In the spring of 1990, just after Gareth Kirkby moved to Toronto from Guelph, Ontario, he saw a gay man getting beaten as he stepped off a streetcar on College Street. Not long after that, he was walking on Church Street just north of Wellesley when he witnessed a gay man being chased by a group of people. Desperate for help, the man flagged a passing cop car.

“The cop car pulled over and talked to him, and then the cop drove off and left him to the bashers. That was the point where I decided I had to do something about it.” He soon connected with a small group that had been meeting informally, that would become the Toronto chapter of the new and radical organization Queer Nation.

Made up of a collection of small groups in cities across North America that all arose at roughly the same time, Queer Nation was born in 1990 and took its cues primarily from New York’s ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), a highly visible organization that emerged out of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s.

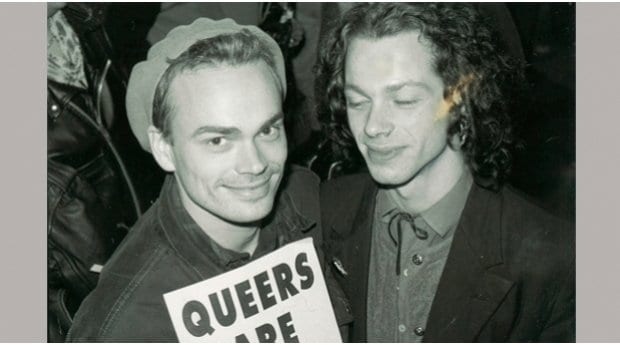

At a time when queer issues were still largely invisible and the legal system refused to take gaybashing seriously, members of Queer Nation took matters into their own hands. They postered the neighbourhoods of known bashers to let people know who was living among them; they organized late-night patrols to offer protection when they knew the police couldn’t be counted on. It didn’t take long for the mainstream to start noticing.

“The very fact the queer community organized late-night control to make up for the fact that the police wouldn’t take control did start something that eventually led to the justice system moving forward,” Kirkby says. “The system doesn’t like it when communities realize that they have to protect themselves.”

“I think at the time, it was very purposefully in your face,” says Queer Nation member David Walberg, “both in terms of within the community and for the wider world, to use a word that was brash and radical and, at the time, new for people. Even though the word queer was used for many decades before that, it felt like the first time it had been used en masse by a group of people to self-describe.”

Controversy about its use, even within the movement, was seen as furthering the goal of shaking people up and keeping them on their toes. It was unapologetic and demanding. “It was part of the appeal of using a word like queer at the time,” Walberg says.

Members of Queer Nation were less concerned with specific issues and more interested in making as big a scene as they could, with actions focused on letting the public know that queer people were in their midst and weren’t going away. There were marches and rallies and kiss-ins in public parks and straight bars. One of the largest demonstrations took place in the Eaton Centre, a large mall in the heart of downtown Toronto.

“The Eaton Centre [action] put some queer visibility into the picture by having dozens of queer couples start making out in front of all these shoppers and giving them something to think about in terms of the people who were around them.”

Paul Schindler, editor-in-chief of New York City’s largest queer publication, Gay City News, says he’s surprised the word queer is still up for debate in light of the history of Queer Nation. “It has been more than 20 years since people embraced that word publicly in a big way.”

Schindler was involved in Queer Nation in NYC and participated in similar events, all designed to take advantage of ACT UP’s momentum and continue to increase queer visibility. He says that, in some ways, society has come to a standstill in the absence of radical groups like Queer Nation.

“It’s ironic to me, all this time later, the whole world is talking about [college football player] Michael Sam kissing his boyfriend when they found out he was being drafted in the NFL. All this time and people are still very, very nervous about it.”

In spite of lingering attitudes in mainstream culture, the changes Queer Nation spurred lived long after the groups themselves fizzled out. Walberg says the speed at which change happened was remarkable, especially to the people within the movement who were used to being, at best, ignored entirely.

“Queer Nation was really of a moment,” he says. “Within a few years, we had relationship recognition that a lot of people never thought that they would see in their lifetime. It was happening very quickly in terms of media coverage. You started to see gay and queer people and issues and stories represented in the media where they had been really holding out on that.”

The group didn’t last more than a few years and the word it chose as part of its name has come in and out of favour in the years since, but the impact Queer Nation made on the North American consciousness is undeniable.

“It’s hard to keep that level of momentum up with any organization,” Walberg says, “but in this particular instance, we did start to see very quickly a big change in the response of mainstream society to gay rights.

Who’s Queer Now?

An Xtra town hall on identity, Wed, June 18, 6:30–8pm, Fountainhead Pub, 1025 Davie St

Can’t join us in person?

The town hall will also be simultaneously streamed live on dailyxtra.com from 6:30–8pm PST so viewers can watch and participate in real time, no matter where they are.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra