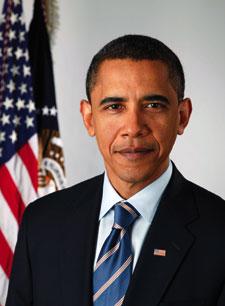

Eleven years after Matthew Shepard was brutally gaybashed, tied to a fence and left to die in Laramie, Wyoming, US President Barack Obama signed off on hate crime legislation bearing his name Oct 28.

The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr Hate Crimes Prevention Act expands upon a 1969 federal hate crime law (covering crimes motivated by someone’s race, colour, religion or national origin) to include crimes motivated by a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity or disability.

Shepard was a gay University of Wyoming student. Byrd, a black man, was dragged to death behind a pickup truck in Texas in 1998, the same year Shepard was murdered.

The legislation, which passed as an amendment to a defense department appropriations bill, grants federal authorities greater latitude to pursue hate crime investigations and prosecutions, and to assist state and local jurisdictions in such investigations.

It also provides financial support to state and local authorities to offset the costs of investigating and prosecuting hate crimes.

Vancouver defense lawyer Garth Barriere notes that the new American legislation actually creates a hate crime offense. In Canada, hate motivation is only considered at sentencing.

Does a hate crime “deserve its own offense?” Barriere wonders. “I guess the advantage of it is the labelling,” he offers.

“There might be some value in that — not in terms of the amount of people who are going to be prosecuted or sentenced, or the length of sentencing — but just in terms of the value in actually calling the offence a hate crime as opposed to saying it’s a crime with a hate motivation.”

Naming the offense can send the message that society won’t tolerate such offences, or thinks those kinds of offences are particularly deplorable, Barriere explains.

Yet as a defense lawyer, he says he’s always found it difficult to measure one violent crime as more serious than another.

“Is a crime motivated by hate worse than a crime motivated by nothing at all if the two people suffer the same physical injuries? What does it matter what it was motivated by, and is one victim less worthy than the other?” Barriere asks.

“I think there is an argument, to say that a violent crime motivated by hate is not any better or worse than any other crime, but [that] it’s distinct and it deserves its own distinct response.”

In comments to gay journalist Rex Wockner, gay writer and blogger Andrew Sullivan says under the hate crimes rubric, gays are asked to see themselves as “sad, passive victims of hate, reaching out to government to protect them more than those just targeted for other reasons.”

But Barriere says this isn’t about gay people choosing to be victims. “It’s the criminal who says, ‘I choose you to bash because you’re gay, or because I think you’re gay,’” he points out. “It’s not like we’re victimizing ourselves simply by having the law.”

Part of the preamble to the new US legislation states that violent crime motivated by bias not only devastates the actual victim but “frequently savages the community sharing the traits that caused the victim to be selected,” Barriere points out.

BC Civil Liberties Association executive director David Eby says he understands the perspective of calling a hate crime by its name from the outset, but doesn’t see how that would change anything, except give the prosecutor one more element to prove in order to get a successful prosecution — proving the hate in addition to proving the assault.

“It’s hard to know what the effect of that would be except for the fact that it would be on the person’s criminal record, so it might affect their getting a job, or an employer might see it as worse that they had been convicted of a hate crime as opposed to just a regular crime, or the sentence might be worse, but actually under Canadian law the sentence is already dealt with,” Eby says.

The main benefit of having a specific hate crime from the beginning, he says, is that the affected community would feel that the “particular and different quality of the attack” was being acknowledged.

What is particularly interesting about the American legislation, Eby says, is the dedicated funding from the federal government to investigate and prosecute hate crimes.

That’s something Canada’s gay community should look into: pushing different levels of government to provide financial incentives to authorities to aggressively investigate and prosecute hate-motivated crimes, he suggests.

“There’s so much money to investigate and prosecute pointless and victimless crimes, like drug crimes. Surely there’s some room for government to dedicate money to the investigation of crimes that affect the participation of whole segments of society in our larger democracy,” Eby says.

Barriere agrees.

At the end of the day, the effectiveness of legislation depends on how much is done to back it up, he says.

“I think the keeping of statistics is valuable because it makes the problem more visible,” Barriere adds when asked if better statistical records of hate crimes would also be helpful to address such offenses.

The more these crimes are documented, the more attention gets paid to them and the more resources get directed to them, he says.

But statistics only go so far, he adds.

The question the gay community legitimately keeps asking is whether the police and Crown prosecutors are sufficiently motivated to investigate and prosecute hate-motivated gaybashings, Barriere says.

“I don’t think they’re motivated enough, or perceive the cases in the same way as we would,” Barriere says. “But mandating someone to be motivated, I don’t know. They either are, or they aren’t, not because they’re ordered to by a law.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra