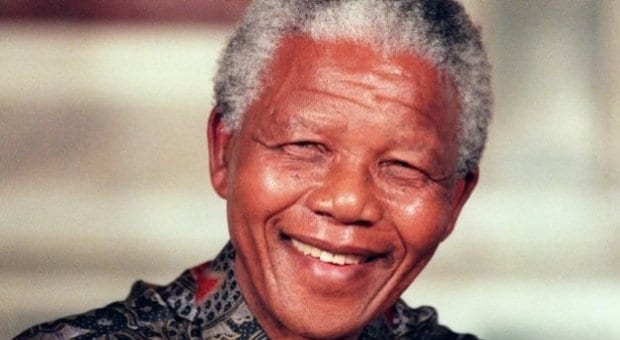

“Our nation has lost its greatest son,” South African President Jacob Zuma said Dec 5, as he announced the death of Nelson Mandela, who devoted his life to fighting the oppression of apartheid and who in 1994 was elected South Africa’s first black president. Mandela, who was 95, died at his Johannesburg home.

Zuma spoke for many around the world when he said, “Although we knew this day would come, nothing can diminish our sense of a profound and enduring loss.”

For his strident opposition to South Africa’s violent segregationist policies, Mandela endured a 27-year imprisonment, including several years at Robben Island, becoming an international symbol for those involved in fights for freedom and equality around the world.

“During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to the struggle of the African people,” he said during his trial in 1963, alongside other ANC leaders.

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But, if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

After years of refusing to negotiate with the apartheid government, Mandela decided to renounce that approach, seen as a radical move. According to Time magazine editor Richard Stengel, Mandela was deemed in some quarters to be a traitor who had sold out the anti-apartheid movement, but the move eventually led to South Africa’s first democratic election.

Mandela, known affectionately by his clan name, Madiba, was also revered for his ability to seek national unity and reconciliation even after his long incarceration, establishing a Truth and Reconciliation Commission that heard the stories of those oppressed under apartheid while extending a hand to those who were persecutors.

Mandela and former South African president F W de Klerk, who ordered the former’s release in 1990, were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993.

Mandela’s decision to step away from the presidency in 1999 also earned him praise, a move seen as a marked departure from the pervasive political instinct to hold on to power.

In his tribute, former US president George H Bush spoke of Mandela’s “remarkable capacity” for forgiveness, saying that it provided the world a “powerful example of redemption and grace.”

Reacting to his passing, American President Barack Obama said Mandela “belongs to the ages,” adding that he “achieved more than can be expected from any one man.”

In 1996, Mandela signed off on a new South African constitution that explicitly prohibits discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. In 2006, the country legalized gay marriage.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) notes that Mandela encouraged his fellow South Africans to discuss HIV/AIDS openly, to “make it appear like a normal illness.”

In February 2010, Edwin Cameron, who is gay and reportedly the first senior South African public official to disclose his HIV diagnosis, reminisced about his appointment to the high court by Mandela at the end of the freedom fighter’s first term as president in 1994.

“I can truly say my sexual orientation was irrelevant. I think a lot of other things – political, legal and personal – played a role, but that didn’t count against me. That’s a remarkable achievement,” Cameron, who is currently a justice on the country’s Constitutional Court, told The Guardian on the 20th anniversary of Mandela’s release from captivity.

Still, Cameron says, there is “widespread ignorance and homophobia” toward gays and lesbians.

“Lesbians, and LGBTI people who do not conform to culturally approved models of femininity and masculinity, live in fear of being assaulted, raped and murdered by men,” Amnesty International’s report, entitled “Making Love a Crime: Criminalization of Same-Sex Conduct in Sub-Saharan Africa,” states.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra