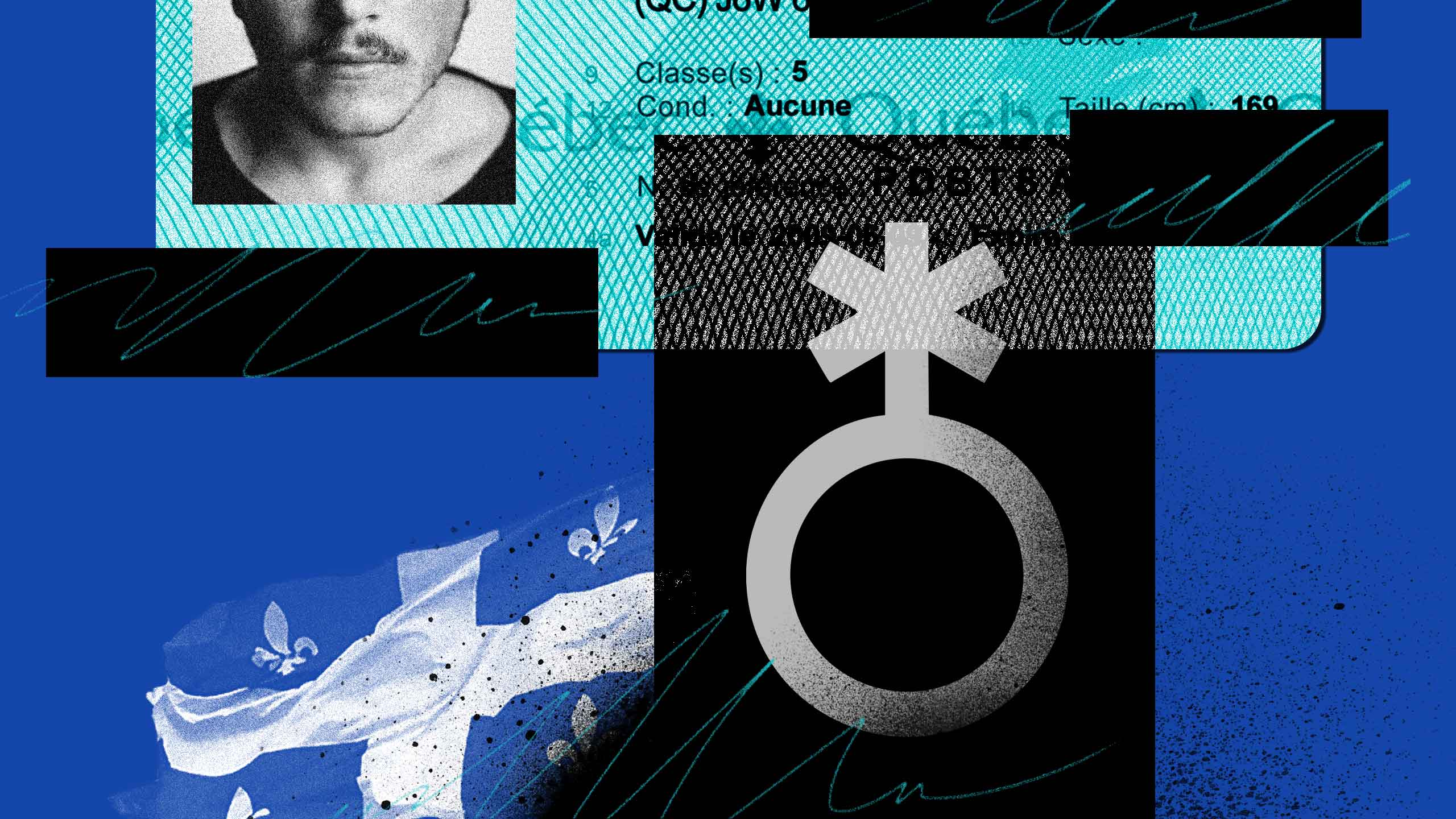

Last month, trans and non-binary folks in Quebec celebrated a rare win. After a years-long legal battle, the Quebec Superior Court ruled that a number of bureaucratic obstacles faced by trans and non-binary people—including processes related to legal name changes and official designations of sex—are unconstitutional.

The lawsuit was first initiated in 2014 by Canadian LGBTQ2S+ advocacy groups the Centre for Gender Advocacy. Other Canadian LGBTQ2S+ groups, including Egale, Gender Creative Kids and LGBT+ Family Coalition, were also involved. In a 58-page decision, the court removed barriers for people who want their legal identification to align with their gender identity.

Here’s everything you need to know about the landmark decision, and how the rest of Canada stacks up against Quebec.

What did the law say before this ruling?

In Quebec, a person is assigned a sex at birth—either “male” or “female”—and it is recorded on their birth certificate. For trans and non-binary folks, their gender identity does not correspond with that sex. That designated sex is used throughout one’s life in their interactions with the government. However, Quebec residents can change their legally designated sex if they meet a number of criteria set by the Civil Code, a provincial body of rules that make up the most fundamental laws of Quebec. The Code is unique to Quebec and works in conjunction with the federal Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Since late 2015, Quebecers have been able to legally change their gender from male to female and vice-versa on legal documents without medical or surgical requirements (beyond an affidavit from a medical professional). In 2016, this was extended to minors, provided they received permission from their parents or guardians. At this time, Quebec’s process for changing genders was seen as one of the most progressive and streamlined in the country. But within a couple of years, other provinces surpassed the progressiveness of Quebec’s process when they introduced new liberties, including the addition of a non-binary gender identifier in several provinces.

What did the plaintiffs argue?

The plaintiffs in the case took issue with a number of the restrictions associated with legally changing one’s sex that are created by the Civil Code’s criteria. They argued that they reinforce a binary gender spectrum by forcing, for example, parents to identify themselves as either “mothers” or “fathers” on their children’s birth certificates.

In its decision, the court ruled that this practice is discriminatory “because [it] oblige[s] non-binary parents to identify themselves as a mother or father.” The court gave the government until the end of the year to add more inclusive language to the official documentation for parents. They also made it possible for parents who have changed their names to update that information on their children’s legal documentation, which was previously not possible.

The plaintiffs also argued that assigning a sex to newborns based on their genitals is discriminatory. The court disagreed, saying that babies don’t have a gender identity and that the designation “provide[s] an important benefit to society.” It did acknowledge, however, that gender dysphoria is a legitimate and dangerous experience, and that the process to alter a legal designation of sex should be as streamlined as possible so that trans and non-binary people can easily acquire legal documents that match their gender identity.

Lastly, the plaintiffs argued that young people face unique barriers in finding adequate, trans-friendly health care and that discriminating based on their age is unconstitutional.

How does this ruling change the Civil Code?

Article 71 of the Civil Code allows people to legally change their designated name and sex if they meet the criteria set out in the Code. But as it stands now, there are no legal gender identities in Quebec other than “male” and “female.” The court ruled that this is unconstitutional and gave the government until the end of the year to develop more inclusive gender identities for non-binary people.

Before the ruling, documents like birth, marriage, civil union and death certificates also identified people via their names and sexes. Now, people can get these documents without having their sex on it.

Do any barriers still exist after the ruling?

Prior to this decision, only Quebec residents above the age of 18 could change their names and sex without submitting a declaration from a medical professional, which the plaintiffs called unconstitutional.

The court agreed with the plaintiffs to an extent and struck the obligation for minors between the ages of 14 and 17 to present an affidavit from a medical professional. Adults who want to legally change their sex have to come up with a statement from someone who has known them for at least a year to confirm that they are “serious” about their transition while children do not need to provide this. The court ruled that simply striking the need for medical professionals to affirm young trans and non-binary people would create a new imbalance between what adults need to do and what young people need to do.

The courts did not, however, come up with a solution to this problem, and again gave the government until the end of the year to rectify this.

The Civil Code also states that minors between the ages of 14 and 17 have to notify their parents if they intend to change their names, that parents can then object to that name change and effectively veto it. The court ruled that this practice is not discriminatory and it was upheld.

What does the ruling mean for non-citizens living in Quebec?

The court ruled that Quebec residents without Canadian citizenship deserve the same rights when it comes to changing their names and sex on legal documents. Previously, only Canadian citizens who have lived in Quebec for at least a year could do this; now, anyone can, as long as they’ve been a Quebec resident for a year or more. The court made this change effective immediately.

How does Quebec compare to the rest of Canada on gender and legal documents?

Policies differ vastly between each of the country’s 10 provinces and three territories, and the federal government has its own practices that must be navigated. People who want to change their gender and name have to apply through federal and provincial or territorial channels, since some documents (like passports) are issued federally while others (like health cards) are issued regionally.

Across all provinces and territories, it is no longer necessary for individuals to have undergone gender affirmation surgery in order to change their gender on legal documents. In some provinces, like Ontario and Manitoba, a fee of about $30 must be paid to the government to change one’s gender marker on legal documents, not including the cost of producing a new birth certificate, which can be an extra $25 to $30 in either province. That fee varies widely throughout the country: In the Yukon, it costs $10, and in New Brunswick, there is no charge at all. Many provinces still require people of all ages to have a medical professional sign off on their request for a gender marker change, including Ontario. In Manitoba, the government requires a letter from a medical professional and a notarized declaration that they want the process completed. Many provinces, including Manitoba, British Columbia, Alberta, Nova Scotia and Ontario, allow residents to have a gender-neutral marker (such as “U” or “X”) on their identification or allow them to remove gender from their IDs altogether.

With this new ruling, Quebec joins New Brunswick and Nova Scotia as the only provinces allowing non-citizens to change their gender on official forms.

How does Canada compare to the rest of the world?

Canada is considered to be fairly progressive on the international stage when it comes to trans people changing their legal names and genders—although, as many critics have observed, it still has a long way to go.

In the United States, identity documents like birth certificates and driver’s licences are almost entirely handled on a state-by-state basis. States like New Mexico and Colorado allow non-binary gender markers and have no requirement for surgery if people want to change their names and genders. Tennessee remains the sole state that bars legal changes of sex for any reason.

But more progressive models for ease of access to name and gender changes do exist. For example, the Greek parliament passed legislation in 2017 that allows trans people to change their legal gender on documentation freely and with no requirements. Anyone aged 17 or older can do so, while minors who are at least 15 also can, provided they have approval from a medical professional. This move gave Greece one of the most easily accessible name- and gender-change processes in the world, despite the fact that many queer rights battles are still being fought there; same-sex marriage, for one, is still illegal in the country (although civil unions are legal). Countries such as Iceland, Argentina, Denmark and Malta have similar policies that allow trans adults to self-determine their legal genders.

What comes next for Quebecers?

For Nour Abi-Nakhoul, the ruling marks an important victory that must be followed by more regions. Abi-Nakhoul is a Montreal-based writer and Xtra contributor who has been vocal about the importance of this historic ruling.

“I think there’s a lot more that Quebec could be doing,” Abi-Nakhoul says. “But it can be really disheartening to forcibly misgender yourself when dealing with government bureaucracy.”

But the ruling is not yet set in stone. In a Mar. 5 press release, the Attorney General of Quebec wrote, in French, that they would be asking Quebec’s Court of Appeal—that province’s highest court—to reconsider the provision laid out for Quebecers aged 14 to 17.

“The purpose of this supervision is to confirm the seriousness of the steps taken by the child, in their best interest,” reads the statement. “Indeed, it is important that the Court of Appeal rule on the constitutionality of one of the invalidated provisions.”

Although this ruling was an important step in Abi-Nakhoul’s eyes, she is hoping that Quebec—and the rest of Canada—continues this work by filling other gaps in its policies which negatively affect trans people, including those in its health care system.

“Language to refer to trans people is not the be-all of trans struggle,” she says. “There’s impulses to be like, ‘Now that we’re changing official language around this, trans people have rights.’ It goes a lot deeper than that.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra