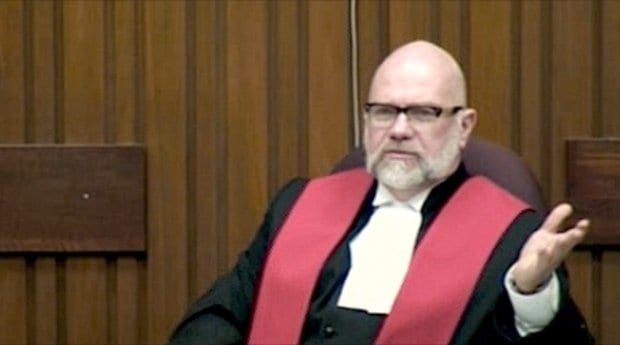

The decision in Trinity Western University’s lawsuit against the Nova Scotia Barristers Society will have national importance for law in Canada, Nova Scotia Supreme Court Justice Jamie Campbell said Dec 19.

“This is not just a matter between two parties, but a matter that is of fundamental importance to our legal system,” he said in response to testimony from the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission.

Campbell was presiding over the fourth and final day of a hearing on whether the Nova Scotia Barristers Society (NSBS) can block TWU graduates from articling in Nova Scotia.

The NSBS ban is aimed at TWU’s community covenant, a document all students must sign that forbids sex outside of heterosexual marriage. The NSBS decided in April it would ban TWU students from its bar admission program unless the BC university dropped or changed the covenant. The university took the society to court, arguing that the ban amounts to religious discrimination.

To reach a decision, Campbell will have to balance TWU’s right to religious freedom against the rights of queer people in Nova Scotia who do not want to have a policy they see as discriminatory validated by the province’s bar association. “To grossly simplify,” Campbell said, the case is about queer people who would be offended to see the covenant validated, and on the other side “a law school student being able to look at his neighbour in torts class and say, ‘Well, at least I know he’s not having gay sex.’”

Campbell indicated he would give his ruling within the first couple months of the new year.

Lawyers from both sides presented final arguments on the case. NSBS lawyer Peter Rogers called TWU a “rogue law school” and continued to compare it to all-white schools in the United States. “[TWU lawyer Brian] Casey and his intervenor colleagues are, in my respectful opinion, upholding a separate-but-equal system of education,” he said. “If we validate Trinity Western University’s law application, we validate homophobia, and the message to LGB youth is that they do not matter.”

Justice Campbell pushed back when Rogers said that the university would not lose any meaningful religious rights if they got rid of the covenant. “They’re saying that Christian education means an education where you’re surrounded by, if not other evangelical Christians, at least people who follow basic evangelical Christian rules,” Campbell said. “You’re saying, ‘That’s not important.’ It’s not important to you, but it seems pretty important to them.”

Casey argued a similar line, accusing the NSBS of overstepping their bounds and disregarding some rights on behalf of others. “I might want to reduce poverty as much as I can, but I can’t use someone else’s money to do that,” he said. “I might want to protect sexual minority interests in Canada, but I can’t use someone else’s rights to do that.”

Casey said a decision like this one is too delicate to be left in the hands of a vote by the NSBS council. “The whole thing about minority rights is that they only affect a minority of people,” he told the court. “We can’t decide them by taking a vote.”

The court also heard from Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission lawyer Lisa Teryl, who said the TWU covenant was actually bad for evangelicals in Canada. She argued that if the university forces students to sign the covenant, it makes it more difficult to protect their religious rights under the Charter. “Evangelical Christians are in the same boat as every other constitutionally protected group, and if that boat springs a leak, it affects everyone,” she said.

Whether or not the Nova Scotia decision matters hinges on TWU’s accreditation as a law school in BC. Earlier in December, BC’s former minister of advanced education pulled his approval of the law school after a vote by the Law Society of British Columbia.

TWU announced Dec 18 that it is suing the law society over that decision.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra