This year marks the 50th anniversary of Xtra’s publisher, Pink Triangle Press, which was established in 1971 in Toronto, Canada. The aim of the press’ founding collective was to give a voice to the political and social concerns of gay men and lesbians and to advance the cause of sexual liberation. In November 1971, they launched the influential (and occasionally infamous) gay liberation newspaper, The Body Politic. Fifty years later, Xtra is exploring what sexual liberation means in the 21st century through the six-part series Protest and Pleasure by activist and writer Chanelle Gallant.

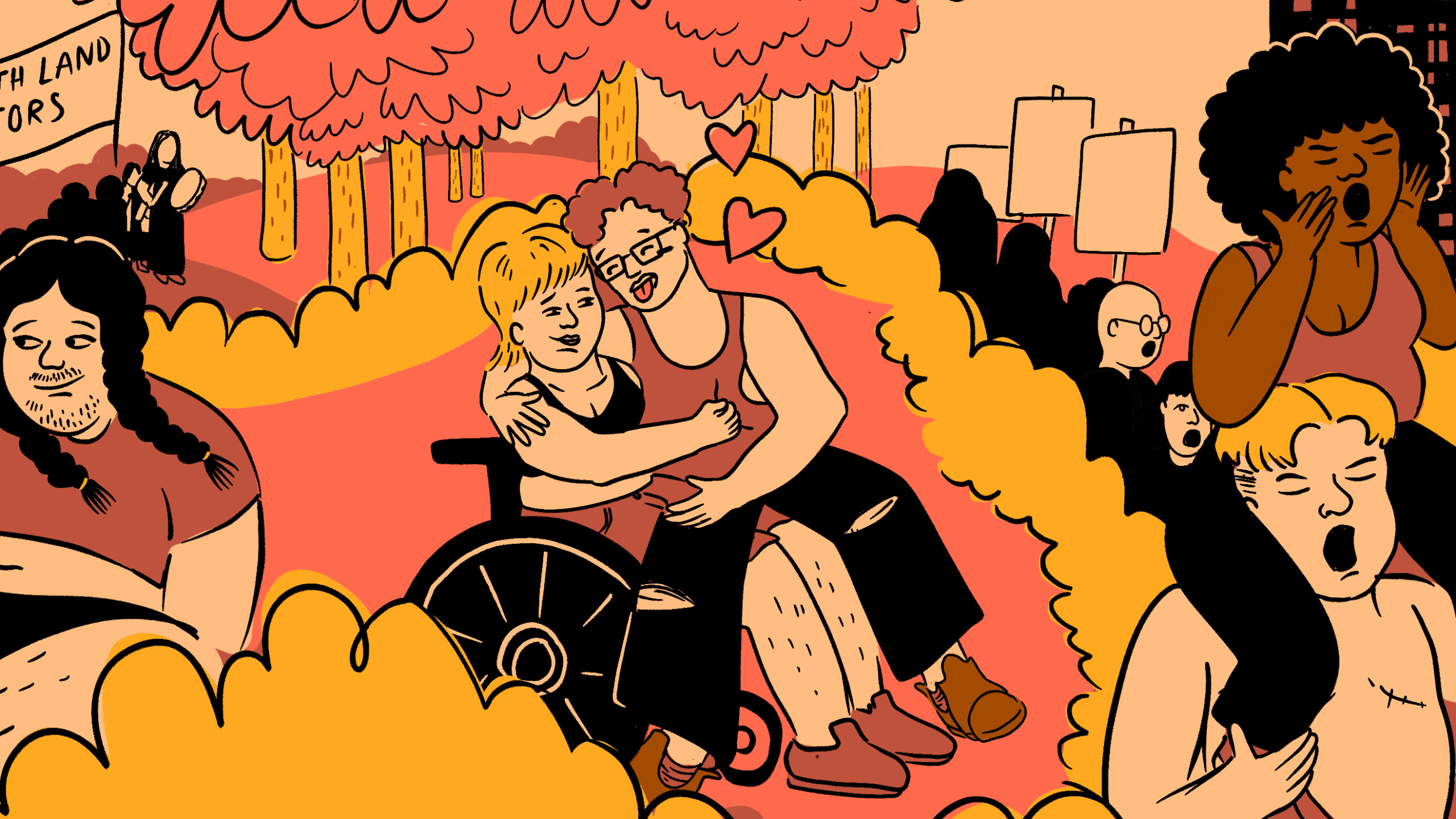

“There are endless possibilities of what sex can be and what pleasure can be, both orgasmic and non-orgasmic: Intimacy through vulnerability, building trust that makes sex hotter and sweeter. I’ve had great, great, great, great sex… and we never even left our chairs.” That’s Patty Berne, talking to me earlier this year about some of the hottest sex she’s ever had. Berne is the founder of Sins Invalid, a crew of queer, trans and BIPOC artists based in the San Francisco Bay Area, who make art and theory about disability and sex. In the 1990s, when Xtra’s publisher Pink Triangle Press proclaimed their mission as “daring to set love free,” it might not have been imagining a queer disabled woman of colour fucking her lover while both in their wheelchairs—but why not set love free for all bodies and minds?

Welcome to the first installment of Protest and Pleasure, a six-part series marking five decades since the founding of Pink Triangle Press, as well as the Stonewall Uprising in 1969 and the beginnings of the (incomplete) decriminalization of homosexuality across the U.S. and Canada.

Fifty years on, it’s worth considering how this movement succeeded and where it failed. Where is “sexual liberation” today?

On the one hand, we’ve seen tremendous advances in LGBTQ2S+ rights, such as anti-discrimination legislation and marriage equality, increased visibility and activism arising from the AIDS crisis, as well as a revolution in how LGBTQ2S+ people are seen and see themselves in media and in culture. Many of us can now live with our partners and care for them in sickness; we can be out at our jobs and watch a queer film with characters who don’t all die at the end. Hooray, thank god, three cheers for that. But for some, things didn’t get all that much better. Trans communities are under increasing attack through discriminatory legislation, Black trans women still get murdered or go to jail when they defend themselves (last year in the U.S., at least 44 trans or gender non-conforming people were killed, the majority of them Black or Latinx) and homeless youth are still disproportionately LGBTQ2S+.

But at least we can now have the sex we want, right? Kind of. For the most part, queer sex isn’t considered a crime or an illness in Canada and the U.S. But sexual and intimate violence are rampant, everyone is taught to think they’re doing sex wrong, young people learn nothing (or all the wrong things) about sexual consent and sex panics (about who can use which bathrooms and play on which sports team) remain a potent weapon for right-wing politicians. It would be hard to describe this as liberation.

I’ve spent most of my adult life fighting for sexual liberation. I’m embarrassed to use such a corny, old fashioned term, but it’s true. I’ve worked hard to free sexuality, for myself and for others, because I believe in sex as a wild, vexing and precious part of our humanity. I’ve seen how sex can be an electrifying pathway to our true selves; how it can heal and soothe; how it can be ordinary, sweet and awkward; how it can pay the bills or break up a marriage. And how it can—if that’s your thing—produce a baby. Astonishing, really. Like the song says, anything you want done, baby, sex can do it, naturally.

But maybe my favourite thing about sex is how it expresses the human struggle to be free in its most intimate form. I want that for all of us: The freedom to be honest about our body’s truths and desires. Two decades ago, that meant I was fighting the homophobic police raid on the women’s bathhouse in Toronto. For the last 17 years I’ve been fighting for the rights of sex workers. In between, I managed a feminist sex store, started the Feminist Porn Awards, wrote a national sex column, hosted a radio show on sexual politics and, of course, had a whole lot of sex.

Today my “sexual liberation work” includes fighting for migrant and racial justice and against criminalization, prisons and policing. Because here is what I have learned about sexual liberation: It can only come about as the result of a just society. White supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism and capitalism—these are the root causes of sexual oppression. To free our sexualities and claim our most intimate freedom, we don’t just need more legal rights or the newest sex toy (although both are nice). Instead, we need to end racial capitalism and build a just economy. We do this by supporting the activists and organizers fighting to get us there.

I know that’s not exactly the usual “sex advice,” but I am far from the first one to assert this. In fact, I’m just taking us back to basics. We all know about Stonewall and the role that trans women of colour like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera played in kicking off the modern LGBTQ2S+ movement. But do you know about the revolutionary nine point list of demands that Rivera and Johnson released in 1970 through their short-lived organization, Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries?

The first point in the S.T.A.R. manifesto is as relevant today as it was then: “The right to self-determination over our bodies, the right to be gay anytime, anyplace; the right to free physiological change and modification of sex on demand; the right to free dress and adornment.”

Hell, yeah. But what’s striking is how much of their militant political stance has been abandoned by mainstream LGBTQ2S+ movements. The final demand in the manifesto was for “a revolutionary people’s government where transvestites, street people, women, homosexuals, blacks, puerto ricans, indians and all oppressed people are free and not fucked over by this government who treat us like the scum of the earth…this government that spends millions to go to the moon and let’s poor American starve to death.” They signed it, “POWER TO THE PEOPLE.”

S.T.A.R. and other organizations of the era, such as Vanguard, were revolutionaries. They understood their gender and sexual liberation as inherently connected to radical, anti-racist, anti-poverty, anti-police and feminist movements. Sexual liberation, as it was imagined by Johnson and Rivera, had more in common with the Black Power and Puerto Rican independence movements than with marriage equality.

“Many of our queer and trans elders have always known that sexual liberation depends on everyone’s liberation.”

Today, who even says “sexual liberation”? No one—because its aims have been watered down into individualistic pablum about choice and preferences. This includes how the idea of sexual consent is reduced to two people making a private decision. That is not how sex works. Sex has been trivialized as a personal playground, miles away from dusty political debates. But sex is not Narnia, it is about structural power. (I know, sounds sexy right?) Access to sexual pleasure, identity and connection is political. It is about who gets to live and be loved; whose sexuality is seen as beautiful and whose is seen as sick, criminal or a fetish; who is free to say “yes” with joy and “no” without fear; who gets competent sexual health care and who is on their own.

Many of our queer and trans elders have always known that sexual liberation depends on everyone’s liberation. It means a world where the values of exploitation, extraction and violence are replaced with self-determination, democracy and collective liberation. And that will take a revolution. In this series, I’ll be talking to queer and trans activists, thinkers and organizers about their fight for social and economic justice, and I’ll be thinking through the connection between justice and sexual desires, bodies and communities. Join me as I pull back the sheets to reveal the links between protest and pleasure, between organizing and orgasms.

We’re starting the series by looking at ableism—or “the bane of my motherfucking existence,” as Patty Berne puts it in this 2017 interview. In that same interview, the late, great Stacey Park Milbern, one of the founders of the disability justice movement, describes ableism as “a system of oppression that favours able bodiedness at any cost, frequently at the expense of people with disabilities.”

Ableism encompasses everything from oppressive laws that deny disabled people rights and the privatization of services and health care to the disrespect and desexualization of disabled people. If you want to understand what’s done to humans in the name of ableism, consider how a wealthy white woman like Britney Spears could be stripped of legal personhood in front of millions of people, in significant part because of her mental health—then imagine the impact of ableism on everyone else, with less privilege, behind closed doors.

Ableism is why, if your body or mind interfere with (or even just slow down) profit-making, capitalists don’t want it. And to be clear, this is an issue relevant to everyone, including those who don’t currently identify as disabled. As disabled activists frequently point out: Most people will be disabled at some point in their life whether from aging or illness or accident. In the U.S. and Canada, disabled people can be paid less than the minimum wage, be warehoused indefinitely in institutions (or live in fear of it) and be denied medical care.

Ableism is evident in governments’ obsession with and attempts to regulate the sex and love lives of disabled people (and we’re not even getting into the history of eugenics and forced sterilization here). Have you ever heard the saying “There’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation?” That phrase was famously uttered by Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in 1969 as his government pushed for the decriminalization of homosexuality, among other amendments to the criminal code. Turns out, he didn’t mean disabled people’s bedrooms. Most governments in the U.S. and Canada will cut or eliminate disabled people’s income supports if they are in a common-law relationship or married. And bear in mind that being married is one of the few ways for disabled people to get access to health insurance.

When it intersects with white supremacy, ableism is where we get the idea of the “superhuman monster,” the dangerous disabled or mad person of colour who must be contained or eliminated. Consider how many interactions between police and a racialized person in mental distress end with fatal violence perpetrated by police: In Canada, Regis Korchinski-Paquet, Chantel Moore and D’Andre Campbell are recent examples, but the list goes on. And according to a 2016 report by the Ruderman Family Foundation, a U.S. disability rights group, half of all people killed by American police are disabled.

So what’s all this got to do with sex? I spoke to Berne and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, the writer, teacher and author of Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, about how ableism ruins sex for everyone—whether they have a disability or not—and what we can do about it. As Berne puts it, “Ableism ruins sex because it obliterates the sexualities of people with disabilities. But it also restricts able bodied people from being creative or different; it says that unless you’re normative, you can’t fuck.” In other words: Ableist attitudes that designate only a narrow range of bodies as desirable and attractive affect all bodies—if you don’t meet a very, very limited (white, thin, non-disabled, young, etc., etc., etc.) standard of beauty, then you are not worthy of sex or love. But as Berne said in another interview “people with non-normative or non-conforming bodies…we are hot—super hot in fact!”

Credit: Jesse Manuel Graves

Both Berne and Piepzna-Samarasinha talked about how ableism takes our human capacity for pleasure, then shames and punishes every body, mind and need that falls outside of “normal.” Ableism is why mental health issues, sickness and physical disability are always made out to be a disaster for sex, something to be hidden away so you don’t “ruin the mood” and kill your sexual attractiveness (it’s actually ableism that’s “ruining the mood”). “Normalcy” is a scam robbing us of everything rich and human about our sexualities, tricking us into believing that only typical minds and healthy bodies get the good sex.

“Disability justice is at the core of sexual liberation because it is a radical ‘fuck you’ to the standard of normalcy.”

I asked Berne and Piepzna-Samarasinha how we can resist ableism and free our wild, weird bodies, minds and desires. “Disability justice is for all people with bodies,” Berne says. “It’s not about crips alone, by any means.” Piepzna-Samarasinha adds that disability justice “is at the core of sexual liberation, because it is a radical ‘fuck you’ to the standard of normalcy.” In my own life, I credit Berne and Piepzna-Samarasinha and so many other brilliant queer disabled friends with teaching me why sickness, disability and neurodivergence can be a gift to sex, because they necessitate honesty, vulnerability and creativity. Speaking of creativity: If you’ve ever used a silicone dildo, thank the working-class, disabled Black man who invented them in the 1970s. Adaptation is for everyone!

Being honest about ones’ needs and rolling with adaptations to positions, moods and energy levels keeps sex raw, risky and authentic. We become conduits for the sexual magic of the unknown, not actors in someone else’s script. In “10 Principles of Disability Justice,” Sins Invalid, Berne’s performance project, imagines a radically interconnected world where we celebrate our vulnerable, imperfect bodies and “move together as people with mixed abilities, multiracial, multi-gendered, mixed class, across the sexual spectrum, with a vision that leaves no bodymind behind.”

Now that’s sexual freedom.

Disability justice is intimate and it is structural. So what does that look like in practice? It’s sex parties that are accessible and stigma-free across the spectrum of race, class, sexuality, ability and embodiment—and it’s an end to wars, police brutality and environmental racism that create so much illness and impairment. It’s celebrating “crip lust,” as Piepzna-Samarasinha describes it; the kind of heat generated when disabled people recognize and desire each other—and it’s ensuring that no one’s access to income or health care is dependent on their marital status. It’s taking a relaxed approach to leaky, unpredictable bodies and sexual mishaps—and it’s disabled people getting free from controlling and punitive institutions such as detention centres, locked-down psych wards and prisons.

And how do we get there? Here’s some guidance from Berne and Piepzna-Samarasinha on where to start: First, understand that resisting ableism means resisting all the systems that devalue and punish human difference, including white supremacy, capitalism and patriarchy.

Second, learn about the disability justice movement and its principles. Read the Sins Invalid disability justice primer, watch their performances, check out their erotic videos featuring non-exploitative hot crip sex and read the writings of disabled people of colour.

Third, assess disability in your own life. Are you disabled or neurodivergent, even if you’ve never used the terms? Either way, ask yourself: What would make it safer for you to ask for your needs to be met? Find out who is disabled in your family, community and lineage. Get connected to others and get organized. As Sins Invalid puts it: “No body or mind can be left behind—only moving together can we accomplish the revolution we require.”

In the next installment of Protest and Pleasure, Chanelle Gallant will explore why defunding the police is foundational to the flourishing of sexual safety and freedom.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra