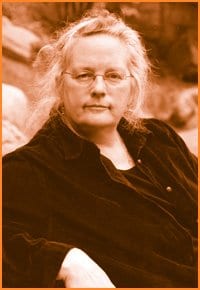

“I certainly wasn’t going to be marrying anybody again. In 1975 I left my second husband and I said, then and many times thereafter, I will not get married again-not even for the revolution, I said.” Frances Wasserlein shakes her head.

Now that the revolution is upon us, the executive producer of the Vancouver Music Festival concedes that she did, in fact, get married last summer in the park by a United Church minister, “Thirty minutes before the gates opened at last year’s festival.” After the ceremony, “I put my radio back on and we opened the gates.” She grins.

Her partner, Marguerite chimes in, “You’ve got to think about this seriously because we’re the generation of people who did this-who made it possible for this to happen, and besides, we need to do it so that we’re standing in the door so they can’t close it.”

Wasserlein says “it’s really important for the love that dare not speak its name to go around shouting-which is why we got married.”

She grins again, “It’s just kind of cool to say to people, ‘Hi, how are you? And this is my wife, Marguerite.’ I am right on the front edge of the baby boom, the 57-year-old points out. Who knew that this would happen?”

Wasserlein taught history and women’s studies and lesbian studies at SFU and Langara College. In her younger days she worked as a bookkeeper, a clerical worker, and was a vigilant officer in her union. She is a founding mother of Women Against Violence Against Women (WAVAW) and ran three consecutive elections for city council, twice with COPE in 1993 and ’96, and as an independent in 1999.

In 1978 with The Coalition Against Discrimination, Wasserlein used phone trees to organize demonstrations. Today she uses the Internet. “Every once in a while I think about that when I go bink!” She hits an invisible keyboard on the table with her finger. “At work I send out 4000 e-mails in a second. I think it has had a really big effect on the capacity of one or two people to do enormous organizing tasks-which is not to say that enormous organizing tasks weren’t done by one or two people in the ’60s and ’70s, because I think they were. The kind of contact that it’s possible to have across the globe is so remarkable.”

Today her inspiration comes from a different place than it did when she became an activist. “I feed a huge sense of responsibility for trying to do what needs to be done to ensure that little Michael, my very dear friend’s daughter who turned six on Sunday, can grow up to be a woman like me, in her late 50s, sitting looking over her life and looking to the future to make sure all the little girls and boys that she knows are going to have a good life. That’s, I think, the responsibility.

“I’m not quite sure when I realized that it wasn’t anymore about me-that it was really about making sure there’s a world in the literal sense. That passion is a different kind. It’s kind of quieter and it’s not fuelled by anger. It’s actually fuelled by hope. That’s the biggest difference for me between now and then. I’m calmer. I know what I’m doing. I don’t have to shake my fist at people and I’m not scared of anybody-so it’s all easier now.

“I didn’t really even know I’d stopped being angry,” she muses. “I’m not sure when that stopped. I think anger is important and anger in a just cause is critical-but I think that perhaps the luxury of old age is hope. And I still have some-I have lots-and I want to make sure that everybody else gets to live long enough to know the difference.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra