Credit: Courtesy of John Kozachenko

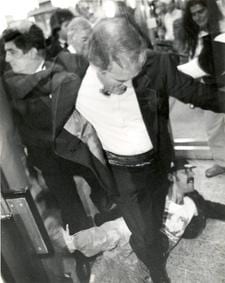

AIDS activist John Kozachenko (on the ground) tangles with former BC premier Bill Vander Zalm over Bill 34, which called for quarantining persons with AIDS. Credit: Courtesy of John Kozachenko

Pacific AIDS Resource Centre keeps AIDS awareness front and centre at Pride. Credit: Courtesy of John Kozachenko

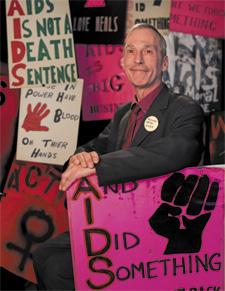

John Kozachenko. Credit: James Loewen

“Standing up was not a choice,” John Kozachenko asserts.

“It was about survival. Survival at its basic. That’s the only choice you have. It’s either this or death.”

Twenty-five years after the Vancouver Persons with AIDS Coalition was founded, Kozachenko is the lone survivor of its 15 original members.

He was diagnosed with an AIDS–related complex in a University of Toronto epidemiology study at the Toronto General Hospital in 1984, over a year before HIV antibody blood tests were available in Canada.

“When the blood test became available,” he says, “it backed up their original diagnosis.”

Shortly after arriving in Vancouver, Kozachenko got involved with the coalition, which started out as a group of people who met for coffee in the St Paul’s Hospital cafeteria.

“One night a week we’d get together and talk about issues with our health. There was no treatment at that time,” he recalls.

Members wasted little time going public with their concerns.

In 1986 about a dozen of them staged the first-ever AIDS demonstration in Canadian history at the Parliament Buildings in Victoria. They called on the right-of-centre Social Credit government to establish a viral testing lab in Vancouver.

“There was not much public support; it was just ourselves and our friends at that time,” Kozachenko says. “Public activism was limited to the people who had it themselves.”

He points to a handmade pin on his suspender, which reads “Person with AIDS.”

“They gave us these pins. This is an original pin from the 1986 protest,” he says.

“We took the ferry over, and people were grabbing their children, making sure kids weren’t around us.”

Even among his friends, he adds, there was still misinformation about the disease.

“It was quite difficult to deal with,” he remembers.

“I was a political activist at the time; I had anarchist friends who were asking me questions like, if they could contract it if I shared a cup of coffee with them.”

That lack of understanding, he says, was reflected in public policy of the day.

In 1987 the provincial government introduced Bill 34, legislation that called for quarantining anyone who was “likely to willfully or carelessly or because of mental incompetence, expose others to the disease or the agent.”

The idea that people could be banished into isolation was galling to PWA members, who saw the bill as a violation of their civil liberties.

They rallied — 200-strong — at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

And again, they took the fight to BC’s Legislative Assembly.

“We got a helicopter to go over to Victoria,” Kozachenko recalls. “I ripped a copy of the bill, threw it over the heads of the Social Credit members and yelled, ‘Education works and Bill 34 won’t!’”

PWA founding chair Kevin Brown expressed the community’s collective outrage in an open letter to the Legislative Assembly that ran in the January 1988 edition of the coalition’s newsletter.

“If you scoff at our alarm of possible abuse of this legislation,” he wrote, “or think us foolish to fear senseless quarantine in BC then take a moment to question the survivors of the Nazi concentration camps, or better yet and closer to home, ask Japanese-Canadians if in their wildest dreams they could have conceived of the bleak holding camps in the Rockies during the 1940s, then maybe our fears are not so groundless after all.”

Yet another early battle involved access to the then-experimental drug AZT, which was the only drug available for treatment of infections caused by HIV.

“AZT has become the drug with that history that it poisoned so many people,” says Kozachenko. “I think that people were forced to do it, yet they were getting anemic because of it.”

AZT was approved for use in Canada in 1987. British Columbians living with AIDS were required to shoulder 20 percent of the cost, which often totalled in the thousands of dollars per year.

“I had a friend who was collecting the bills and he joked about pasting them up and wallpapering my bathroom,” Kozachenko says.

Stigma and fear forced many people to pay up, he adds.

“You don’t want to be known as an HIV-positive person, so they paid for the drugs.”

In 1990 Kozachenko helped establish the Vancouver chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), an international direct-action advocacy group committed to ending the AIDS crisis. The Vancouver chapter, which lasted about two years, was formed to fight Bill 34.

Groups like AIDS Vancouver and BCPWA, which received government grants, “could not focus on that [kind of activism],” says Kozachenko, so they left it up to ACT UP.

“They said to government, ‘You can deal with us or you can deal with ACT UP.’”

At a 1990 Social Credit Party fundraiser at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre, ACT UP staged a “die-in.”

“Your friends are doing chalk marks around your body, showing that people died there,” explains Kozachenko, who ended up being arrested with four others for the stunt.

The protest brought people living with HIV into direct confrontation with then-premier Bill Vander Zalm.

“[Bill Vander Zalm and his wife, Lillian] stepped over me and I put my legs together, and Lillian was on his arm and she tripped over me. She screamed when she was going down,” Kozachenko recalls.

The following year, Kozachenko and about 20 other ACT UP members again confronted the premier, this time outside a television studio.

“We met earlier at McDonald’s and got some ketchup that we smeared on their limousine, and the media was there.

“They reported, ‘Oh, there was this red substance, allegedly infective, possibly spit.’

“I was accused of spitting at Vander Zalm, but I would never do that.”

Kozachenko was charged and acquitted of mischief as a result of a dent, scratches and scuff marks found on the car’s hood.

At his trial he told the judge the ketchup symbolized “the blood of the people with AIDS on the hands of the provincial government.”

“We lost a generation. People that are gone that really shouldn’t be,” says Ken Buchanan, current vice-chair of BCPWA, now renamed Positive Living BC.

“Nowadays we’re so lucky that very few people are dying of AIDS; we tend to be living with HIV.”

Buchanan sees the BCPWA’s upcoming 25th anniversary gala as an opportunity to recognize what people living with HIV have weathered.

“We are acknowledging those who have passed with huge respect and those that survived — the long-term survivors,” he says.

“Those that lived are the minority. They are out there. We’re so grateful they are here and they can tell their stories.”

He points out that newly diagnosed individuals can look forward to a much brighter future than those diagnosed in the early years, thanks to advances in HIV treatment.

“Young people today getting HIV — almost everyone getting HIV — are going to die of something else,” Buchanan notes.

“We are seeing our members pass away of natural causes, and all the HIV doctors are telling us now to treat the HIV and look after your health.

“We’re incredibly fortunate in BC that we have access to the medicine; every citizen of BC gets free HIV meds.”

One of the biggest issues today is treating people who don’t know they’re positive, Buchanan adds. He refers to the 2010 ManCount report, which revealed that one in 40 gay men in Vancouver are HIV-positive but don’t know it.

“They get sick, are diagnosed, and it’s too late — or almost too late.

“People getting tested regularly know their status, can deal with it and maintain a good quality of life.”

Kozachenko attributes his own longevity to healthy living.

“I’m totally out of the closet and am happy with my life the way it is,” he says. “My meds are working fine and I finally found a good regimen of drugs I can use with just mild side effects, but I don’t mind it.”

He believes the early activism of people living with AIDS has left a lasting impact.

“I think we were very effective,” Kozachenko says. “I still have people coming up to me thanking me for the activism taken.

“I did it for them, but I did it for myself, too. It needed to be done.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra