David Gallant, a Brampton-based game developer. Credit: Xtra

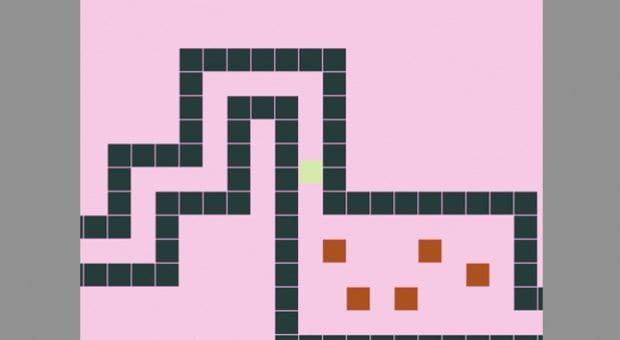

A graphic from Dys4ia, a game about hormone replacement therapy. Credit: Xtra

Merritt Kopas, a Toronto native who designed Lim. Credit: Xtra

Game critic Mattie Brice. Credit: Xtra

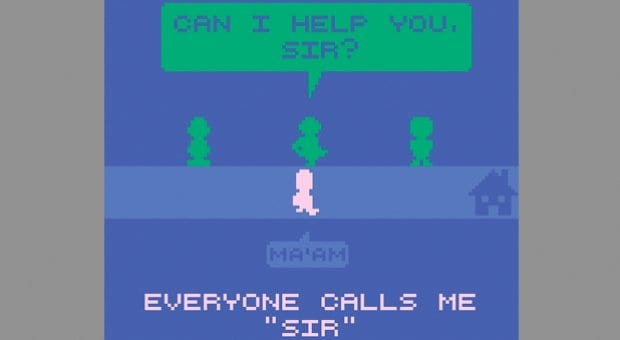

A screenshot from Mainichi, a game designed by Brice that simulates the everyday putdowns Brice faces as a trans woman of colour. Credit: Xtra

Lim is a deceptively simple game. I was confused when I first booted it up. Dull brownish squares make up the title in large capital letters — it all looked almost too minimalistic.

I pride myself on the number of games I’ve played over the years, so I was a bit abashed that I couldn’t immediately clue in to what to do. There are no points. No timer. There is no heterosexual, dark-haired white male protagonist in his 30s. In Lim, I controlled one of the squares, and the vague goal seemed to be to navigate through the winding pathway in which I was trapped.

But the task isn’t easy. Other coloured squares of either brown or blue would perceive me as the opposite colour — as the enemy — and before long they were attacking from all directions. The screen shook violently as each square slammed into me. I was weak and easily pushed around, unable to fight back.

I didn’t immediately see the option of pressing “Z to blend in” — perhaps I chose to ignore it. There is no timer, after all, and no “lives”; even if I was knocked around, my square was invincible.

Except I wasn’t.

It didn’t take long for the endless assaults to become grating. Not blending in became increasingly difficult until finally, progress became impossible. I betrayed my instincts and hit Z.

***

Few would guess just from playing Lim that key parts of the game draw on Merritt Kopas’s experiences of choosing a public bathroom early in her transition. Since she created the game in August last year, the Toronto native, currently based in Seattle, has come to be regarded as one of several key people pushing the boundaries of the types of experiences video games can deliver, and the types of voices they can represent.

Among them, some of the most visible — and vocal — are queer women like Kopas.

“I wanted to inspire that feeling of self-questioning and self-doubt in the player,” Kopas tells me over Skype, recalling her first summer moving through the world as a trans woman. At the time, she was doing graduate studies in sociology at the University of Washington.

She tries to convey the split-second, random and often unconscious decisions she has to make to try to maximize her safety in any given situation. She equates playing Lim to “walking into a space and having no idea how people are going to treat you.”

The same sense of dread returned when I played Mainichi, created by game critic and San Francisco State University student Mattie Brice. While Mainichi’s gameplay is different — it uses human sprites to simulate the everyday barrage of putdowns Brice faces as a trans woman of colour — it clearly explores similar themes. As with Lim, the message derived here was largely up to me.

The only title in the same vein to offer its audience an explanation is perhaps also the most well-known among flash-game enthusiasts and one of the genre’s earliest entries. Dys4ia, by American game designer and author Anna Anthropy, first appeared last year on Newgrounds, the do-it-yourself game community website. Shortly after, it was featured on the front page, and today the game has garnered nearly 450,000 views and 800 player reviews.

Anthropy’s disclaimer reads, “This is an autobiographical game about my experiences with hormone replacement therapy.”

***

It came as no surprise to the designers when the hyper-personal nature of their games and their unusual subject matter garnered attention.

Some notable reaction came from Samantha Allen and her students. The instructor and PhD student at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, decided to incorporate Lim, Mainichi and Dys4ia into her first-year gender-studies course.

When she speaks with me, she has just returned from a trip to Vancouver, where she presented at the second annual Feminists in Games workshop.

“Traditionally, the format of the classroom is that I’m up there lecturing,” Allen says. “I’m responsible for guiding [students] through it and offering them possible interpretations of the material.”

During the past term, she had expressed concerns that her classroom presentations would be reduced to “a display, a spectacle that my students could observe but not one that would require their active engagement.”

Teaching with video games gave them a tool to learn and explore for themselves rather than being lectured to, she says.

Allen describes one particularly touching moment when a girl playing Mainichi encountered in-game street harassment. “It looked like she was about to cry,” she says. “For me, this was such a powerful moment of empathy, where playing this game had really allowed the student to identify with the character. As a transgender woman myself, it was encouraging to see her for a few moments really understanding what my day is like.”

For Ivan Metzger, who was also in Allen’s class, these games bridge cultural gaps that “interfere with people’s abilities to relate and empathize.” He says Dys4ia, in particular, opened his eyes.

As tempting as it would be to slap a “queer” label on these short interactive experiences, doing so would not do them justice, Kopas says.

The label would also pose a barrier to those interested in trying their hand, Brice says. “People have started to think because they aren’t queer, they can’t make these games,” she writes in an email. “Nothing’s further from the truth!”

***

Few have been more instrumental in pushing for diversity in video games than Anthropy.

In her book Rise of the Videogame Zinesters: How Freaks, Normals, Amateurs, Artists, Dreamers, Drop-outs, Queers, Housewives, and People Like You Are Taking Back an Art Form, she argues that it is people in marginalized groups who must help the medium mature.

“If video games are compared unfavourably to other art forms such as novels and songs and films … it is likely a result of how limited a perspective [they] have offered up to this point,” Anthropy writes. “If a form has attracted so many authors, so many voices, that several of them come from experiences outside the social norm … can’t that form be said to have reached cultural maturity?”

Anthropy, Kopas, Brice and Allen are only a few of a growing choir of voices calling for greater diversity in video games. Yet to the industry, they are decidedly outsiders.

This fight is also taking place in the world of mainstream gaming, but rebels like David Gallant are few and far between.

The day I meet Gallant in Toronto, he has an air of defeat about him. The Brampton-based game developer is known in some circles as the creator of I Get This Call Every Day, a satirical game about working at a customer service call centre — a game that got him fired from the Canada Revenue Agency. A bearded man in his early 30s, Gallant looks the part of someone you’d imagine to be very active in Toronto’s indie game sphere.

And he was until this past May, when he took to the gaming website Gamasutra to denounce the community for what he described as “exclusionary behaviour.”

“The more I have reached out into the community, the more I have come up against people who are in less privileged positions than myself,” Gallant says.

He says he began to notice prejudice from friends and colleagues, some he had long admired. He cited one example in which a friend from the local indie scene harassed and eventually drove a female colleague out of town while the community stood by.

For the first time, Gallant says, “it shook my faith.”

This culture is all too familiar to Anthropy, who says she, on the other hand, has no misgivings about influencing mainstream gaming. Instead, she focuses her efforts entirely on getting newly available game-making tools into the hands of marginalized people. “Our discussions of politics seem to always be focused on … images of marginalized people, rather than on the people themselves and on helping them gain power,” she says. “Building a culture where anyone can make a game and not be silenced … that’s a change that will transform our culture.”

Within the last few years, a number of alternative game conferences and workshops have sprung up, including the Queerness and Games, Different Games and Feminists in Games conferences, all of which offer views on new directions in which the medium can head.

Similarly, Toronto’s Dames Making Games organization, of which Gallant is now a member, provides programming workshops to minorities, including members of the queer community.

As recently as March, the Tropes vs Women in Video Games web series launched, having raised 26 times its initial fundraising goal. As of writing, it has already produced several videos analyzing sexism in games.

Even if judging solely based on the number of people doing work similar to Kopas, Brice and Anthropy, change is coming.

“I’m heartened,” Kopas says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra