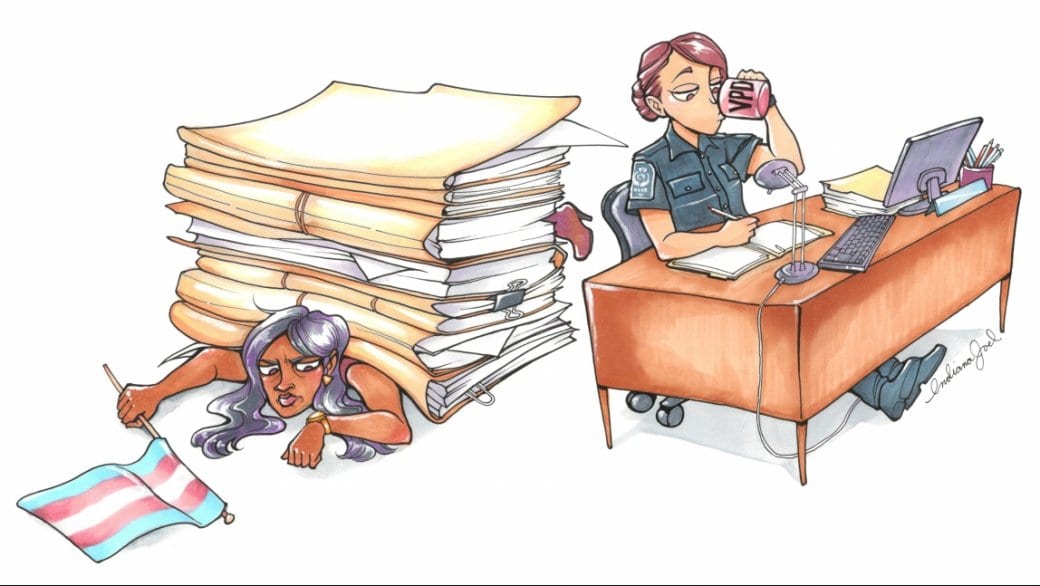

Two years after the Vancouver Police Department was found to have discriminated against trans people, activist Catherine Mateo is frustrated with the lack of action within the VPD.

“The reality is that VPD as a department is behind, and they’ve been behind for years,” Mateo says.

In Dawson vs Vancouver Police Board, the BC Human Rights Tribunal found the VPD had discriminated against Angela Dawson, known in Vancouver as Roller Girl.

According to the 2015 ruling, Dawson alleged six separate incidents of discrimination, and argued that together they demonstrated that the VPD systemically discriminated against trans people.

The tribunal, which heard that Dawson was abused as a child, left home at age 16, has a criminal history and lives with several complex health issues, found that police intentionally misgendered Dawson on several occasions and denied her necessary medical care while in custody.

The most notable incident of discrimination occurred in 2010 when police arrested Dawson and held her in custody overnight for parole violations. This occurred shortly after her gender- confirming surgery. Not only was Dawson misgendered in the police reports, she was also denied necessary post-operation medical care, despite asking both officers and the jail nurse.

In her ruling, tribunal member Catherine McCreary emphasizes that Dawson was “very concerned” about missing her post-surgical care. “It was at the top of her mind. There were serious long-term consequences for non-compliance. She seems to have spoken about it to everyone with whom she came in contact in the jail.”

But her medical needs were not met. In a statement submitted at the hearing, the nurse on staff, Cheung Kwok Sun, consistently referred to Dawson as “he” and explained that he didn’t know whether Dawson was telling the truth about her surgery because she would not allow him to examine her. “Without checking his ‘vagina,’ I did not know whether inmate had a ‘real’ surgery or not,” Cheung says in his statement.

A couple months later, Dawson was held in jail for several hours for a separate incident, and again did not receive necessary care.

The tribunal ruled that by denying post-op medical care on two separate occasions, police discriminated against Dawson on the basis of her gender identity.

The ruling also documents other incidents where officers referred to Dawson as “he” and “she” interchangeably, as well as testimony from one constable on when to respect gender pronouns: “If a person has male genitalia, they are male and, that if they have female genitalia, they are female . . . A person who is born with male genitalia cannot be referred to as female until they have had gender-reassignment surgery.”

In all, the VPD was found to have repeatedly misgendered Dawson during both her stays in the jail, and on one other occasion, each of which amounted to gender-based discrimination.

The tribunal gave the VPD one year to create a policy to “recognize and prevent discrimination” against trans people, and to train its officers to be culturally sensitive to the trans community.

That was in March 2015.

The chair of the Trans Alliance Society, Morgane Oger, followed the Dawson versus Vancouver Police Board ruling and the VPD’s progress in implementing it. During her time as a member of the LGBTQ+ advisory committee for the City of Vancouver, Oger formed a subcommittee with the sole purpose of ensuring the ruling was implemented.

The VPD had until March 24, 2016, to make the changes. However, according to Oger, the VPD’s draft “initial contact” policy was insufficient and prepared without consulting the community it was meant to serve.

The VPD “were prepared to hand in a policy document that did not meet the standards of the community,” Oger alleges.

According to Oger, when the subcommittee finally managed to meet with the VPD to discuss its draft, it was close to the one-year policy change deadline.

“We came to an arrangement in which we agreed that the LGBTQ+ advisory [sub]committee would have the opportunity to assist with the rewriting of the policy they were putting forward to make it more sensitive and more compliant with the expectations of the transgender communities,” she says.

“The finished product is much, much better than what was originally proposed,” she says, referring to the VPD’s “initial contact” policy passed in June 2016. The policy instructs officers to refer to trans and non-binary people by their chosen name and pronoun.

And the VPD did provide training to its officers on time, Oger adds, noting that police brought in organizations to help with “significant amounts of training” and launched a video last June.

But two other related policies — on how to transport and hold trans people in police custody, and on a person’s right to have an officer of the same gender conduct a body search — still need work, Oger says.

Though the tribunal did not specifically name which policies the VPD needed to change, Oger says she and the advisory subcommittee identified these two policies when they began working on the first policy.

When Oger was first interviewed for this story in April, she said she’d received an email from someone at the VPD saying the two remaining policies were set for implementation by the end of May.

On May 31, Oger told Xtra the VPD would miss its promised deadline.

“These policies were written and finalized by the group some months ago now, and you know our understanding was that it was simply a matter of going through the process and getting them done. But they’ve decided to make more changes,” she says.

VPD spokesperson Sergeant Randy Fincham doesn’t know when the search policy will be finalized.

When asked about the delay on May 18, Fincham suggests the search policy’s lateness is the result of how closely the VPD is listening to community groups and stakeholders. He did not specify which groups were consulted.

“We continue to work with a number of community groups to make sure their interests are represented,” he told Xtra by phone. “We will take the time that it needs to make sure that is done professionally, correctly and properly,” he continued, later adding that “unfortunately that does take time to listen to the concerns of the community and make sure there aren’t any community groups left out of that consultation.”

Fincham also provided some details on the trans sensitivity training for VPD officers.

“We have a number of ongoing training initiatives in the VPD specific to the transgender community. We are actually just finishing up three of the last training initiatives with our staff, cultural awareness sessions with our police department, where we have members of the transgender community coming in and speaking with our officers,” he says.

Xtra asked for copies of any handouts that officers may have been provided with, or documents from the presentations, but Fincham said he was unable to send any documents. Instead he referred Xtra to the VPD’s “Walk with Me” training video.

Xtra spoke with Angela Dawson about the tribunal ruling and her experiences of the police since. She says she wasn’t contacted about the policy. She says she still doesn’t feel safe around police and that some of the personal information revealed in the ruling has actually made her feel more vulnerable.

The Vancouver Police Department’s training video, “Walk With Me,” was released June 16, 2016.

VPDtv/Youtube

Trans activist Catherine Mateo alleges the VPD’s lateness in implementing its new trans policies is part of a larger pattern of inaction and delays by the VPD.

Mateo has researched the VPD’s trans-specific policies and has read the 57-page Dawson ruling. What she learned from reading the case surprised her.

A close reading of the the ruling reveals that in the years before the incidents of discrimination against Dawson, the VPD had intended to implement trans-inclusive policies but failed to do so. In fact, the VPD had engaged in community consultations on how to interact with different segments of the LGBT community, and published its findings in a 2008 report called “The Aaron Webster Anti-violence Project,” named for the man fatally gaybashed in Stanley Park in 2001.

The consultation process and report were the product of a partnership between the VPD and Qmunity (then The Centre) which received special funding from the BC Ministry of Public Safety and the solicitor general’s safe streets and schools initiative. The project’s stated goal was to strengthen relationships between the VPD and LGBT communities to address the fact that LGBT communities under-report both hate crimes and spousal violence.

The recommendations that emerged from the consultation focused on providing more outreach and support to LGBT people subjected to violence, and on training officers on how to interact respectfully with trans, two-spirit and queer people of colour. The recommendations also encouraged the VPD to keep these communities updated on the LGBT-specific trainings it would provide to its officers.

But after the report was released, the VPD didn’t implement its own recommendations, something it readily admitted to the Human Rights Tribunal during the Dawson hearing.

In her ruling, tribunal member Catherine McCreary writes: “Inspector de Haas testified that none of these recommendations have been implemented. . . . It seems to me that the VPB [Vancouver Police Board] has virtually no policies or training of officers on how to appropriately deal with trans people without discrimination.”

Xtra asked Sergeant Fincham about the VPD’s failure to comply with the Aaron Webster report’s recommendations, and why the force didn’t provide any trans-sensitivity training to its officers between 2008 and 2015. He said he could look into the matter further. “When you’re looking at recommendations to provide training through an agency as large as the VPD, you know it does take time to work with the community, consult with the community, develop and deliver training that meet the needs with the community,” he said.

Mateo was disappointed to learn that the Aaron Webster report was not implemented, and that the Dawson ruling hasn’t been fully implemented either.

“Community and the police at some point need to have a healthy relationship and I think that’s the goal that everyone should be pushing for,” she says.

“But when you have the police department spending a great deal of resources in obtaining this [2008 Aaron Webster] report and obtaining a partnership with community and a whole bunch of other organizations and then kind of just ignoring everything — it sucks.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra