old says. “As a young person, I think it’s important to have those intergenerational connections.”

Krupp works at two local non-profits: as a program and office administrator at Check Your Head, which empowers youth to take action for social, economic and environmental justice; and as youth program coordinator at West Coast LEAF, a group that uses equality-rights litigation, law reform and public legal education to fight discrimination against women.

This past summer, she was a cabin leader at CampOUT, and in her spare time she facilitates workshops on HIV 101 and sexual well-being for YouthCO.

Having grown up in a poor working-class and activist community, she says she’s found it impossible to distinguish between her sexual identity and her politics.

“I’m not just a queer person or I’m not just a lesbian; I’m also poverty-class or I’m white or I’m able-bodied — like there’s all of these things that shape how I live life as a queer person,” she says.

Those politics have also led her to get involved in grassroots organizing as part of the Vancouver chapter of Queers Against Israeli Apartheid (QuAIA).

“I think it’s important as queers, as trans people and as allies to be aware of how our movement and culture is being used to push down other groups — if it’s to be used as pinkwashing.”

Last summer, QuAIA members handed out flyers at the Vancouver Queer Film Festival and participated in a successful panel to challenge the inclusion of Israeli government-backed films in the festival. Recently, they’ve been connecting with chapters in other cities and are trying to grow and figure out what to do next.

Krupp points to the spread of pinkwashing of businesses and politicians as a growing problem for the community.

“The idea that tar sands is ethical oil because it’s not coming from the Middle East and is therefore queer-friendly oil is problematic,” she explains. “More and more groups who have had detrimental effects on the queer community will put up a rainbow or come to Pride to put on a veneer of progressive politics, when they’re still doing other things that hurt [us].”

***

#7: Carven Li

Carven Li’s path to the queer community started with looking for a good place to dance.

“Through looking at dance parties, I learned about social-justice issues, and I learned about why I enjoyed some dances more than others,” says Li, who uses the gender-neutral pronoun they.

“I found out that the dances I really had the most fun in, and felt the most safe in, were the most inclusive — they removed financial, physical and cultural barriers,” they say.

Li now sits on the board of Our City of Colours, which has produced a series of culturally and linguistically diverse posters to share queer lives with minority communities in their mother tongues.

A long-time resident of Richmond, the 23-year-old is also working to make the Vancouver suburb a more welcoming space for queer youth.

“Richmond has a huge immigrant population, and it lacks a lot of LGBTQ resources,” they say.

Li is frustrated that the Richmond School District still doesn’t have an anti-homophobia policy in place. They say the lack of clear direction from the top makes some principals reluctant to invite queer non-profits and workshops into Richmond schools.

“It’s very disappointing that the school trustees have not represented the students’ interest by having a queer-friendly policy.”

Li hopes to work with the City of Richmond to create drop-in programs for gay youth and for young people of colour.

A member of the QTIPOCalypse collective for queer or trans indigenous people or people of colour, Li also had the opportunity this summer to be a cabin leader at CampOUT.

“After going to CampOUT, it made me feel that being a youth educator is really rewarding. I was able to see myself in others.”

***

#6: Ander Gates

Ander Gates chose his graduation ceremony to come out publicly to his classmates and to the village of Masset in Haida Gwaii, BC, population 864.

“In a small town, everyone comes to graduation,” the trans man explains. He wore a suit to accept an LGBT bursary offered by two local openly queer nurses. He had applied thinking that since there were only 20 people in his class, his odds of winning were high.

“I wore a suit and I stood in the back row with the boys. There was a front row with girls in dresses.”

Though some students gave him a hard time and objected that he was “ruining graduation,” his teachers were very supportive.

Through the application process, his parents and some of his teachers became aware that he was questioning his gender, although most of his classmates were clueless.

“I started going to school dressed as a boy sometimes,” he says, laughing. “People just thought I was having a sloppy day. They didn’t understand what it was.”

More than his detractors, Gates remembers his cheerleaders and says the support he received has motivated him to give back and support other youth and the queer and trans community.

The 24-year-old now organizes cabarets featuring drag, dance, burlesque, music and poetry every few months at the Purple Thistle, a youth-driven arts and activism centre on Commercial Drive.

“They’re a space for youth to see and perform drag. Most of the venues where drag and burlesque are performed are spaces where youth can’t go,” he points out. “We support a lot of emerging young drag artists.”

When he’s not creating youth performance spaces, Gates facilitates workshops with Qmunity’s Gab youth program and with Vancouver Coastal Health’s Condomania, a program designed to shape positive attitudes around sexual health.

“We have had lots of workshops where, afterward, a student comes up to us and comes out, or thanks us. It’s rewarding to know that we’re making a difference.”

Three years after moving to Vancouver in 2007, Gates responded to an open call to help organize the Trans and Genderqueer Liberation and Celebration March. He’s been involved with the march ever since.

“We’re kind of a group that doesn’t have a lot of visibility or focus in the larger [Pride] march or in queer organizing in general,” he says.

“It’s also very [do-it-yourself] and anti-corporate. It doesn’t have any banks marching in it. It has more of a political edge.”

***

#5: Paige Frewer

It started with a dare.

Party promoter Paige Frewer was bartending at Lick — the now-defunct Vancouver lesbian bar — in 2007, when she got her first taste of performing in drag.

She had asked a friend to help organize a show for her birthday party at the bar, and many of the enlisted acts were drag kings. Under pressure from the performers, she ended up onstage herself that night and the rest is history.

Frewer, who now regularly performs as Ponyboy, had seen a little bit of drag from her time working at Lick but didn’t know much about it. The success of her fundraiser birthday party led to the creation of Man Up, a monthly drag-king show and queer dance party.

“Suddenly, people seemed excited about drag again,” she says. While helping to promote Man Up, she slowly became a convert herself. “I was in love, and I haven’t turned back since.”

Five and a half years later, Man Up is still going strong and has inspired the spinoff Amateur Hour, a rookie night for drag performers who can compete for a paid slot at upcoming Man Up events, at The Cobalt in East Vancouver.

For Frewer, drag is multifaceted: it’s a form of entertainment, it’s a way to exercise a political voice, and it’s a way to reclaim a sense of identity that mainstream society — and even mainstream gay and lesbian society — may not offer.

“A lot of events in the queer community, and women’s events, seem a little bit more prescriptive to a particular type of gay or a particular type of lesbian, and not everybody feels comfortable in those spaces,” the 27-year-old says.

“What I aim to do with Man Up is to have it be an inclusive space where any kind of gay woman can go — but you’ll also find all kinds of other people as well.”

***

#4: John Kuipers

While many young gays can’t wait to leave the suburbs for queerer neighbourhoods closer to the city, John Kuipers has decided to stand his ground in his community.

Part of Kuipers’s fight started in 2008 when, as president of the Pride society at the University of the Fraser Valley, he co-organized a social-justice rally in Abbotsford, the heart of BC’s Bible Belt, after the school district chose not to offer the Social Justice 12 course in local classrooms.

“It was a real cornerstone to really find out who was an ally and who wasn’t,” he says of their initial effort. “It was the start of people saying that we shouldn’t have to deal with [homophobia] in the Valley. It was a fight, but it was one that we won.”

For nearly six years, Kuipers has also coordinated the Fraser Valley Youth Society (FVYS), which formed in 2006 after Youthquest stopped funding gay youth drop-ins in Abbotsford.

Over the years, FVYS has grown from being a drop-in to also hosting events and spreading awareness about and advocating for queer youth and issues.

This past spring, Kuipers helped lead a team of youth volunteers who organized the first-ever Fraser Valley annual Pride March.

According to Kuipers, while is there still much more to be done, change is coming. More local organizations and businesses are willing to lend their support publicly, he notes.

“It communicates something to the youth,” the 28-year-old says. “There are other people out there that say it’s okay to be gay, that you don’t have to repress that part of who you are and get the hell out of here as soon as you can and go to Vancouver.”

For now, his focus is on training and empowering the next generation of activists to take over and keep up the fight.

“My philosophy, both professionally and personally, is that if you’re going to take on a task, you need to take it from start to finish and do the best job you can,” he says.

“There’s work to be done.”

***

#3: Melanie Matining

When Melanie Matining came out of the closet in university, she came to the startling realization that she was expected to choose which part of herself was more important.

“As a queer woman of colour, I felt there were really big blocks,” she recalls. Then, taking women’s studies at the University of Victoria and working for a non-profit that targets women of colour, she found herself wanting to discuss queerness at work or sexuality with students of colour on campus but was repeatedly met with resistance.

“We all have these multiple layering identities, but we only really seem to talk about one thing. Either we’re going to be women or people of colour or queer. It’s such a shame that all of these conversations are happening in isolation,” she says.

Last year, Matining was one of several Vancouverites who helped found the QTIPOCalypse collective, a group for queer or trans indigenous people or people of colour (QTIPOCs).

“In queer and LGBT spaces in Vancouver, the conversation of race sometimes seems like something that’s a bit too big,” the 26-year-old says.

Since forming last fall, the group has held a showcase for QTIPOC performers, singers and spoken-word artists, a dance party and potlucks.

The group has received some pushback from people who haven’t agreed with their policy of holding events for only self-identified QTIPOCs.

“The whole point of QTIPOC-only space is to listen to the community and ask what they need,” Matining says. “People were saying, ‘Sometimes we feel really in the margins. We’re hanging out in spaces where people don’t want to talk about race, but there’s very blatant racism.’

“We wanted to create a platform for that. This is a really important piece of us and we don’t want to be quiet anymore, but we also want to do it in a way that’s really celebratory and healing. We want to do it in a place that feels safer.”

Matining says that collectives like QTIPOCalypse are only one part of addressing racism and that change also needs to happen within existing groups.

“We just want to be cheerleaders for people.”

***

#2: Dave Deveau

Dave Deveau may divide his time between two worlds — in the theatre, as an award-winning playwright, and in the scene, as an Eastside party promoter and as drag queen Peach Cobblah — but he sees them as intertwined and connected.

“They’re both about building spaces for people who feel like they don’t have any,” the 29-year-old says.

Though his work with his husband’s theatre company, Zee Zee Theatre, has been based heavily on gay themes, he says he isn’t necessarily writing for gay audiences.

“My body of work is pretty darn queer,” he says, laughing. “But I’ve never been of the belief that the queer community are the people who need work about queer issues. I think it’s actually quite the reverse. I think it’s everyone else.”

His critically acclaimed 2011 play My Funny Valentine delves into the murder of teenager Lawrence King, who was shot in the head after he asked another boy to be his Valentine. The production has been mounted in Dublin and returned to Vancouver for a second run last February.

Deveau says audiences often found themselves relating to characters in ways they hadn’t even considered and finding common ground with voices that they wouldn’t ordinarily care to listen to.

“For me, theatre has always been a way to ask questions that I don’t have the specific answers to. It becomes a means to generate conversation or to elicit something in someone that surprises them.”

Deveau is also proud of his work promoting events, including the dress-up party Queer Bash, the drag show Apocalypstick, and the gay hip-hop night Hustla. He and business partner Brandon Gaukel were the first to partner with the owners of The Cobalt to introduce queer programming — three years later, the venue is the de facto Eastside gay bar.

“There’s something really magical about really, really gay space happening in a non-gay community,” he says.

***

#1: Justin Saint

The first time Justin Saint showed up in full costume as Queen Amidala — Natalie Portman’s character from Star Wars — at a fan convention, people weren’t sure what to make of him.

“They didn’t know how to react,” the 24-year-old says. “A lot of people thought I was a girl, and then when I opened my mouth…” he trails off, laughing.

“The second year that I did it, they already knew who I was and they were really excited.”

Since then the self-described hardcore gamer and geek has thrown himself into cosplay (short for costume play), making appearances as Harry Potter’s Lord Voldemort and husband and wife Khal Drogo and Daenerys Targaryen, from Game of Thrones.

Saint is the director of the BC Superfriends, a newly formed group for queer geeks and their allies in the Lower Mainland.

The Superfriends plan to throw three parties each year: at Pride, for Halloween and in the spring. Their mission is to create events where everyone can be their geeky selves, regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation.

Four years ago, Saint also founded and started organizing the Vancouver Gaymers, after running into homophobic behaviour at other board-game meet-ups.

“In the gaming community, there was a lot of discriminatory language going on,” he says. “We needed a safe space.”

The Gaymers now host two monthly meetings: a board-game night and a second night focused on video games.

Saint also helps to raise money for AIDS charities through his alter ego, Sister Sweet Cherribum, a nun with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

“I grew up Catholic with a strong respect for nuns,” he says. “I can continue that tradition in a queer way that makes people smile.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra