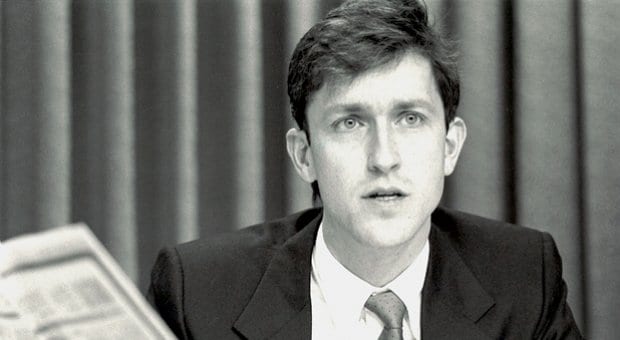

Svend Robinson in 1988, the year he paved the way as the first MP to come out in Canada. Credit: Phillip Hannan

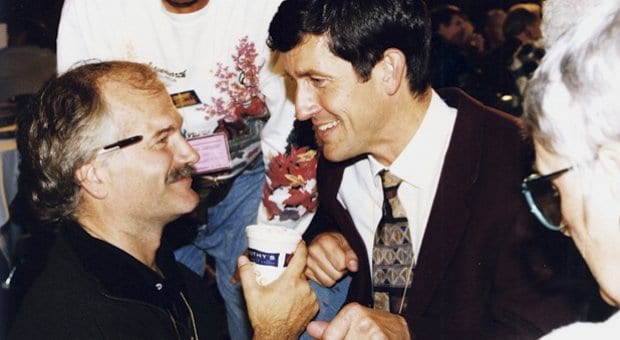

Svend Robinson and Jack Layton during the 1995 NDP leadership race. Layton was a member of Robinson’s campaign team. Credit: Courtesy of Graeme Truelove

As author Graeme Truelove recounts, Svend Robinson’s solidarity mission to Israel and Palestine in 2002 provoked a hostile reaction, both at the Israeli military checkpoint and in caucus back home. Credit: Courtesy of Graeme Truelove

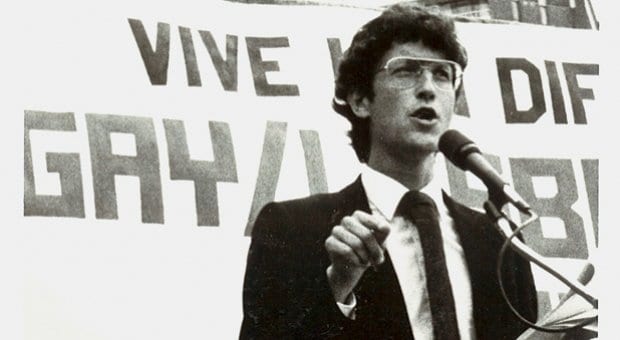

Svend Robinson, as MP of Burnaby in 1985, warns BC Premier Bill Bennett that gays and other minorities will not give up the battle for human rights, in spite of Bennett’s dismissal of the BC Human Rights Commission. Credit: David Myers

The jacket cover of Graeme Truelove's authorized biography of Svend Robinson. Credit: Courtesy of Graeme Truelove

Not long after Svend Robinson turned himself in to police for uncharacteristically pocketing a ring at a 2004 auction, Little Sister’s bookstore hung a powerful painting of a raven with a gleaming ring in its beak.

“Gay men are attracted to shiny objects,” co-owner Jim Deva told me at the time, by way of explaining not only Noel Silver’s work that so lovingly mocked Robinson, but also Svend’s jaw-dropping political suicide. “We’re the ravens of the human world.”

Gays correctly love to poke at those among us who rise high, keeping egos checked and irony front and centre. Still, it’s important to note that the raven painting replaced another Silver canvas that celebrated some of the activists and personalities of Vancouver’s lesbian and gay community. Standing tall among them in the original painting, himself the naked and shiny main object of attraction, was Saint Svend.

It’s even more important to note that the raven painting came down soon enough, with Saint Svend restored to his rightful place on the wall.

Now, nearly a decade later, Robinson’s first authorized biography — Svend Robinson: A Life in Politics, published in October by New Star Books — reveals previously unpublished personal tales and spotlights the constant creativity he brought to the too-often boring Canadian political stage.

Robinson was our political drama queen, staging dramatic events to bring attention to issues that were just becoming ripe enough for public consumption.

Author Graeme Truelove captures Robinson’s talent for rounding up both activists and average people with emotional personal stories to convince members of parliamentary committees to go further than they ever intended to go — with recommendations for gay rights, for example, in the 1985 report from the subcommittee on human rights.

As Truelove points out, Robinson often forged critical links between activists and the nation’s political establishment.

The author grew up in BC, now lives in Ottawa, and has not previously published a book. But Robinson gave Truelove access to his life, his clippings and his friends for the project.

Truelove was an intern in Robinson’s parliamentary office from 2002 to 2004, while studying political science at University of Ottawa, then followed in Robinson’s footsteps as a labourer-teacher for the respected Frontier College literacy organization. Still, Robinson was initially reluctant to agree to cooperate with a biographer, Truelove recalls, adding that he thinks he eventually got access by building trust.

“It’s such an intrusive process, digging into things from decades ago and sometimes passing judgment.”

Though Robinson skillfully brought public focus to his causes du jour as a politician, he usually tried to keep the focus off his personal life. But Truelove manages to pump a measure of blood into the political skeleton that most of us, previously, had been limited to seeing. We learn how Robinson’s mother far too literally sacrificed herself to an alcoholic husband who clearly never understood her graces and gifts. And we can almost feel young Svend’s pain at the verbal and physical assaults he took from the man who repeatedly uprooted his family, consigning the kids to struggle in a series of new schools.

Robinson could have turned out a mess and, in fact, became an alcoholic while studying at UBC, married to a woman yet feeling attracted to men. But he got off the bottle, honourably left the marriage, and seemed to have successfully channelled his demons until the ring incident.

To Truelove, Robinson’s mastery of house procedures, his strategic cunning and his capacity for absorbing detailed information allowed him to achieve far more in his 25 years in Parliament than probably any opposition MP in Canadian history.

Truelove details how Robinson organized and manipulated his way to a series of changes and additions to the proposed Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the early 1980s; if he’d won everything he wanted, this would arguably be a more fair and just nation.

Robinson also managed to focus public and political attention on a series of issues in which he has on the whole already been vindicated by history: abortion, prostitution, police harassment of gays, First Nations inequality and the right to die.

Of course, many people remember him best for his powerful coming-out speech in 1988, which encouraged a generation of closeted youth and adults, including his famous former lover, Senator Laurier LaPierre, to step more fully into their own lives.

Truelove also documents some of Robinson’s causes of particular interest to the gay and lesbian communities through the years, including passage of his own hate-propaganda bill; his support for marriage equality; his opposition to police harassment of gay bathhouses; his push for sex-trade laws; and his facilitation of presentations by gay activists and sex workers to parliamentary committee meetings.

But Truelove largely misses Robinson’s other work for gays and lesbians and others fighting to make their own decisions about what to read and how to use their bodies. Robinson publicly supported Little Sister’s in its fight against Canada Customs’ book seizures and for years worked unsuccessfully to strip Customs of the power to judge what art, literature and erotica should be allowed into Canada.

He also notably opposed — and organized opposition to — the Mulroney government’s proposed child-pornography bill that went overboard to target art and other erotica; the bill was pulled.

Even after he retired, Robinson spoke out (and lobbied his former colleagues) to kill bills passed by prime ministers Stephen Harper and Paul Martin that raised the age of sexual consent and stepped up policing of sexuality far beyond the child porn they ostensibly targeted.

It’s not well known how often Robinson was alone or nearly alone in caucus when standing up for sex issues, particularly prostitution and the age of consent. Vancouver East MP Libby Davies was often the only MP to support him on these issues, and later Bill Siksay, who replaced him in Burnaby, carried the torch.

These issues, and other causes, upset some caucus members and even resulted in provincial party leaders trying to intervene. “It got pretty ugly at times,” Robinson tells Xtra but refuses to go into detail.

On most gay issues and his own sexual orientation, though, Robinson says he received “solid and consistent support” from the moment he stepped into caucus, including from leader Ed Broadbent.

But when, early in his career in 1982, he told the audience of BC radio journalist Jack Webster that prostitution should be decriminalized and the bawdyhouse laws used against prostitutes and gay bathhouses repealed — the official position of the federal NDP — Robinson was publicly denounced by one caucus member and demoted from justice critic by Broadbent. “That was a painful experience,” he remembers.

Robinson remained consistently unrepentant, insisting that government be prevented from intruding into people’s sexual expression. Privacy rights go beyond the bedrooms of the nation that Pierre Trudeau wanted to protect from state policing, he says.

“People have a right to be fundamentally free to be who you want and to celebrate your sexuality. That’s a very precious freedom, and we have to continually fight for this.”

That openness makes him unlike most lesbian and gay politicians, who tend to steer clear of issues of sexual expression and censorship. “I found out gay politicians quite often will be lovey-dovey and say we’re like everyone else,” Robinson says. “But we aren’t like everyone else. I think we need to speak out and celebrate who we are.”

To Robinson, sexual expression and exploration is core to what it is to be gay. ”It’s very important that we remember that and celebrate that,” he says. And same-sex marriage “is not the be-all and end-all of who we are.”

Though media reports often framed him as a poor team player, Robinson takes the emphasis off caucus relations, when questioned. “I was a consummate team player. The teams I played with principally were the party and the constituency I represented for 25 years, and also the caucus. With all three teams I played fairly and honourably.”

In fact, Robinson’s eagerness to prove himself a team player led to perhaps his biggest political mistake — his surprise concession at the federal leadership race in 1995. He caved after the first ballot, thus making Alexa McDonough the early winner. That should have won him huge kudos as a team player from the new leader and caucus, but, as Truelove documents, it didn’t work out that way.

The youthful “rainbow coalition” that Robinson’s leadership run attracted to the party (“Sven-DP” was their favourite convention chant) felt betrayed by his early exit from the fight — they wanted their guy to go all the way, even to defeat. Some booed him, some walked out of the arena, and many left to join the Green Party or left electoral politics in disgust.

Whether he was the best team player or not, Robinson was clearly on the right side of history on most things — sometimes well ahead of his time. That’s good activism, if divisive party politics.

After the ring incident, Robinson was diagnosed as mentally ill and got help. His move to a town outside Geneva, Switzerland, at first glance seems a form of self-exile. But Truelove puts it in context: Robinson now puts his considerable political skills and parliamentary knowledge to work for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. And, like a good movie finale, he got the man — charming, smart and politically centrist Max Riveron — and two fluffy white Havanese dogs.

His enduring legacy far outshines a single moment with a gaudy piece of jewellery.

“For thousands of Canadians who struggled for representation in mainstream politics, Robinson articulated their vision of Canada with an unflinching precision unmatched by any other political figure,” Truelove writes. “For others he provoked a visceral loathing, not just because of the positions he took, but also because of the audacious manner in which he sometimes presented his point of view.”

In any case, he was, perhaps, the longest-lasting meteor to light up the normally dreary skies of Canadian politics, and the NDP in particular. He can take a deep bow. So can Truelove for capturing the spirit, as well as the resumé, of the man.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra