The fight for pensions for widowed gay and lesbian partners took its final step on May 16, when the Supreme Court Of Canada heard arguments in the case.

The court is expected to rule on the case later this year.

The plaintiffs — the same-sex widows — argued that the federal government is discriminating by refusing to pay Canada Pension Plan (CPP) survivor benefits to those whose partners died before Jan 1, 1998. They contend that benefits should be paid to all survivors whose partners died since 1985, when the Charter Of Rights And Freedoms came into effect.

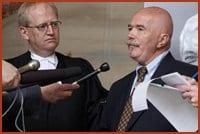

“Gays and lesbians are human beings entitled to equality,” Douglas Elliott, the plaintiffs’ lead lawyer, told the court. “It is a matter of right.”

The lawsuit was launched in 2001 by the late Toronto gay activist George Hislop, shortly after the federal government extended CPP survivors’ pension benefits to same-sex common-law couples. But the government decided arbitrarily that any deaths before Jan 1, 1998 would disqualify the survivor from pension benefits. The Ontario Court Of Appeal agreed in 2004 that the cut-off date violated the Charter.

Lawyers for the federal justice department told the court on May 16 that the government was following precedent in setting a cut-off date, and said the case could set a costly example in other cases.

“Parliament did exactly what this court has done in almost every Charter case,” said Roslyn Levine. “It applied the new law without retroactive effect.”

The government began making interim payments to widows in 2005, although the government has said it will claw back that money if the Supreme Court rules in their favour. If the plaintiffs are successful, the cost to the pension plan is expected to be about $80-million. Although the plaintiffs argued that that cost will be minimal, some justices seemed concerned.

Marshall Rothstein, recently appointed the newest Supreme, said the cost could not be ignored.

“The $80-million has to come from somewhere,” he said.

But other justices noted that the survivors and their late partners had all paid into the pension plan.

“They purchased rights under the Canada Pension Plan by contributing to it,” said Justice Ian Binnie. “Why should they suffer an unequal benefit?”

The court also heard arguments about two other issues where the Ontario Court Of Appeal ruled against the plaintiffs in 2004.

The Ontario court ruled that those applying for pensions were eligible for only one year of pension arrears from the time they filed a claim. The court also ruled that the dead were not allowed to bring suits, a ruling that would exclude the hundreds of survivors who have died since the lawsuit was filed.

In an interview several days before the hearing, Elliott said that the ruling on arrears failed to take into account the fact that before 2001, queers could not claim survivor benefits.

“It was pointless for gay people to file claim in those days. This administrative time limit should not stand in the way of securing a full pension. For a lot of these guys, their arrears are more valuable than their future pensions because they’re getting up there.

Elliott also said in that interview that ruling out the dead meant rewarding the discrimination they had faced.

“It’s a revolting proposition that people who were discriminated against could now lose and their estates have their pensions revoked.”

Elliott also expressed regret in the interview that Hislop, who died in October, 2005, would not be able to see the suit he had launched and fought so hard for reach the final stage.

“It’s obviously sad and poignant that he won’t be there,” he said. “We certainly are going to be inspired by his feisty example. He would certainly want to fight to the bitter end.”

Hislop’s partner of 28 years, Ronnie Shearer, died in April, 1986, after the Charter was passed. After the government began including same-sex survivors in 2000, Hislop applied twice for CPP benefits, but was turned down. That’s when he filed the lawsuit, which was eventually joined by about 1,500 other survivors.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra