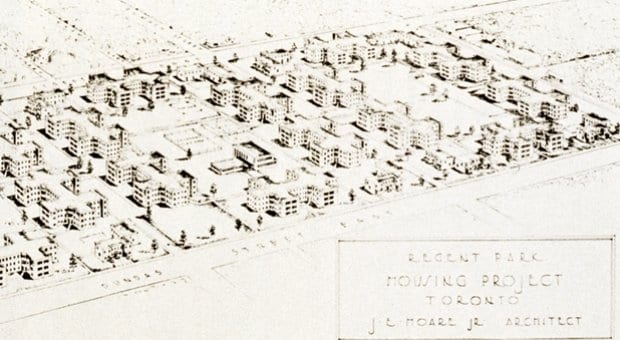

A 1947 plan for Regent Park based on American-style public housing. This drawing comes close to reflecting what was built in subsequent years. Credit: City of Toronto Archives

Development director Heather Grey-Wolf and her team at Toronto Community Housing Corporation, from left: Julio Rigores, Frozan Shaikhmiri, Abigail Moriah, Christine Burke, Wolf, Ilidio Coito, Jed Kilbourn and Kristy Wung. Credit: Adam Coish

Michael Creek moved into Regent Park as a TCHC tenant in 2000. He now owns his own condo and sees the area as a place with lots of potential. Credit: Adam Coish

In 2011, more than 54 percent of Regent Park residents reported a non-official language as their mother tongue. Maintaining this diversity is a key part of the city’s plan for the area. Credit: Adam Coish

Meri Perra, right, with her partner, Catharine. The couple lives near Regent Park with their two young children. Credit: Adam Coish

The creation of new high-rises means the population of Regent Park will jump from 7,500 to as much as 17,000 in the next few years. Credit: Adam Coish

Chris Klugman is the owner of the Paintbox Bistro in Regent Park. The restaurant is a for-profit social enterprise that opened in 2012. Credit: Adam Coish

The Paintbox mission includes training and career development for marginalized individuals, with a focus on those living in Regent Park. Credit: Adam Coish

Ask Torontonians to describe LGBT life in the downtown core and they’ll usually cite the several pubs and clubs that line Church-Wellesley Village. Then there’s nearby Cabbagetown, with its arts festivals and Victorian homes, known to house many a queer.

But Regent Park? Not likely to get a mention. And yet it’s not that much of a stretch.

Regent Park actually held the name Cabbagetown before the neighbourhood to its north claimed it in the 1970s. Today, the two bordering neighbourhoods are part of the same federal and provincial riding of Toronto Centre, a district that also encompasses the Village. And like the Village and Cabbagetown, queer people do live near and in Regent Park. That’s nothing new.

What is new is the face of Regent Park. And soon, many hope, its reputation.

Often considered an undesirable neighbourhood — and, to some, a neighbourhood of undesirables — Regent Park is gearing up for a very different identity.

Lacklustre towers are giving way to stylish condominiums. Businesses have at long last moved in. Amenities such as parks and pools are to make up Regent Park’s new face. The changing streetscape comes courtesy of a redevelopment plan for the downtown-east neighbourhood.

“Revitalization, in addition to creating new buildings and amenities, is a catalyst for change beyond the physical infrastructure,” says Heather Grey-Wolf, development director for Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC).

The Regent Park revitalization began in 2006 by way of a public-private partnership between TCHC and The Daniels Corporation. Its end goal is a mixed neighbourhood that closely reflects other parts of the city.

TCHC estimates the revitalization will be complete within 10 to 15 years, should they get approval for the rezoning of the remaining phases. The organization anticipates a final report from the city will go forward at the East York Community Council on Nov 19. TCHC expects a final decision on the application at city council on Dec 16.

Regent Park’s population is set to jump from 7,500 to between 12,500 and 17,000 by the project’s end. Estimates price the project at just less than $1 billion. TCHC will invest about 60 percent of the total expected cost through bond funding and equity. Government grants and rebates will cover about 13 percent, while proceeds from the condominium sales will pay for the remaining balance.

It’s a big quote for a big job.

The history

Regent Park is one of Canada’s largest and oldest social housing projects. Its construction began in 1948 and carried on until the end of the 1950s. Bounded by Gerrard, Shuter, River and Parliament streets, Regent Park’s design saw it physically turned inward. This separated the neighbourhood from Toronto’s busy downtown, but a lack of streets and pockets of unused space left Regent Park vulnerable to criminal activity and unable to reap the benefits of city life.

Even with the revitalization well underway, worries about crime haven’t vanished. In fact, some academics have expressed concern that the mixed-income model is creating an “us versus them” dynamic they believe has resulted in crime and violence in the neighbourhood.

But that could change. Crime prevention methods like the installation of video surveillance cameras and enter-phone systems are part of the revitalization project. Streets in Regent Park will be wide and well lit. Furthermore, there are proposals calling for the addition of three new streets to the area.

“By connecting Regent Park to the surrounding neighbourhood, the community is becoming a destination in Toronto,” Grey-Wolf says.

The construction of new high-rise and mid-rise buildings makes up most of the current third phase of redevelopment. On Sept 20, the first residents moved into 230 Sackville St, a 10-storey building containing 105 rent-geared-to-income units and 50 affordable rental units. It’s the newest rental building in Regent Park and residents should fully occupy it later in the fall. Replacing old towers and building community amenities were the focus of the first two phases. “These new amenities serve as a gathering point for residents of Regent Park and the nearby neighbourhoods,” Grey-Wolf says.

These new amenities include a daycare centre, a park currently under construction, the Regent Park Centre of Learning, Regent Park Employment Services and Daniels Spectrum, an arts-and-culture hub housing various local organizations. TCHC has also teamed up with Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment to see the building of a multipurpose outdoor sports field and in June launched the Regent Park Farmers’ Market in partnership with The Daniels Corporation.

Unfortunately, this grand-scale project meant the relocation of many Regent Park residents. As a result, TCHC promised those forced to relocate new homes built as part of the redevelopment. That’s 2,083 rent-geared-to-income housing units. Of those units, however, 266 are located outside Regent Park, on Carlton, Richmond and Adelaide streets in the east downtown. Sales of 5,000 planned market condominiums will cover the costs of the replacement units. Profits will also go toward building several hundred affordable rental units.

Some have labelled what’s going on in Regent Park displacement, noting that the mixed-housing model has often meant pushing the poor to the margins. This fear predates the commencement of construction.

For instance, Rita Daly wrote the following in the Toronto Star on Feb 12, 2005: “As the agency forges ahead with its project, fully endorsed by city council earlier this month, there are those who fear Regent Park’s makeover may be yet another regrettable experiment in the city’s history of social housing. A group of academics and social activists criticize it as an enticing land grab for private investors, at the same time as it slashes the number of low-income apartments and displaces the working and subsidized poor.”

Many Regent Park tenants would certainly welcome more low-income housing options. The 2006 census showed that the average income for private households in Regent Park was only $35,656, with about 41 percent making less than $20,000 a year. By comparison, the average income for households in Toronto was $80,343.

And it isn’t all roses for those who will ultimately upgrade their housing situation. Life in a construction zone and the resulting temporary loss of facilities has naturally burdened those living in the neighbourhood. To that end, TCHC created a social development plan for Regent Park.

The plan guides the process for addressing community needs. The principles of equity, equality, access, participation and cohesion are its building blocks. Equity is specifically defined as “the fair distribution of resources, free from discrimination on the basis of age, disability, gender, socioeconomic background, race, ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation.”

The plan does not outline any points to better the lives of queer residents in particular, but that could change in the future.

“It is important to note that the social development plan is fluid so that it works with the community as it changes and can respond to the needs of populations that are underrepresented,” Grey-Wolf explains.

Regent Park is on the path to transition from a last resort of sorts to a legitimate, viable option.

The people

The story goes that when gay men move in, gentrification shortly follows. That may be the case, but while gentrification is new to Regent Park, gay isn’t.

Take Michael Creek. Since 2000, the 55-year-old Creek has lived in Regent Park — first as a TCHC tenant and since 2010 as the owner of a brand new condo unit.

Creek is the director of strategic initiatives for Working for Change, an organization that advocates for employment opportunities for those marginalized by poverty and mental health issues. He experienced financial hardship firsthand, from 1993 to 2008.

“I have a lived experience of living in poverty as a gay man,” he says.

For Creek, that meant going back into the closet and staying there for years after his move to Regent Park. He says he did so for safety reasons, because back then it didn’t feel like an environment that was welcoming to LGBT folk.

“I felt marginalized,” he says. “I’d lost my connection to the community… You don’t go to Church Street anymore when you’re poor. You can’t afford to do the socializing.”

Creek says the reality for queer people living in poverty is that they feel isolated because they’ve lost their ties to the larger LGBT community. The redevelopment is, in his opinion, going to make queer people in Regent Park feel less marginalized in their neighbourhood.

To Creek, the mixed neighbourhood model is “the only way to do housing that involves social housing.” He believes the new market condos and TCHC buildings look so alike that the average person won’t be able to tell who’s living where.

The revitalization has also brought an extra level of comfort for Creek in terms of safety. “Where I used to live, I used to lock my door and barricade it,” he says. “Now I often forget to lock my door.”

“There’s a real sense of security,” he says, noting that people are staying outside longer, making it less likely that illegal activity will occur.

Despite the improvements, he wants to see more affordable housing options for low-income people. He also insists that TCHC not push out those very people.

“It’s important that people get the choice of where they want to live,” says Creek, who believes a plan should be in place for those wanting to return to Regent Park who have been relocated to other east-end neighbourhoods.

The Regent Park choice is a no-brainer for Creek. “It’s a community that has a lot of potential,” he says. “I see myself living there until I’m very old.”

Creek says this despite admitting that instances of homophobia do still occur in the neighbourhood and that he would like to see programs that champion LGBT causes, like access to education, included in the redevelopment plans.

But he’s instead got an eye on the positives, like the increasing number of queer folk moving into the neighbourhood now that they have the opportunity to purchase condo units.

As they move in, Creek, who is no longer closeted, is enjoying the freedom of being out.

“I feel quite queer in Regent Park now.”

Suhail Abualsameed is the newcomer community engagement coordinator for Sherbourne Health Centre, a 10-minute walk from Regent Park on Sherbourne Street between Carlton and Gerrard streets. He runs Express, a Supporting Our Youth (SOY) program that since 2002 has, according to its website, supported “youth between 16 and 29 who are immigrants, newcomers to Canada, refugees, refugee claimants and non-status queer and trans youth.”

Many of the program’s participants come from countries where LGBT lifestyles aren’t safe or legally permitted. Abualsameed says living in these homophobic and transphobic cultures has had clear effects.

“Issues of depression and other mental health problems do come up a lot,” he says.

Life in Toronto by comparison?

“They all say it’s better than being back home,” he says. “There are challenges, but at the end of the day they would say they’re better off here.”

The Express program does not collect information on demographics so as to provide a trusting environment for participants. Even so, Abualsameed believes that Regent Park’s proximity means some of its residents are taking part.

It would certainly make sense, considering the neighbourhood’s makeup, which consists of a large immigrant population. According to the 2011 census, 54 percent of Regent Park residents reported a non-official language as their mother tongue, with the top five languages being Bengali, Tamil, Mandarin, Vietnamese and Cantonese.

For his part, Abualsameed isn’t worried that the post-redevelopment Regent Park will be less inviting for LGBT immigrants.

“It might be a different demographic in terms of class and wealth, but that doesn’t necessarily mean homophobia and discrimination.”

Meri Perra, 36, lives with her partner and two young children in the Oak Street Housing Co-Operative, located near River and Dundas streets. Perra, who is a freelance writer, has lived in the co-op for seven years. Although it’s just outside the Regent Park neighbourhood, she says, “it’s not the same community.”

“We don’t have a landlord,” she says. “We’re more in control of our housing.”

In a matter of years, many in Regent Park may be able to say the same. Regent Park tenants have first crack at buying the new condo units when they go up for sale. For low-income households, however, that may not be a likely reality. Even so, there are some options.

Two down-payment assistance programs funded by the provincial and federal governments as part of the new Affordable Housing Program are in place in Regent Park. Tenants may be able to purchase condo units with the help of the Foundation Program, which provides a second mortgage of up to 35 percent of the purchase price for those who are able to support a first mortgage of at least 65 percent through employment income.

There’s also the down payment assistance program (known as Boost), mostly accessed by those not already living in Regent Park. This program provides up to 10 percent of the unit purchase price for those earning moderate incomes.

Perra supports this mixed neighbourhood model. She appreciates the diversity that makes Regent Park stand out from much of the rest of the city.

“It is nice for us as a queer couple to be in an area that is racially and class diverse,” she says. “It makes a lesbian couple look less interesting.”

An air of acceptance or indifference is generally what Perra and her partner get from locals when walking hand-in-hand. “We wouldn’t want to live in a place where it wasn’t like that,” she says.

Still, she notes that nothing about the redevelopment “looks queer.” Even so, her family plans to stay put. “We’re happy here,” she says.

Several local gems — the nearby Riverdale Farm, libraries and drop-in centres — keep her children entertained. But Perra is most excited about one new addition.

“The Regent Park Aquatic Centre is beautiful,” she says. This indoor pool facility cost about $15 million and opened in October 2012. Equipped with such features as a waterslide, a diving board and a Tarzan rope, it’s been a hit with the community. The centre also has unisex changing rooms with many cubicles, providing a much more welcoming environment for trans people while also affording families the privacy to change together.

The aquatic centre replaced Regent Park’s aging outdoor pool. For Perra, that’s about the only letdown. “You gain this shiny new place, but this community landmark that is loved by so many is gone.

“Everything is going, but some things were good,” she says.

The politics

The thing about change is that sometimes you have to sacrifice the good to get rid of the bad.

“Regent Park needed to change,” says Bob Rae, a former member of Parliament for Toronto Centre from 2008 until 2013. “The status quo was not sustainable, and there needed to be change. It was just becoming too much of a closed community.”

Unfortunately, the physical characteristics of the neighbourhood at times led to crime waves that largely defined it. Rae says the federal government could improve the situation if it responded effectively to the issue of addiction; he claims police have told him that tackling addiction would lead to an overall decrease in crime in the neighbourhood. Despite this, he guarantees “efforts are constantly being made.”

Last June, Rae announced he would be stepping down as MP. While he will soon no longer be the political voice of the people of Regent Park, he says he will continue to be active in the neighbourhood.

“Representing the people of Regent Park has been an honour.”

It’s hard for many in the neighbourhood to remember a time when Ward 28 Councillor Pam McConnell didn’t represent Regent Park. She’s been a councillor in the neighbourhood since 1994, making it through amalgamation and redistricting, and says change is what the community wanted.

“The Regent Park redevelopment was the vision of Regent Park residents,” she says.

Many residents attended consultation meetings so as to have their say in what they wanted out of the revitalization. According to McConnell, big names like Tim Hortons and FreshCo by Sobeys are expressed desires of Regent Park tenants. “It’s a symbiotic relationship between residents and businesses,” she says.

She believes that’s crucial because the redevelopment is not just about “changing the bricks and the mortar” or “housing different types of people.” It’s also about employment opportunities. Street-level commercial space will be part of many of the new buildings, with well-established businesses getting priority.

According to TCHC, the revitalization has created approximately 650 jobs for local people in construction, retail and other areas. It’s an important development for the neighbourhood, as the 2011 census revealed that 58 percent of residents reported they fell in the working age group (25 to 64 years old).

For McConnell, it’s a clear sign that the stigmatization of Regent Park tenants as work-shy is misplaced. “When Regent Park people, both young people and adults, are given opportunities for employment, they will take them,” she says.

McConnell hopes they’ll take all the opportunities presented to them with the revitalization. Those opportunities, however, could stand to be more plentiful for the queer community. Nonetheless, McConnell says issues facing LGBT people are a consideration as they fall “under the umbrella of human rights.”

And besides, McConnell says that the queer residents she knows in Regent Park tell her they feel comfortable living there. “I’m seeing the celebration,” she says, referring to the rainbow flags she saw displayed throughout the neighbourhood on Pride weekend. “I think there is a huge acceptance.”

The business

“There does seem to be broad acceptance,” says Chris Klugman, owner of the Paintbox Bistro, a for-profit social enterprise restaurant, café, food-based incubator and catering company located at the corner of Dundas and Sackville streets.

“We get a pretty significant gay clientele,” he says.

Most come from further east in the city, but many are Regent Park residents themselves. The guys, especially, have adopted the spot as brunch-date central. Many Paintbox employees are also queer. “I can’t explain that,” Klugman says. “We don’t hire based on sexual orientation.”

Maybe it’s the welcoming environment: the place has a rainbow theme going on inside that screams gay-friendly.

The Paintbox is about more than providing a hip dining experience. It’s a certified B-Corp (short for benefit corporation) — a designation for companies that use business to bring about social and environmental change.

That change is happening at the local level. “Our mission is the training and career development of marginalized individuals, with a specific focus on our neighbourhood,” Klugman says.

Recently, a grant sponsored by Dixon Hall Employment Services, administered by the City of Toronto Employment and Social Services and provided by the Government of Ontario, saw to the training and hiring of 13 new “Paintboxers.”

Ontario Works sent out a mass email informing those in the Regent Park area about a job fair at George Brown College, where Klugman is a sessional professor. The chosen candidates were able to attend the school for one semester of culinary training, with tuition covered. Two weeks of training at the Paintbox followed, after which they became regular employees. “It’s not a co-op program,” Klugman clarifies. “Everyone is paid.”

The Paintbox opened in September 2012. Klugman says the business has done “fine,” but, with no outside investors or equity partners, he admits it relies heavily on community support. Although it’s been only a year, Klugman believes he’s got plenty to celebrate. “In terms of our social mandate, we’re already a phenomenal success.”

But there have definitely been hurdles.

“It’s really been challenging to get outside communities to see this as a destination,” says Klugman, who wants 15 new restaurants to open in Regent Park so that people recognize it as a go-to neighbourhood for dining. The Paintbox isn’t the first restaurant he’s opened, and he says it’s been his experience that people prefer eating out in areas where there are blocks of restaurants, like in the Village.

“It’d be much easier if we were on Church Street,” he says.

Reality being what it is, he issues a challenge: “How do we get Church Street to come here?”

How? By getting the redevelopment right. But based on precedent, that won’t be easy.

Major neighbourhood overhauls have been attempted elsewhere, and yet success stories do not abound.

For example, there was the clearing out of East London to make way for the Olympic Village for the 2012 Summer Olympics. With the games over, developers started converting the area to a residential district. Despite promises that the new homes would be affordable for former residents, the reality is that the redevelopment displaced thousands.

The moving in of big-name retailers hurt small businesses, to the point that many closed up shop for good. The Games did result in the creation of new jobs, but most of those ended when the Olympics did. The redevelopment created long-term jobs as well, but those pale in comparison to the jobs that were lost when the factories were torn down to build stadiums.

Closer to home, there’s also cause for concern. In recent months, revitalization plans for Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside have drawn the ire of anti-gentrification protesters. They have picketed restaurants and committed acts of vandalism. Those protesting claim the social-mix model is not a good fit for the neighbourhood, often called “Canada’s poorest postal code.”

However, several differences exist between these examples and Regent Park. The most glaring is that the Regent Park revitalization is not centred around one major event — that is, the Olympics — and is therefore more socially responsible in nature. In Toronto, developers kept tenants informed about the redevelopment process, thus avoiding public uproar. Furthermore, few businesses existed in Regent Park before the redevelopment, and those that did were not major job creators.

And while it’s true that the prices on those market-rate condos make owning one unlikely for most current residents (many units are selling for more than $325,000), TCHC does have a standing commitment with tenants to provide them with replacement units. But the fact that a few hundred of those units are located outside Regent Park is concerning. That’s displacement, and such happenings could call the integrity of the whole revitalization into question.

In Creek’s opinion, TCHC has justifiably avoided that scenario so far. “In the case of the redevelopment, I think they’ve done a pretty good job in engaging and communicating with people.”

A crucial part of the revitalization strategy is successfully reaching out to those who didn’t live in Regent Park pre-redevelopment. Already there are signs that this is the case.

“Regent Park has seen an increase in visitors from all over the city, as well as tourists from all over the world,” Grey-Wolf says.

They’re welcome to visit, but don’t expect Regent Park to give up its identity. “My hope is that we do maintain a distinctive character as time goes on,” says Klugman, who’s happy to be “a small part of a much larger picture.”

That appears to be the case for now. “To me, the spirit is still there,” Perra says, noting that spirit is one that’s increasingly welcoming of LGBT folk.

Good, because they’re coming.

Abualsameed claims he knows many queer people who moved to Regent Park because of the redevelopment. “The revitalization is completely changing the face of the neighbourhood,” he says.

“The whole core of the city is becoming more and more a place of celebration and a gathering place for the queer community,” Rae says. “I think we’re going to continue to see that happening in Regent Park.”

As changes come to Regent Park, so too might the evolution of a mutually beneficial relationship for the neighbourhood and the LGBT community.

“I think that it will be a community that will be very welcoming to the queer community,” McConnell says. “A community where the queer community will feel very much at home, and, in fact, the queer community will be great, great contributors to the sense of Regent Park as a place for everyone.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra