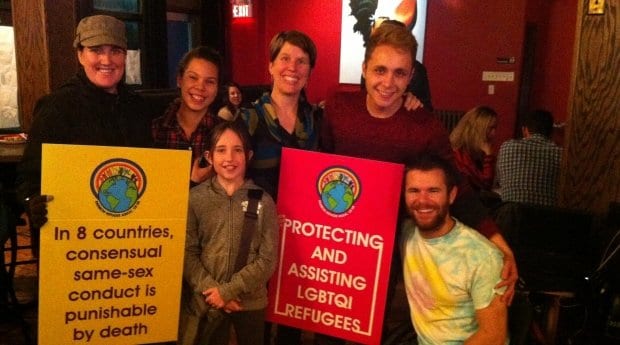

Members, and sponsors, of the RRNS. Credit: Rebecca Rose

A tall, handsome man stands at the microphone at the front of The Company House. “Are you nervous?” he asks. “I am.”

He laughs and begins to tell a bar full of people, in a city he had never heard of until a year ago, about his experience of being a gay Iranian refugee in Halifax.

“Back home, being gay is punishable by death. So I had two options, and one was worse than the other. Death was worse — to die because I’m gay — but to get out of country and see what would happen was also bad. So I chose the bad way, not the worst.”

Navid knew he was gay by his mid-teens. There is no Farsi word for gay, but he heard the word “homosexual” for the first time when the former Iranian president was questioned about the country’s persecution of gay Iranians while visiting California. Navid excitedly searched the internet and found chat rooms for gay Iranians and met his first gay friends. He was crushed to discover that being gay was a capital offence in his country. Living in constant fear, Navid attempted to take his own life on four separate occasions but could never follow through.

It was the arrest of several gay friends that led Navid to leave Iran for Turkey and seek refugee status based on sexual orientation. He told his family he was a political refugee.

In Turkey, Navid met with a UN psychologist for three hours of questioning to establish that he was, in fact, gay. He met his boyfriend, also a gay Iranian, and they decided to link their applications.

Navid suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder from the two years he lived in Turkey, not knowing what would happen to him. As refugees, they weren’t able to work legally, and Navid worked under the table at a factory. The day he found out his application had been accepted, he was en route from another factory outside of town.

“You cannot believe the feeling,” he says. “It was like flying.”

The pair knew people who had moved to Toronto but were told it would be quicker to move to Nova Scotia. “I said, ‘Okay, if it is one day faster I will go.’ Our situation was so bad in Turkey,” he says. Navid describes zooming out on Google Maps to locate their new home, Halifax.

Navid and his then boyfriend arrived in Halifax in 2013. They were the first two people sponsored by the Rainbow Refugee Association of Nova Scotia (RRANS).

Since its inception in 2011, RRANS has privately sponsored four gay refugees from Iran — all men. The third refugee arrived in December; his soon-to-be roommate was to arrive in November but is stuck in a bureaucratic quagmire and likely to arrive in January. RRANS has also assisted the Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia (ISANS) with four other gay refugees, most recently a lesbian couple from Somalia via South Africa. RRANS has only once seen a lesbian couple on the list, and they were quickly sponsored elsewhere.

Hugo Dann, a prominent Halifax gay activist, is one of the founding members of RRANS. Dann became passionate about working with gay refugees after hearing of Alvaro Orozco, who was to be deported back to Nicaragua because Canadian officials did not believe he was gay.

In 2011, David Pepper, the founder of the LGBT refugee support group the North Star Triangle Project, gave a presentation to a dozen Halifax activists about private sponsorship as part of his 21-city speaking tour. Soon after, Dann, Corrie Melanson (now a RRANS board member) and Evelyn Jones of ISANS joined forces, and their first fundraising attempt was a bake sale that raised $350.

By fall of 2012, RRANS consisted of Melanson and new board member Kyle DeYoung. DeYoung remembers the date of the meeting, Oct 8, when he told Melanson, “We have to set a goal, and if we don’t meet it, then we can just disband the group. We can focus on advocacy or we can focus on sponsoring someone.” They chose sponsorship, “with the idea that that would lead to greater advocacy,” DeYoung says.

Private sponsorship costs approximately $11,000, according to RRANS, and the two set out to raise $6,000 by the end of the year. DeYoung still doesn’t quite understand how it happened, but in just two months, RRANS had raised $6,500.

The pair were disheartened when they learned that the first refugee they had selected couldn’t arrive for 48 months because of government regulations. (The group is currently working with Halifax NDP MP Megan Leslie to lessen the waiting period.) Neither Melanson nor DeYoung knew where they would be in four years.

Going forward, RRANS decided to sponsor only refugees on the (then) new “visa office referred” (VOR) list. The VOR program, launched in 2013, matches refugees — from Burma, Bhutan, Eritrea, Iran and Iraq — identified by the United Nations high commissioner for refugees (UNHCR) with private sponsors. Refugees on that list have already had criminal background and medical checks, for example, and are waiting for sponsorship money. The program provides six months of income support; the sponsoring group must provide an additional six months’ support, as well as approximately one year of social and emotional support.

Navid and his boyfriend arrived in November 2013. RRANS chose to sponsor a couple because the VOR refugees receive only $691 a month. Couples can combine their government funding and split a one-bedroom apartment. DeYoung says they once saw a transgender person on the VOR list, but RRANS couldn’t afford sponsorship because the person was single. RRANS would like to see increased government funding for both government-assisted and privately sponsored refugees.

Members of RRANS, as well as members of the media, met Navid and his partner at the airport. DeYoung says the group asked journalists not to take photos or video, but the couple’s image appeared on TV and the front page of the newspaper.

Two days later, the men were shopping in a Sobey’s grocery store when several other shoppers welcomed them to Canada. Confused, Navid finally asked a man how he knew. The shopper bought them the paper with Navid’s laughing face under the headline “A Gay Refugee Can ‘Be Free.’” He spent the rest of the shopping trip trying to hide his face, scared that someone might want to hurt them for being gay. It was months before he would believe that a straight person could support the LGBT community.

“We feel more safe with the Rainbow Refugee group; they are like our family,” Navid says. Members of RRANS found the couple an apartment, collected donated household items and helped them navigate bills, find jobs and get into school. Navid is currently enrolled at Nova Scotia Community College working toward an information technology diploma.

Beyond RRANS, Navid has found community in Halifax. His immigrant friends, who don’t know he is gay, often ask him how he has so many Canadian friends. “It’s a secret,” he replies.

He goes out to a local gay bar, Menz and Mollyz, and this year marched in his first Pride parade. Navid insists that the gay community here is not that different than Iran’s underground gay community: “It’s the same drama here,” he jokes.

RRANS is currently in the midst of a funding drive, where an anonymous donor will match every dollar given before January 2015. They have already raised $5,600.

“This is a stop-gap measure,” DeYoung says. “Rainbow Refugees for me is not the ultimate goal. The ultimate goal would be to have acceptance worldwide, so that we wouldn’t have to sponsor people.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra