Pierre Trudeau may have famously needed just one walk in the snow through an Ottawa blizzard to decide to retire, but long-time Vancouver city councillor Tim Stevenson’s walk in the sand actually started months ago.

“To be honest with you,” Stevenson tells Xtra Jan 9, 2018, on the phone from Maui where he’s vacationing with his husband, “I made a decision that I wouldn’t run again about a year ago.”

It’s a decision he says he shared at the time with Mayor Gregor Robertson and their Vision Vancouver colleagues, but decided to keep quiet until the next municipal election year dawned.

Sixteen years is a long time to sit on city council, Stevenson says now; at a certain point, we all need to realize when we’ve “run out of juice” and need to make room for a new generation of voices to lead.

“I am 72,” he points out, “and I’ll be 73 this year.”

With his husband, Gary Paterson, the former moderator of the United Church of Canada, already semi-retired, Stevenson says he’s ready to relinquish his council seat in time for the October 2018 municipal election, in part so the couple can travel and spend more time together.

Still, he wrestled with the decision for years, he says, and even contemplated retiring prior to the last election in 2014, though he’s glad he served one more term.

“I am really going to miss the work,” he says, reflecting especially on everything he has accomplished for Vancouver’s LGBT community in his five consecutive terms on council.

“As I look back, everything that I really wanted to see accomplished within our community I think has been done,” he says, “and I feel really good about it.”

Tim Stevenson helps open Jim Deva Plaza on July 29, 2016. Credit: Angelina Cantada/Xtra

Stevenson’s long road to politics started just a few years after he burst out of the closet as a gay man in 1975.

For years he had fought his sexuality and was consumed with the battle raging inside of him. It was like being “held underwater in the ocean for 30 years,” he says, drowning under the fear that he would never succeed at anything if people knew his true self.

Coming out was beyond liberating: “I just came blasting out of the ocean with my eyes wide open, gasping for air” and exploding with energy, he says.

And he knew he had to join the fight for gay liberation.

At age 32 he enrolled at the University of British Columbia and joined a small group of students that would one day become Pride UBC. Stevenson soon became president and started planning the group’s first Gay Week in 1980.

“Back then, there was an enormous amount of homophobia,” he recalls. Few people were out on campus and those who were faced regular harassment; homosexuality had only been removed from the list of mental illnesses in the US a few years earlier and Canada had yet to follow suit.

Stevenson says he was “absolutely convinced that I had to do my part for change.”

“That Gay Week really established us as known throughout campus,” he says, looking back on those early days of activism at UBC as his “learning ground.”

Those lessons would help carry him through the next decade as he worked relentlessly behind the scenes to build consensus within the United Church of Canada to ordain openly gay ministers. In 1988, the church finally agreed, becoming the first mainstream Christian denomination in Canada to welcome gays and lesbians as full members eligible for ordination.

Stevenson was ordained four years later.

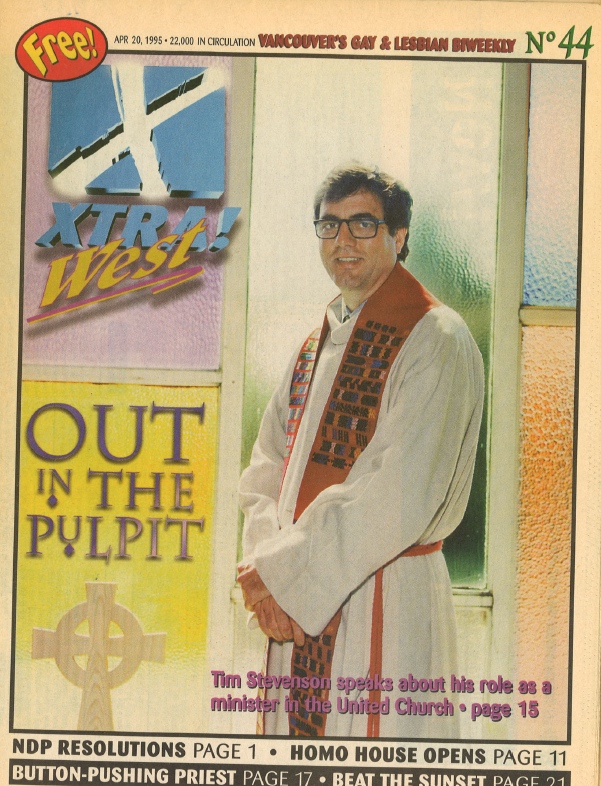

Tim Stevenson makes the cover of Xtra West in April 1995 as the first openly gay minister in the United Church of Canada. Credit: Daniel Collins/Xtra

“The impossible became possible,” Stevenson says. What looked initially like an insurmountable challenge slowly pulled within reach, as he confronted every door that seemed locked in his path. As humans, he says, we have to challenge those brick walls, we have to take those risks.

For Stevenson, the risks paid off and the doors slowly opened, one by one. “And I’m not a special person,” he notes. “I’m just ordinary Tim.”

It was his resilience in the church and his work as an international delegate in South Africa, when Nelson Mandela became president of the African National Congress in 1991 and then won the election in 1994, that brought Stevenson to the BC NDP’s attention, he says.

When the NDP approached him to run in the West End as an openly gay candidate in BC’s 1996 provincial election, Stevenson says he went on a silent retreat, as he often has in life to ponder big decisions, to contemplate the possibility of running for office. His answer was yes.

Until then, the church had been his calling, but he welcomed the shift as a new opportunity to make change. “I got into politics because, coming out of the gay community, I really saw the necessity of changing lives,” he says.

Stevenson again broke new ground in the 1996 election as one of the first openly gay men to win a seat in BC’s provincial legislature (along with Liberal MLA Ted Nebbeling).

Stevenson brought gay rights to the table every chance he could, especially when he got a seat in cabinet in 2000 — becoming the first openly gay person in Canada appointed to cabinet in any legislature.

Though he lost his seat as an MLA just a year later when the BC NDP was swept out of power, he soon set his sights on another level of government where he felt he could make positive change: city council.

Stevenson ticks off a number of accomplishments that he’s particularly proud of as he reflects on his 16 years on council, starting with the time he and lesbian COPE councillor Ellen Woodsworth convinced city hall to host a Stonewall commemoration in 2004, and invited gay activists to take over every seat in the chamber.

When the party Stevenson co-founded, Vision Vancouver, won a decisive majority in the 2008 municipal election on a shared ticket with COPE and the Greens, it ushered in an era of unprecedented support for LGBT initiatives in the city, he says.

From rainbow crosswalks to Jim Deva Plaza; from designating the Pride parade as a civic event to issuing Pride proclamations from the steps of city hall; from officially recognizing the historical significance of the Davie Village to Vancouver’s LGBT community in the city’s 2013 West End plan, to launching the city’s first LGBT advisory committee, Stevenson is proud of the progress he has helped foster in Vancouver.

That the advisory committee is now largely led by a new generation of LGBT activists is a very good sign, Stevenson adds.

Mayor Gregor Robertson proclaims Pride Week at city hall in 2012, with Tim Stevenson by his side. Credit: Shimon Karmel/Xtra

Part of his goal, Stevenson has told Xtra over the years, is to embed the LGBT community in the halls of power, to ensure that our voices are heard and our welcome is never rescinded.

“Never again will a political party say, ‘Oh well, we don’t think we’d like to have gays this year, thanks very much,’” he said before winning his fourth seat on council.

One accomplishment that he’s relieved to have finally checked off his list is finding a new home for Vancouver’s queer community centre, Qmunity, and securing $7 million from the city to help fund it. (Though he still hopes to also secure affordable housing for HIV-positive people in the units above Qmunity, once its future home at the northeast corner of Davie at Burrard Street is built.)

And Stevenson still gets a few goosebumps when he remembers his successful trip to Sochi, Russia as deputy mayor in February 2014.

It was the eve of the winter Olympics, and in the wake of a summer’s worth of anti-gay legislation and rhetoric from Russian president Vladimir Putin’s regime, Stevenson travelled to Sochi to lobby the International Olympic Committee to protect LGBT people from discrimination in would-be host cities.

He didn’t know how far he would get: responses to his outreach had been sparse and the IOC didn’t seem too receptive, but he was determined to try. On his second day in Sochi, he received a note inviting him to meet some IOC representatives at a hotel at 5pm. The impeccably dressed greeter was all smiles as Stevenson stepped into the lobby. Too smiley, as it turns out, as the greeter extended his hand to shake with the man he thought was the prince of Luxembourg. Undeterred, Stevenson met with the delegates and within about half an hour, he says, had received assurances that the IOC would amend its anti-discrimination charter to include protection for LGBT people.

Stevenson was taken aback. He was ready to do battle, he says, but here was victory.

“Nothing is impossible,” he says again, looking back on the lesson that he has consistently learned throughout his life.

“But you constantly have to compromise,” he adds, “because you’re one voice and there are other people who have voices just as strong, who have different opinions. So you have to make sure that you make your voice known.”

His worldview has been shaped by a strong faith, he says, rooted in part in the constancy of change. Everything is always in the process of changing, he explains; the only thing that is true is change. As people, we have to embrace that change, be a part of it, and ask ourselves how we can try to help shape it for the betterment of our community, and all of humankind.

And within those discussions and never-ending debates, it is essential to have LGBT people at the tables where decisions are made, he emphasizes.

“Allies don’t live our lives,” he explains. “It’s great to have allies — it’s better than having enemies,” he laughs. But nothing replaces lived experiences. “I think a caucus is far lesser” if it lacks a diversity of people and perspectives to help shape policy, he says.

Tim Stevenson’s rainbow-stencilled door at city hall. Credit: Courtesy Tim Stevenson

Perhaps his greatest legacy, he says, is that he’s been able to sit at the table as an openly gay man and have a voice.

Asked if his decision to step down for the next election is at all connected to what some journalists have called Vision’s implosion, as incumbents, including Mayor Gregor Robertson, step away and staff dwindles to none, Stevenson objects.

“Not at all,” he says. “And I don’t agree that Vision is imploding whatsoever.”

He admits that at times it’s been frustrating trying to accomplish goals such as eradicating homelessness with what he considers insufficient support from other levels of government. “It’s been very frustrating at times, and yet I think we’ve accomplished a huge amount,” he says.

He says he didn’t know about Robertson’s plan to not seek another term when he made his own decision to retire.

Now more than ever, he says, he hopes Vision Vancouver will seek out and nurture new LGBT candidates to run for office. It would be “a real loss” if those voices disappear, he says. “Our caucus would be diminished.”

As for Stevenson, he says he’ll continue to teach his western religions courses part-time at Langara College, and perhaps take an extended trip with his husband.

Tim Stevenson and his husband Gary Paterson were both awarded Queen’s medals in 2013. Credit: Nathaniel Christopher/Xtra

And what will he do once the dust settles? “I’m not one to sit around very much, but the one thing I do know from my experience in life is that nothing new begins to bubble up” until the previous step is relinquished, he says.

“I’m kind of excited: what will bubble up? Maybe I’ll become a monk,” he laughs.

“It’s been a thrilling, thrilling journey for me, in my life,” he says. “I’ve been so grateful to be gay and to have these opportunities and to meet people from all walks of life.”

He’s particularly grateful to have had the opportunity to be part of the gay liberation movement for the last four decades. To dedicate his life to something he believes in with his heart, soul and mind “is a rare opportunity to give life meaning and purpose,” he says.

“I have seen changes in the past 40 years I could never have imagined,” he says. “What a blessed life I’ve had.”

“It’s been joyous to be an openly gay person — to be who I am.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra