On that sweet and inevitable morning three centuries from now when the Roman Catholic Church apologizes for its sins against gay-kind, Oscar Wilde will be canonized as the patron saint of queers. It’s as simple and complicated as that.

The Pope, whoever she is in the 24th century, will kneel on her lesbian knees in the Sistine Chapel and call for St Oscar’s intercession. She will pray for the world to turn its attention to De Profundis, the long letter St Oscar wrote to his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, from jail, an epistle of romantic theology, haunting sorrow and decadent spirituality marking the author’s conversion to Catholicism.

Her prayer will be granted, and the world will read.

Fortunately you don’t have to wait: De Profundis is available today, as shocking and weird as it was when western civilization’s most famous homosexual wrote it in 1897. And if you can get yourself to Stratford, you can also hear William Hutt read from De Profundis, as adapted by Wilde’s grandson, Merlin Holland, on Tue, Aug 1 (which kicks off Stratford’s month long festival, A Wilde Celebration).

If you take the De Profundis plunge, get ready for a change in perspective on good old Oscar: The author here is not the smug smart-ass who gave us An Ideal Husband and The Importance Of Being Earnest.

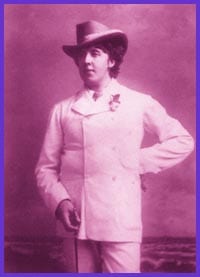

His legendary pink suit and green carnation have been replaced with a beggar-martyr’s rags, the prison uniform he was forced to wear after being locked away on sodomy charges. Gone too are the epigrams and Protestant faith he honed as a child and student in Dublin.

This Wilde is pure mystical Catholic, a born again queer Jesus freak, a divine lover in a dangerous time before Tammy Faye and the Log Cabin Republicans made it okay to be God-fearing and gay.

Wilde explains the source of his legendary eloquence in De Profundis: “Christ, like all fascinating personalities, had the power of not merely saying beautiful things himself, but of making other people say beautiful things.” And later: “Christ, through some divine instinct in him, seems to have always loved the sinner as being the nearest possible approach to the perfection of man… he regarded sin and suffering as being in themselves beautiful holy things and modes of perfection.”

Not that Wilde conceived of his homosexuality as a sin. Remember that mere months before his conversion to Catholicism, Wilde stood at his trial to utter the first public defence of gay love in British history; surely this is the first of his miracles. He praised the love of the Biblical figures of David and Jonathan: “The love that dare not speak its name is the most beautiful, fine, and noble form of affection.”

Wilde’s writings before De Profundis are full of virtuous, homoerotic heroes, from the queer soldier who weeps at his lover’s execution in the play Salomé (the story of John the Baptist and his freaky girlfriend) to the beautiful nobleman in The Happy Prince who gives his gold and jewels, then his eyes and flesh, to feed a starving young playwright.

Wilde particularly identified with Mary Magdalen, the disciple who was also a prostitute. He imagines himself in De Profundis as Mary weeping over the erotic form of the murdered messiah, his “body swathed in Egyptian lien with costly spices and perfumes.” Christ is at once lover and saviour.

Wilde linked his image of “Christ the divine lover” to the image of St Sebastian, the hunky boy-saint who was martyred by arrows after refusing to renounce his religion to the Roman army in the 4th century. Sebastian was made an icon of homoerotic art by another well-known queer artist in the Renaissance, known to generations of popes (and non-popes) as Michelangelo.

Sebastian was the name Wilde took to protect his identity after his release from jail. He used this holy name until his death in Paris in 1900. St Oscar received the final sacraments on his death bed, and died a Roman Catholic in good standing.

We’re not used to thinking of Wilde as a monk and mystic, and yet that is what he chose to be at the end of his life. He wrote that “Roman Catholicism is the greatest and most romantic” of world religions, “all of which are colleges on the campus of one great university.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra