On Dec. 1, 2020, the High Court of England and Wales made a stunning ruling that would change the lives of trans youth across the country: Trans kids under 16, the court ruled, were “unlikely” to be able to give informed consent to receiving puberty blockers.

The case was brought to the court in 2020 by a psychiatric nurse who worked with those seeking transition-related health care. But she later passed the torch to Keira Bell, a 23-year-old woman who started taking puberty blockers at 16. Bell was prescribed testosterone at 17 and had top surgery a few years later before realizing she wasn’t trans. She claims she’s been left with irreversible physical changes to her body—something she feels was not informed about by health care providers. Bell and her co-claimant, the mother of an autistic trans teen who believes her child isn’t really trans, were represented in court by Paul Conrathe—a lawyer who is anti-abortion, opposed equalizing the age of consent for homosexual sex and has connections to conservative U.S. hate group Alliance Defending Freedom.

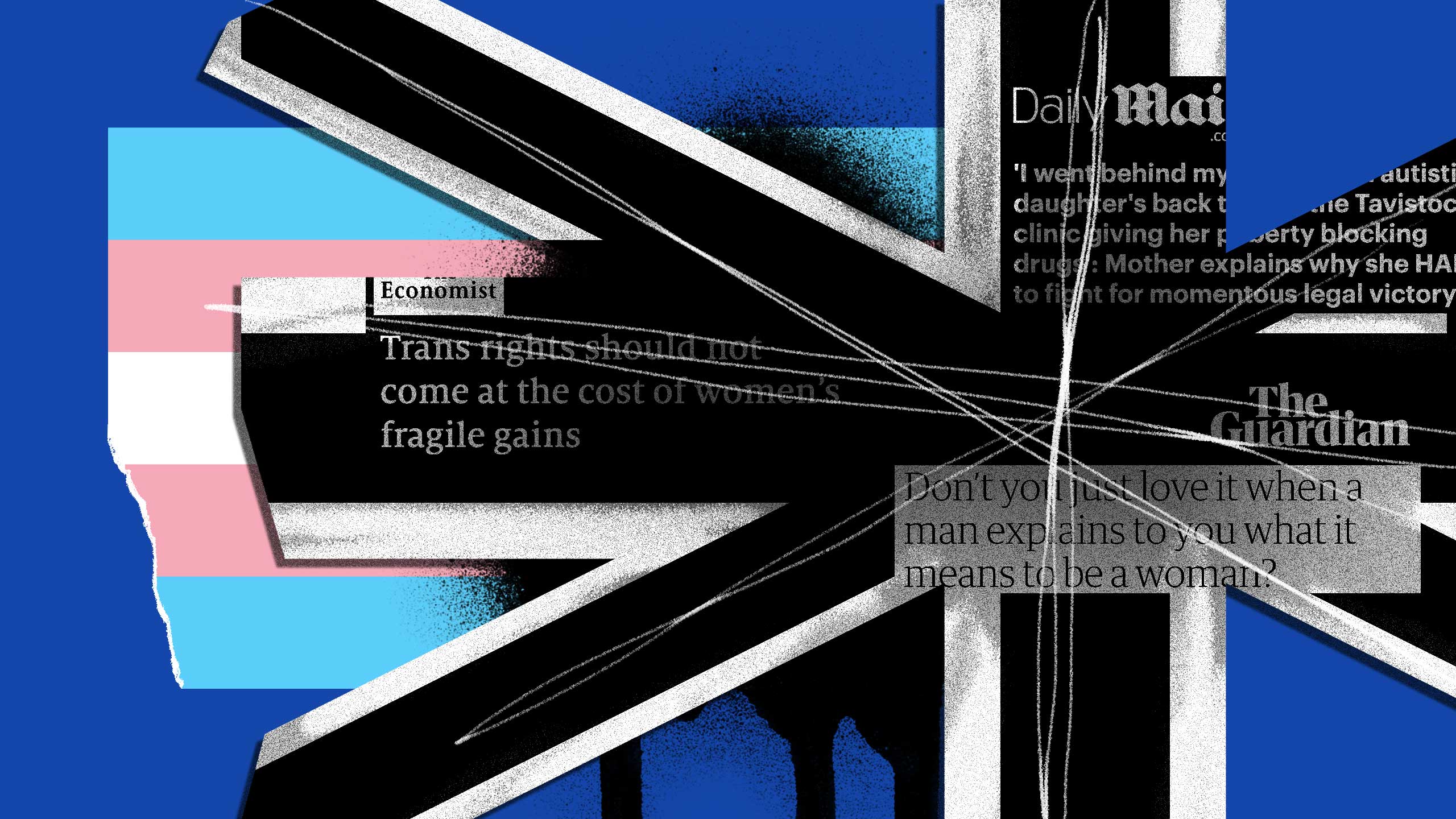

In the ensuing case, Bell v. Tavistock (of Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, England’s only youth gender clinic), the court sided last month with the claimants—even if it put the U.K. at odds with international trans health care guidelines. While trans folks and allies lamented what the ruling would mean for trans and non-binary youth in the country, the U.K.’s press pundits seemed elated: The centrist Economist celebrated the court ruling as a policy other countries should learn from; the soft-left Observer said it would “halt a disturbing trend”; the right-wing tabloid Daily Mail called it “a long-awaited victory for common sense.”

Across the political spectrum, the U.K. media perpetuated a common refrain: That we should be concerned about trans children and that the hypothetical harm of giving a cisgender child puberty blockers is worse than the actual harm of forcing a trans child to go through a puberty that they know is wrong. Cloaked in a language of worry and protection, these transphobic takes don’t suggest that youth can’t be trans—rather, that children cannot know they’re trans.

Unlike in America, where transphobia is frequently connected to right-wing beliefs, transphobia in the U.K. is often tied to feminism—TERF, a common descriptor, stands for “trans-exclusionary radical feminist” (though many proponents aren’t particularly radical, or feminist). This brand of transphobia takes up cases like Keira Bell’s to argue that trans people harm women: That trans men, who aren’t really men, are confused lesbians who have fallen victim to internalized misogyny and homophobia, and their transition betrays their true gender and sexuality. Trans women, who aren’t really women, are invading women’s spaces to prey on them, victimize them or try to force lesbians to sleep with them; and even if trans women aren’t dangerous, men will pretend to be trans women and do all these things. Non-binary people, in this worldview, simply don’t exist, because there are only two genders, and refusing to identify as either one harms gender nonconforming cis people (especially butch lesbians).

The media reaction to Bell v. Tavistock is just one recent example of longstanding and unique TERF rhetoric in Britain. In 2020 alone, TERFism was abundant: The same day the U.K. High Court made its ruling, Lush, a cosmetics company known for its progressive charity campaigns, admitted they had donated £3,000 (the equivalent of more than C$5,000) to anti-trans group Woman’s Place UK. Later that month, broadsheet newspaper The Telegraph published a story stating lesbians faced “extinction” from trans people. The article extensively quotes the LGB Alliance, a group representing lesbian, bisexual and gay people who are opposed to trans rights. And we can’t forget our favourite British children’s author, who doubled down on her TERF-y beliefs with her latest release (under her male pen name, no less).

There’s no simple reason for why TERFs are so abundant among Brits; rather, a culmination of factors appear at play. Some point to the antiquated ideologies of a generation of journalists and publishers who have dominated the mainstream media. Others say it’s intrinsically linked to political leaders who have failed to denounce hate. No matter its origins, this rampant transphobia has become a nation’s accepted bigotry. Other divisions aside, no rhetoric seems to unite the British left and right quite like transphobia.

TERFs are not a new phenomenon. The term “TERF” has been around since 2008, when it was coined by cisgender feminist Viv Smythe as a “deliberately technically neutral” way to describe feminists who excluded trans women from their ideologies. It’s not clear how the term gained prominence; in 2012, “RadFem” was the most commonly used shorthand for trans-exclusionary radical feminists, with TERF gaining prominence in 2013 and onwards.

But the overarching idea that trans women are not women and do not belong in women’s spaces dates back to at least the 1970s. The logic is rooted in the concept that, because cisgender women experience sexism perpetrated by men, trans women—who are assigned male at birth—are therefore oppressors rather than fellow victims of the patriarchy.

In the decades since, a number of high-profile feminist commentators in the U.K. appear to have internalized parts of this rhetoric. Sheila Jeffreys, a prominent TERF in the ’70s, penned a 2012 op-ed in The Guardian (traditionally Britain’s most progressive major newspaper) to defend her opposition to “transgenderism.” She told the U.K. Parliament during a 2018 presentation at the House of Commons that trans women are “parasites.” In 1989, The Female Eunuch author Germaine Greer called a trans woman “a gross parody of my sex.” Meanwhile, writer Julie Bindel started penning transphobic pieces in The Guardian in 2003, including one about a trans woman called Claudia who, not unlike Keira Bell, regretted having surgery. (“It’s always Claudia you trot out,” noted a trans activist in 2009. Bindel was still trotting her out in 2020.) As trans writer Shon Faye points out, Greer was once “a staple of British public life” whose name has been a short-hand for feminism; her cruelty toward trans people became accepted by some feminists as dogma. Even today, Greer and Bindel continue to appear in British national media.

“As trans folks become more visible in the U.K., so too does a new brand of anti-trans rhetoric that positions trans rights as a complication of women’s rights.”

While TERFs have historically focused on the dangers trans women present to cis women, the last couple of years has seen increased discussion around trans men, too—painting them as confused, responsible for the disappearance of lesbians or infected by a social contagion. Note the dichotomy: Trans women (“really men”) use the patriarchy to victimize women, while trans men (“really women”) are victims of the patriarchy.

As trans folks become more visible in the U.K. and around the world, so too does a new, particular brand of anti-trans rhetoric—one that positions trans rights as a complication of women’s rights more generally. Ruth Pearce, an academic who primarily focuses on trans health research and recently co-edited the anthology TERF Wars: Feminism and the fight for transgender futures, dates this modern wave of transphobia to around 2017. For Brits in particular, she traces it to three specific causes: Existing transphobia in feminist circles, recent right-wing sentiment that’s anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-women, and the British government’s consultation into reforming the Gender Recognition Act.

It’s hard to avoid this rhetoric: Research commissioned by the U.K.’s press regulator concluded trans news stores have grown 400 percent since 2010 and have become more “strident” and “heated.” Linguist Paul Baker’s research finds a slightly more conservative, yet no less concerning estimation: He calculated that between 2012 and 2019, the number of British news stories about trans topics increased by 250 percent. While Baker found the proportion of anti-trans coverage remained similar, more media reporting means there’s quantifiably more negative stories than there were a decade ago.

“Anti-trans groups get incredible amount of space in public discourse and the media,” Owl Fisher, a non-binary journalist and trans rights campaigner, says.

Media in the U.K. has long been white, wealthy and interconnected, and it’s within these circles especially that transphobia has “become very fashionable,” Jane Fae says. The chair of Trans Media Watch, a charity that advocates for better press coverage, Fae points to Ian Katz as an example: During his stints at the Guardian newspaper, BBC and Channel 4, each publication saw a rise in transphobic coverage. Katz is married to Justine Roberts, founder and CEO of Mumsnet, a website that’s become a hotbed of British TERFs. As writer Laurie Penny explains, “The ecosystem of liberal media and left-wing activism is smaller and more quarrelsome in Britain than it is in America, and a lot of people know each other, and a lot of [transphobia in media] comes down to in-group loyalty and personal drama.”

Consider Suzanne Moore writing in the centre-left New Statesman in 2013, where she made a derogatory comment about women being expected to have bodies like “a Brazilian transsexual.” Moore was widely criticized for her comments—leading to fellow writer Julie Burchill defending her friend in The Observer by calling trans women “screaming mimis” and “bed-wetters in bad wigs.” The op-ed was so offensive it was taken down.

“Uniting left and right, that brand of transphobia eventually made its way into the British House of Commons.”

British TERFs also had a moment in 2015, when students at universities across the U.K. started “no-platforming” problematic speakers—arguing that they shouldn’t be allowed on campus to spread hateful views and that their presence made students feel unsafe. This included both right-wing provocateurs like Milo Yiannopoulos and TERFs like Germaine Greer. Many people were not actually no-platformed, but speakers insisted they were being censored. Newspaper columnists sprang to their defence, insisting TERFs have a right to be invited for free-speech reasons or debated to be proved wrong. It solidified sympathy for TERFs across political lines, as many banded together in a united fight against the perceived threat of “loony left” students.

The free-speech defence is also a favourite of both the left and the right. Some liberals hold up free speech as a civil liberty and classify no-platforming as censorship, particularly of cis women (the counter-argument being that the right to speak and the right to an audience are different things). Conservatives, meanwhile, use free speech to assert the right to be offensive without consequence.

Uniting left and right, that brand of transphobia eventually made its way into the British House of Commons.

Looking back at the past few years of British (Conservative-led) government, it’s easy to chart the decline in trans inclusion with the change in leaders. In 2016, the Women and Equalities Committee for Prime Minister David Cameron released a report that recommended dozens of progressive reforms, such as legally recognizing non-binary identities, making it easier to legally change your gender, lowering the age of legal recogntition to 16 and improving access to medical transition services. Under PM Theresa May just two years later, there was a marked shift: 2018 Women and Equalities Minister Penny Mourdaunt said “trans people need to be supported” but promised to listen to “women’s groups in particular.” By 2020, Boris Johnson’s Equalities Minister Liz Truss praised the conservative, anti-trans Heritage Foundation and lied about meetings with trans groups.

But perhaps the greatest example of Britain’s burgeoning anti-trans rhetoric took place in 2017. Ahead of a general election, May’s government announced a public consultation into reforming the 2004 Gender Recognition Act (GRA), the legislation that lets trans people legally change the gender on their birth or adoption certificate. The consultation, which was open to the general public, looked to gauge public opinion on whether the GRA should be reformed or updated.

Currently, the GRA stipulates that to obtain a Gender Recognition Certificate (or GRC, the piece of paper that changes the sex marker on your birth or adoption certificate), trans adults have to provide extensive medical history, proof of living as their gender for at least two years, a sworn declaration to live in that gender forever and a fee of £140 (about C$240). A GRC can then be used for marriages, state pensions and death certificates.Trans campaigners hoped the U.K., like neighbouring Ireland, might be moving to a self-ID model, where trans people don’t have to provide medical evidence of being trans.

While Ruth Pearce notes that, at the time, reforms were supported by all major political parties, she says the consultation was a ploy to appease “the more left-wing elements of the Conservative support base while not actually making any massive changes to people’s lives.” Instead, the announcement of the GRA consultation was enough to trigger a powder keg of transphobia: Op-eds were vehement in their opposition. Advocacy groups sprung up and mobilized to protest trans inclusion. And more than one-third of all British trans folks experienced a hate crime in that year alone, quadrupling over a five-year period.

“In 2017 alone, more than one-third of all British trans folks experienced a hate crime; that rate quadrupled over a five-year period.”

The GRA consultation “just opened up this massive slew of opposition, to trans women in particular,” says Susie Green, CEO of Mermaids, a charity dedicated to supporting trans children and their families. (Green is cisgender, but her daughter came out as trans in 1999 at age six.)

Green isn’t alone in considering the consultation a turning point: In TERF Wars, the editors (including Pearce) note that “a significant upsurge in public anti-trans sentiment [has taken] place since 2017, when Prime Minister May announced the Conservative government’s plan to reform the Gender Recognition Act.” Non-binary filmmaker and activist (and Owl Fisher’s partner) Fox Fisher adds, “Ever since the government announced that they were reforming the Gender Recognition Act… it has become a vehicle for transphobia and incredibly hostile attitudes.”

Much of the problem was timing. The public consultation was announced in 2017, but didn’t launch until 2018. “It was like this information vacuum, where people could start pouring concerns and worries and misinformation,” Pearce says. “There was this year during which you could have all this misinformation circulate.”

That misinformation included how TERFs portrayed the GRA. Many returned to their familiar talking points, arguing that reforms would allow predatory men easier access to abuse cis women—in public bathrooms, in gender-segregated prisoners, even in sport. Much of the argument was actually unrelated to the GRA: Single-sex spaces are actually governed by Britain’s Equalities Act of 2010. That didn’t matter; the GRA provided a timely hook, allowing for open fear mongering about trans people.

That interim year saw high-profile feminist writers like Hadley Freeman, Sarah Ditum and Helen Lewis produce more TERF-related articles. The Times of London, a traditionally centrist paper, went hard on intolerance, publishing more transphobic op-eds than ever before, and letting a journalist devote herself to writing constant transphobic coverage. Conservative outlets like The Telegraph and The Spectator saw trans rights as, according to trans writer Juliet Jacques, “a new ‘culture war’ to pursue.” These stories generated a steady stream of angry, traffic-generating content and used TERF rhetoric as a way to cloak their conservatism in feminist-pandering language around “concern for women.” And framing transphobia as concern for women is a position that’s supported across the political spectrum; trans writers have even been asked by their editors not to speak out against other journalists’ transphobia.

By the time the GRA consultation opened in 2018—and accepted public submissions for several months—it felt like British media had accepted anti-trans sentiment as gospel. Organizations like Fair Play for Women and Woman’s Place UK organized campaigns to persuade the public to tell the government how trans inclusion was a threat to women. The Guardian published an editorial that argued trans people’s lived experiences and cis women’s concerns were both equally valid. It was swiftly disavowed by its American branch.

“Framing transphobia as concern for women is a position that’s supported across the political spectrum.”

Boris Johnson’s government was silent on GRA reforms until the summer of 2020, when leaks suggested that the government felt results were “skewed by an avalanche of responses generated by trans rights groups.” When the results were released in September, they showed that between 64 percent and 84 percent of respondents wanted to simplify and demedicalize the GRC process. About 20 percent of responses were associated with organizations like Fair Play for Women. The government announced they would make obtaining a Gender Registration Certificate cheaper and digitized—steps completely unrelated to the consultation—but not reform it, leaving the process the same as it’s been since its inception in 2004. (Scotland, which has its own trans health care system, ran a separate GRA consultation in 2020. Analysis is currently delayed due to COVID-19.)

In the end, despite widespread support for reforms, transphobia won out.

As transphobia continues to attract attention and shape policy, U.K. media continues to give trans issues outsized negative coverage. Even more, there are routinely new institutional attacks on trans rights—whether it’s the BBC banning some staff from publicly commenting on “the trans issue,” the trans man officially named as his child’s “mother” losing his court case to revise it, the Twitter troll cleared of wrongdoing for harassing a trans woman or the company that stopped filling hormone prescriptions.

Pearce says she’s even been used as a stand-in for trans views on topics she’s not actually engaged with. “Someone cited me in an article about toilets, and claimed I had said all kinds of things about gender-neutral toilets in my book Understanding Trans Health” that, she says, were not present in the book. “I went and got up the PDF version of my book and did a search on it, just to be sure I wasn’t making it up. There was not a single reference to the concept.”

It’s become harder just to exist as a trans person in such a hostile environment—both in the press and online—that’s trying to turn public opinion against trans people. “We have had to report people to the police for continued and insistent harassment on social media,” says Fox Fisher, speaking on behalf of themself and Owl.

To get through it all, trans people rely on their allies and on one another. Increasingly, trans people are taking matters into their own hands: Running mutual aid funds, dispensing health advice, looking after each other and fighting for a better world.

A 2019 charity livestream for Mermaids, for instance, raised more than USD$347,000 and featured celebrities including U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, activist Chelsea Manning, actress Mara Wilson and author Chuck Tingle. “What this [livestream] actually shows you is how people really think and feel,” Mermaids’ CEO Susie Green says. “Look at the allies and look at all these LGBT people saying ‘trans rights are human rights’ and ‘protect trans kids’… it was just like wall-to-wall love.”

For Pearce, the next steps aren’t about trying to fight TERFs, but rather focusing on making real-world change. “We are living in an age of grassroots trans activism, where really exciting and innovative things are happening,” she says. “If anything, it shows how far away that media coverage is from the reality of our lives.”

Correction: January 21, 2021 2:56 pmA previous version of this story incorrectly referred to the High Court of England and Wales as the U.K. High Court. The story has been amended.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra