Vancouver lawyer Rob Hughes represented newcomer Sombede Korak. Credit: Paula Stromberg

Kumasi has one of the largest markets in West Africa. Credit: Paula Stromberg

Exterior famous Ashanti shrine outside Kumasi- Unesco site. Credit: Paula Stromberg

Vertebrae amulets, fetishes in Ashanti shrine outside Kumasi. Credit: Paula Stromberg

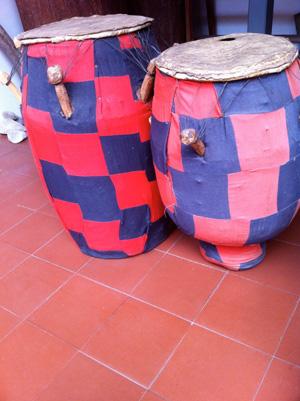

Funerary drums, Ashanti region. Credit: Paula Stromberg

Famous Ashanti shrine outside Kumasi. Credit: Paula Stromberg

Rainbow Refugee Committee marches in the 2011 Vancouver Pride parade. Credit: Paula Stromberg

Imagine if your family published a newspaper story saying you were evil and that the story made some neighbours feel obligated to smash your skull with rocks. There are thousands of stories like this in Africa. This one is horrific but has a happy ending.

We know there’s a crisis facing lesbian, gay and transgender people around the globe.

Homosexuality is criminal in about 77 countries, including five with the death penalty, and numbers are growing. Particularly in Africa, queer people are being terrorized into the closet, prison cells or the club-wielding hands of lynch mobs. Many religious groups exacerbate this terror to mobilize against wicked Western morals and the “previously unknown” foreign import – homosexuality.

Laws against homosexuality did not exist in Africa until the late 19th century under British colonization. Nowadays, African leaders who promote gay hatred maintain the colonialist mentality. Governments crack down on homosexuals as a way to unite Christians and Muslims in Africa.

This could seem comical, except that modern queer Africans are fleeing homelands where they’ve been imprisoned, blackmailed or tortured because of their sexuality or gender identity. Many are physically or sexually assaulted by police or religious officials.

In 2011, the Canadian government amended the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act and other legislation claimed to improve Canada’s asylum system for refugees.

Vancouver lawyer Rob Hughes, well known for representing gay and lesbian refugees over the past 20 years, says Canadian law allows refugee protection for those who can demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution. They must also prove that they cannot be safe in another part of their country and that their own state government is unable or unwilling to protect them.

In Vancouver, Hughes represented newcomer Sombede Korak at a refugee hearing in 2011. Korak is a gay man who recently fled West Africa. He’s from Ghana’s second largest city, Kumasi, in the centre of the country’s Ashanti region.

Although Korak is now safely in Canada, he prefers to remain anonymous, and his name here is a psudonym. This is his story.

Kumasi is the capital of Ghana’s kente cloth and gold-producing Ashanti region. Much of Ghana’s wealth and many of its leaders come from this area. The Ashanti ethnic group is estimated to comprise 19 percent of the population, making it the largest cultural group in Ghana.

As a young Ashanti boy, Korak knew he was different. One day, after he wore his sister’s clothes on the street, his father beat him so severely it took several weeks to recover.

His adolescence was difficult, but at age 20, he met his first boyfriend. “We stole time together,” says Korak in an interview in Vancouver.

“That same year, 2001, a male relative demanded that I date a woman and have sex to prove I was a man, not a homosexual. My family forced me into a heterosexual relationship.”

Because his 18-year-old girlfriend insisted they live together after she had twins, Korak rented two rooms. He attended the Catholic Church, hoping a Christian god might trump African traditions. “Secretly I kept seeing my boyfriend,” Korak says. His traditionalist family was happy that he sired children, but after a couple of years, one of the twins died.

“Twins are a good omen, so according to Ashanti tradition, I had to perform a ceremony to make the dead child’s spirit return in the next baby. Our Ashanti religion, a mix of spiritual and supernatural powers, includes ancestor worship. Shaming the ancestors is an unforgivable sin,” he explains.

By 2008, he and his girlfriend had produced another child. “Everyone agreed the baby had the same face and spirit as the one that died,” he says. “Spiritual beliefs, customary practices and fetish rituals are part of everyday life in Ghana.”

Korak was rarely home with the babies and their mother. He had a successful business and claimed his trading operation kept him absent, but all along, between 2000 and 2009, he and his boyfriend continued their relationship.

“One afternoon, my boyfriend and I were at a hotel that rented rooms by the hour. Suddenly, my boyfriend’s family broke the door and barged into the room, catching us in bed. The mother and sisters screamed and made a loud scene. There was lots of shouting.

“I ran away. Later, I tried to call my boyfriend several times, but his mobile phone was dead. That was the last time we saw each other. We’d been together nine years.” Of course, the boyfriend’s family made sure Korak’s relatives found out he’d been caught red-handed as a homosexual.

“Oh, it was bad. In reaction, my family ordered I go to an Ashanti bush shrine to be cleansed of evil spirits. I tried to remind them I was Roman Catholic, but it did not help. They insisted I go for the shrine ritual.”

It is important to note these cleansing rituals are not confined just to African traditionalist religions. For the past several years in Ghana, the fastest-growing evangelical and other Christian churches embrace the notion of the Devil, spirit possession and witch demonology. African leaders know that a church without exorcism or so-called deliverance sessions means empty pews.

“A different religion like being Roman Catholic made no difference,” he says. “My family insisted I be cleansed. The shrine priest would perform painful rituals to drive out the Devil and make me straight.”

When I show Korak my photos of an Ashanti shrine 20 kilometres outside Kumasi, he shakes his head, saying that a painted shrine, a town shrine, does not hold the horror of a bush shrine.

“You have to pay money to be beaten. The priest takes you far into the bush, chains you to a large rock at the shrine, throws stones and clubs you. They would shave my head and poison me – or likely kill me in the bush shrine. Acid could be forced down my throat as part of cleansing the evil, being homosexual. Because I broke a serious taboo, they could treat me the same as a witch.

“When people die in a bush shrine there is rarely a police investigation or autopsy,” he says.

Rather than undergo a cleansing ritual that was likely to kill him, Korak ran away. His family searched for him. Relatives gave a story to Ghana’s National Democrat newspaper, announcing they were hunting him for a cleansing ceremony.

The article was as good as signing a death warrant. Ashanti beliefs – that being a homosexual shames the ancestors – meant anyone could beat him to death on sight. He was known to have an evil spirit. Some religions teach that killing a homosexual is like beating the Devil.

Realizing he could not stay hidden in Ghana, Korak applied for a visa and came to Canada as a tourist. In Vancouver, the Rainbow Refugee Committee helped him make an application to be accepted in Canada.

Korak must keep details of his Canadian refugee claim private for his own safety and to protect those Ghanians who helped him, but he does reveal that after he’d arrived in Canada, a Kumasi friend mailed him a copy of the newspaper story about his family’s hunt. In a strange twist, the news story’s open invitation to violently cleanse the Devil saved his life.

Rob Hughes explains: “The Canadian Immigration and Refugee Board member who heard the case said she ruled in favour because of the proven death threat [Korak] faced at home. The newspaper clipping corroborated details given earlier in the refugee application about the danger he faced.”

Despite being safely in Vancouver, Korak is still in the closet. Old beliefs die hard. He is afraid of being discovered as a homosexual by fellow Ghanians at his Vancouver church. In a strange new land, he needs continued contact with his own culture. However, many newcomers are still socially conservative. Many still hate gays as a God-given right. He does not feel safe.

Perhaps this can be a reminder for us. Hatred and exorcisms are not confined to African traditional religions. With rapid growth of Pentecostal, charismatic and evangelical churches on that continent, they are harnessing Africans’ fear of witchcraft and supernatural powers. Both religions and governments gain power by demonizing gays and lesbians, denouncing low Western morals. It is cheaper for African governments to look engaged by passing anti-gay laws than to deliver clean water, sewage systems or education.

Media reports such as The Rachel Maddow Show document US fundamentalist churches that finance African pastors who preach against gay rights and women’s rights. African congregations see their hate-speaking pastors quoted internationally by conservative media outlets, getting publicity for outlandish pronouncements that North American pastors would be laughed at or arrested for here – and thus attracting US dollars. African pastors who say the right thing become rich and famous with American Christian help.

American money shaping African morals and African souls – another colonization of the spirit.

Meanwhile, rising immigration from conservative nations into Canada and all of North America and Europe is creating new pressures. Local fundamentalists promote homosexual hatred with evangelical fervor. For Canadian queer people, protecting the right to live safely, be treated with dignity, overcome internalized homophobia, come out and fight back against hate-mongering religious messages must remain a never-ending process.

Human rights workers and queer activists need our continued support both in Canada and around the world.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra