An independent review into the Toronto Police Service’s (TPS) handling of missing person cases—including murders committed by serial killer Bruce McArthur—finds “serious systemic issues” in how investigations involving marginalized people are handled.

Titled Missing and Missed, the wide-ranging report released on Apr. 13 by the Independent Civilian Review into Missing Person Investigations contains 151 recommendations for how the TPS must reform to better serve LGBTQ2S+ and other marginalized communities.

“The recommendations explain how the Service must forge a very different relationship with the diverse communities it serves if it wishes to break down barriers to reporting and information-sharing, and it must understand and draw upon marginalized and vulnerable communities to advance the investigations into disappearances within them,” lead author Justice Gloria J. Epstein wrote in the report’s executive summary.

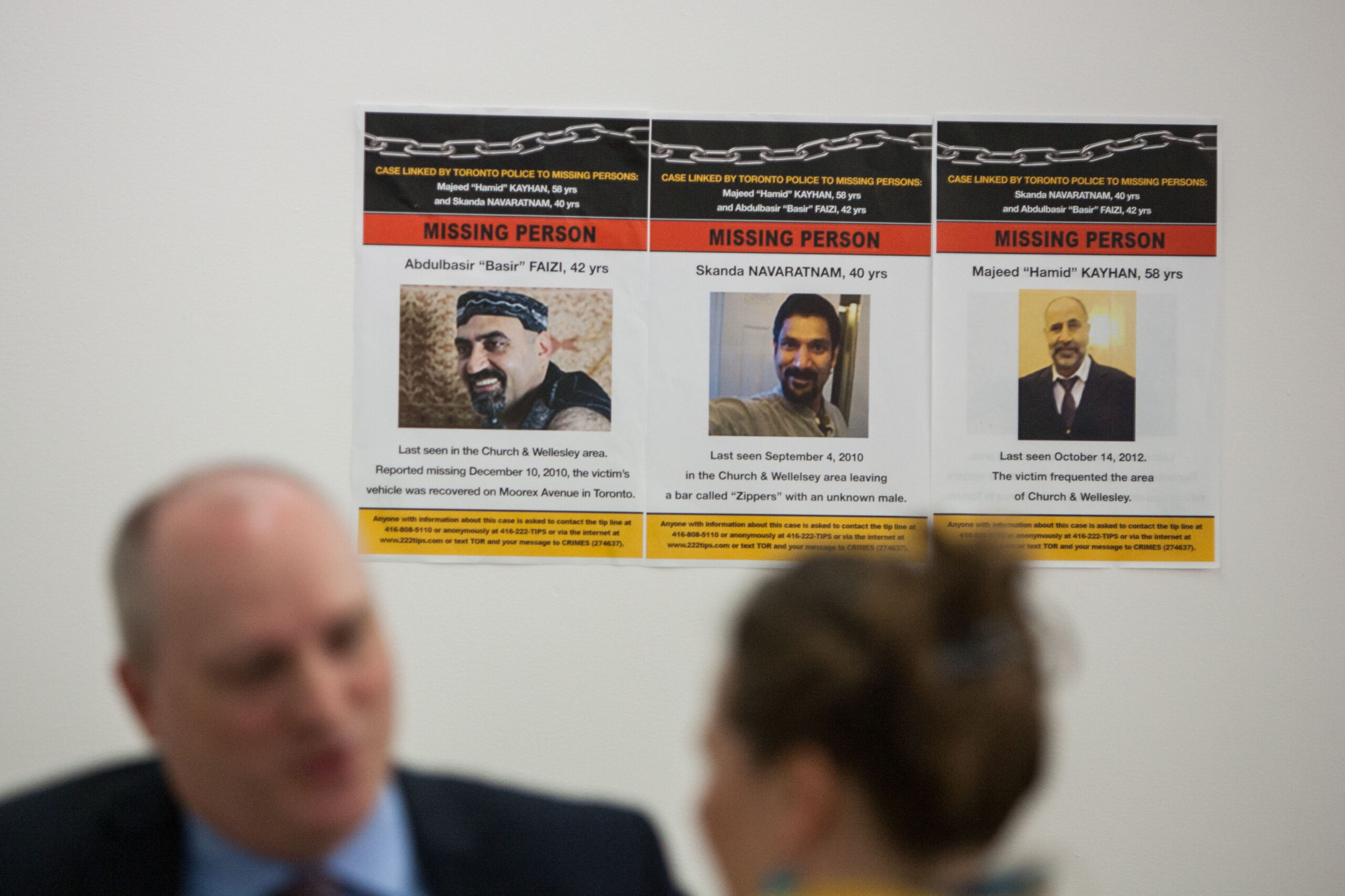

The report was commissioned in 2018 following the arrest of McArthur, who murdered eight men in Toronto’s Gay Village between 2010 and 2017. McArthur will serve eight concurrent life sentences in the deaths of Selim Esen, Andrew Kinsman, Majeed Kayhan, Dean Lisowick, Soroush Mahmudi, Skandaraj Navaratnam, Abdulbasir Faizi and Kirushna Kumar Kanagaratnam.

As details emerged regarding the murders, so too did questions about the TPS’s handling of the case—including a refusal to attribute mounting disappearances in the city’s Gay Village to a serial killer despite community outcry. Police did not arrest McArthur until 2018, despite conducting multiple interviews with him throughout the investigation and obtaining evidence linking him to the victims.

McArthur was only brought in after the disappearance of Andrew Kinsman, one of two white victims.

Credit: Nick Lachance/Xtra

Now, the independent review has determined that not only did the TPS display “profound systemic failure” in how it handled the disappearances of McArthur’s victims, but that failure continued in other missing persons investigations as well, particularly those involving LGBTQ2S+, Indigenous, racialized and other marginalized people. In the report, Epstein also looked into two other disappearances in the Gay Village during that time period—the cases of Tess Richey and Alloura Wells—and how police mishandled those investigations.

“Systems and practices that were in place discriminate against the LGBTQ2S+ community and marginalized and vulnerable communities generally,” Epstein said during a news conference Tuesday. “The report calls on the City of Toronto to partner with the [police] board, the service and the community to make Toronto a leader in how these cases are addressed.”

Epstein describes the recommendations as “broad-ranging and, if implemented, transformative.” The report calls on the TPS to develop a plan this summer for implementing all 151 recommendations for change and to release a detailed report by April 30, 2022 on how the service is implementing them.

Epstein says the 31 months spent compiling the report and interviewing stakeholders fundamentally changed how she views Toronto.

“It’s changed me. It has changed who I am, what I understand about people and I half-jokingly say that I almost wish I had done the review before my 25 years as a judge, because I think I would’ve been a better judge,” she said.

Here are five key recommendations from the report and what they mean. The full 1,109-page report is available to the public.

Bringing community supports into missing persons cases

Recommendation 36: The Toronto Police Services Board and the Toronto Police Service should work with the City of Toronto, provincial and federal governments, and social service, public health, and community agencies and not-for-profit organizations to build capacity for non-policing agencies and organizations to assume responsibilities consistent with the proposed mid-term and long-term models.

Both Epstein and the report’s lead counsel, Mark Sandler, say the biggest takeaway from the report is an urgency to revise how Toronto police handle missing persons cases in the short-, medium- and long-term. The report advocates for shifting certain cases away from police responsibility and toward community and civilian investigations.

“What we found is so many missing persons cases have so much more to do with social issues, so much more to do with prevention strategies […] and they’re not policing issues,” Sandler said. “The model contemplates triaging of missing persons cases so that the right people and the right agencies are doing the work associated with these cases.”

The report outlines a “groundbreaking” approach based on international examples, which involve triaging a missing person case to the appropriate agency—whether that’s a criminal investigation through police, or a more community-oriented investigation through social services.

“It shouldn’t be the loud voices that get different treatment,” Epstein said. “Everybody should get treated equally.”.

Re-evaluating public safety warnings

Recommendation 81: The Toronto Police Service should re-evaluate its existing decision-making processes for issuing public safety warnings. At a minimum, in relation to major case investigations, the major case manager should make the ultimate decision, in consultation with the Service’s Corporate Communications, as to whether a public safety warning is required. These types of decisions should be made, whenever possible, in partnership or in consultation with community leaders.

A key moment of the investigation into the McArthur murders came when police refused to acknowledge that the string of disappearances could be the work of a serial killer.

“To the detriment of the McArthur-related investigations, the Toronto police were very slow in identifying links among the missing person cases. There were lost opportunities to learn that a serial killer was on the loose, as many community members feared, and that McArthur was that killer,” Epstein writes.

Epstein calls the inability of the police to attribute the disappearances to a serial killer possibly the “most troubling systemic failure,” and argues lives would have been saved had the TPS issued a public safety warning sooner.

In mid-July 2017, a public warning in relation to gay men using social media was prepared for release but was vetoed by TPS management, who feared drawing connections between the victims’ use of social media and their deaths. As a result, no such warning was released until December 2017.

In the report, Epstein argues for greater consultation between the TPS and the community—in this case the LGBTQ2S+ community—to ensure these warnings are issued before it’s too late.

“If affected communities do not trust the police because they feel the police do not trust them, investigations will inevitably suffer, and public confidence and support for the police will be eroded. Indeed, that is precisely what has happened in Toronto, especially in traditionally marginalized and vulnerable communities,” Epstein writes. “My recommendations suggest a fundamental shift in how the police share information with communities.”

Re-establishing trust between police and marginalized communities

Recommendation 112: The Toronto Police Service should consider incorporating into its Missing Persons Procedure, a third-party or “distance” reporting system (where trusted community leaders, organizations, or agencies are designated to transmit, anonymously if necessary, missing person reports or information to the police).

A recurring theme throughout the report is distrust between marginalized communities and the TPS, the result of a legacy of criminalization. In the report, Epstein outlines interviews and consultations with community members that indicate a deep distrust of police, tracing back to incidents such as the 1981 Toronto bathhouse raids.

“A number of participants indicated that, if they were in danger, going to the police would be a ‘last option’ because of their fear of being arrested or being targeted themselves,” she writes. “Some communities have come to rely on themselves for safety because they do not feel protected or served by the police.”

She stressed that this distrust is not simply a legacy issue, but an ongoing and systemic rift between the police and LGBTQ2S+, Black and Indigenous community members. The report outlines the over-policing and under-servicing of these communities from the perspective of sex workers, LGBTQ2S+ and racialized community members and those with precarious immigration status.

And while Sandler acknowledges the scope of the report does not call for changes to criminal law such as decriminalizing drug possession, it does call on police to reform how they approach and prioritize cases involving marginalized communities.

“You have to have a strong relationship built on trust in order to work well with communities, not just in this area of investigation, but in all manner of investigations,” Epstein said. “Missing person investigations simply work better if there’s a trusting relationship so communication and information flows more freely.”

In the recommendations, Epstein calls on the police to establish safe and secure reporting methods as a way to ensure marginalized communities feel comfortable reporting missing persons to police without fear of personal repercussions. Epstein says the police must work to reestablish trust with these communities.

Acknowledging the failures of the Toronto police

Recommendation 113: The Toronto Police Service and the Toronto Police Services Board should consider whether they wish to acknowledge the deficiencies identified in this Report, together with the adverse impact they have had on those communities and individuals directly affected. Such an acknowledgement should be made only if heartfelt, if it is accompanied by a detailed action plan for change that is subject to independent monitoring, and if the content of the acknowledgement and the action plan is developed in partnership with communities.

This recommendation calls on police to acknowledge their failures and pledge reform moving forward. It also calls for apologies regarding public comments made during the McArthur investigation, like the denial that a serial killer was at work.

Sandler described the comments made by police to the media and the public as “deeply unfortunate.”

“It was unsupported by what existed at the time, and [the then-police chief] was simply incorrect,” Sandler said. “It was deeply unfortunate and deeply hurtful to the LGBTQ2S+ community, particularly when shortly thereafter, McArthur was arrested.”

Esptein acknowledged that the recommendations will not be implemented “overnight.”

“Make no mistake, if I think there has been a lull, if I think there has been an unexplained delay, I’m going to be making some calls,” she said. “It matters enough to me and to others that these recommendations will be implemented and […] I’m confident they will.”

Investing in better policing

Recommendation 10: The Toronto Police Services Board should be allocated sufficient funding to ensure it can perform its extensive governance and oversight responsibilities under the Police Services Act and the new Community Safety and Policing Act, 2019.

Finally and notably, the report advocates for increased funding to the police. During Tuesday’s news conference, Epstein acknowledged ongoing international conversations around police defunding and abolition, but argued that many of the changes outlined in her report require resources.

“Some of the recommendations […] do require significant investment,” Epstein said. “I am well aware that these recommendations come at a time when there are pressures on the city and the board to reduce the service’s budget. But the failure to act comes at a far more substantial cost, a cost to lives.”

Epstein stressed that the report also describes the need for a transparency process outlining how that funding would be used, and an accountability process to ensure police are using for reform.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra