"Kids are beginning to express their sexuality at this point. Their hormones are kicking in," says Natasha Garda of her middle school students.

While the fight for gay-straight alliances (GSAs) and more equitable learning environments in Ontario high schools raged over the past several years, some public-school elementary teachers have been quietly advancing their own equality agenda, sometimes as early as the primary grades.

Teachers say elementary and primary school children are at an age where they are more open-minded and often haven’t had time to build prejudice.

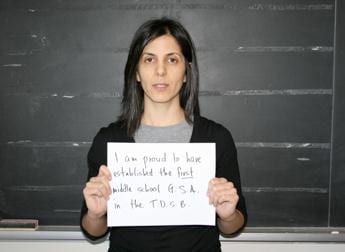

Toronto’s Westwood Middle School has had an elementary-level GSA since 2010. And the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario (EFTO) – the union for public-system teachers – sees itself as a champion of social justice, boasting an entire department dedicated to getting queer-inclusive and anti-oppressive education into classrooms as early as the primary level.

This is despite the fact the provincial government backed away from adding discussion of homosexuality, cyberbullying and sex work to the curriculum when it abandoned proposed changes to sexual education and health. Many teachers are simply finding ways to work it in.

“We’ve designed a lot of materials for teachers as a way of following the curriculum but also teaching about acceptance,” says Susan Swackhammer, ETFO’s first vice-president. Swackhammer’s University Avenue office in Toronto contains a kit full of social justice stories for kindergarten to Grade 8, covering topics such as HIV/AIDS. Each story is directly labelled with a corresponding part of the existing curriculum, such as a drama or comprehension.

“It all has to come from the curriculum, and this way we can still meet the ministry expectation,” she says. “The curriculum has always been based on a heterosexual world.”

That would have changed somewhat with the failed health and sex education curriculum, shot down in 2010 after the provincial Conservatives insisted it would teach primary students how to give blowjobs, and other ostensible exaggerations. The document Ontario teachers are working from now was written in 1998, a time when every child didn’t have the sexuality-packed internet literally in the palms of their hands.

“You need to be talking to kids about what’s really going on,” Swackhammer says, noting children are much more accepting of differences than many of their parents. “Primary kids love you despite your warts . . . Unfortunately, they have parents. We have to deal with adults’ level of understanding on these issues. But if you leave these kids alone, they get it.”

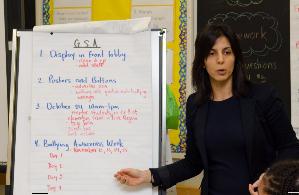

It’s for that reason that Westwood teacher Natasha Garda laid the groundwork for her school’s GSA, despite there being no elementary-school precedent. Westwood educates students from grades six through eight, an age where many know they’re queer but few are ready to say so.

“I’ve had a lot of kids come out to me privately,” she says. “Kids are beginning to express their sexuality at this point. Their hormones are kicking in.”

The club is designed as a safe space and promotes an agenda of acceptance in the school. There are about 15 members, give or take, who lead activities designed to make students think about gender roles, equality and how much it can hurt when people use the word “gay” as an insult.

“I don’t think it’s something people should be saying,” says Nicole Bates, one of the Grade 8 students in the GSA. “What is gay? It’s not anything bad at all.”

Even in the time their GSA has been active, Bates says, she hears people saying it less often.“I think people won’t be saying, “Oh, that’s so gay’ in high school. Because if you say that, you’re not mature.”

So far, the Westwood GSA has no members who are “out,” but that’s pretty typical for the age group, says Garda, a former board chair at Toronto’s 519 Community Centre. It has, however, created a safe space for all kinds of people who feel marginalized, and it has managed to attract many of the school’s “cool kids.” Kristiana Valcheva, in Grade 8, says she joined the GSA because she was having a hard time fitting in and wanted to go somewhere she wouldn’t be judged.

“We all judge,” she says, seeming confident and introspective. “Sometimes we don’t even know we’re doing it. The GSA is a little start at becoming better.”

Normalizing the idea of joining a GSA at this age paves the way for high school, when students are more likely to want to have relationships and might need more support, says Grade 8 student Mela Tabaku. “If they joined a GSA in middle school, they will be more comfortable about joining in high school.”

The Westwood club has faced some opposition from parents who think middle school is too young, but Garda has received enough accolades and support to let the negative stuff slide. In November, she received the Canadian Safe Schools Network award of excellence for her pioneering efforts, which are now being copied by other schools across Ontario.

She’s also had the strong backing of her school’s principal, Helen Fisher, who believes that creating supports for all students is a requirement, not an option.

“I think it’s the role of every school, even an elementary school, to be a safe and inclusive environment for everybody. Quite often when you go into a school, that’s not the case. Especially at a middle school, they tend to lash out at other kids, not really knowing who they are themselves.

“Even Grade 6 is too late,” she adds. “I’d like to start as early as kindergarten.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra