Government officials say Canada’s looming effort to purge criminal convictions for consensual homosexual acts could cost $4.1 million and face “nightmarish” bureaucratic hurdles, Daily Xtra has learned.

Nevertheless, public servants told the government they would have been able to start the process by September 2016, according to documents released under access-to-information laws, raising questions as to why the review still hasn’t started.

On Feb 27, 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced he would seek a posthumous pardon for Everett Klippert, who was labelled a dangerous offender for consensual gay sex. The next day, his spokesman said the government will review all convictions of “buggery” and “gross indecency” laws prior to 1969, when they were restricted to mostly non-consensual activity. The government has only said publicly and to bureaucrats to look into cases before 1969, but there’s no mention of afterwards.

In 400 pages of exchanges obtained by Daily Xtra, Parole Board of Canada employees say roughly 6,000 sentences could be reviewed, with an RCMP search showing the oldest dating back to October 1939. “A manual review of each file would be needed to determine the circumstances surrounding the convictions,” according to one memorandum.

However, the Parole Board said in the documents that it would be ready, “to post information on its website for September 1, 2016 to inform individuals with the specific convictions that they may apply for clemency.”

The documents suggest the Liberals are interested in modelling an Australian program that involves cost-free reviews of convictions for people who feel they were charged because of homophobia, but bars them from any compensation.

The documents also reveal that over 300 Canadians convicted under either charge have requested pardons on their own since 2000, with a success rate of 98 percent.

The government did not respond to Daily Xtra’s request for comment on the documents, which date from February to July 2016. The lack of a timeline and plan of action has frustrated activists.

Australian model, with no compensation

According to the documents, Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale was leaning toward replicating how the Australian state of Victoria is expunging records. A June 6 email says Goodale’s office wants bureaucrats to study how the model “can be applied in the Canadian context. As they point out, there is no need to reinvent the wheel.”

Since, Sept 1, 2015, LGBT Australians in Victoria (or their relatives, if they are deceased) have been able to request a cost-free review of any convictions they feel were motivated by homophobia. Investigators are asked to consider any criminal convictions that requesters feel were motivated by homophobia; they are not restricted to a list of criminal charges associated with homophobia. For example, this allows a review of convictions under vague laws about public sex that were used to arrest men in private bathhouses.

The minister’s office then parses through any available evidence and decides to expunge the records if “on the balance of probabilities” the person would likely not have been charged under present-day laws. The agencies only act on “written evidence” from either court records or from the other person involved in the act, if they are alive.

The Australian state’s program has no end date, operates under strict confidentiality and offers an appeal at the state’s civil court, as well as another application if more information becomes available. However, the law states, “a person who has an expunged conviction is not entitled to compensation of any kind,” regardless of whether they served jail time or had to pay fines.

Constitutional lawyer Douglas Elliott, who helped Egale Canada publish an extensive review in June on how the government could issue pardons and apologies to persecuted queer Canadians, says the Liberals have a constitutional obligation to offer compensation.

“When your charter rights are violated, you’re entitled to damages from the state. This isn’t rocket science — this isn’t some special favour that they’re doing,” he says. “They certainly spared no expense in persecuting people.”

Gary Kinsman, who has researched the persecution of LGBT Canadians for decades, notes that in 1992, the Canadian military compensated former soldier Michelle Douglas and other ousted soldiers in a settlement after she sued for employment discrimination.

“The judicial process recognized that real injustice had been done to these people, and it involved some form of compensation,” Kinsman says.

It is not clear whether the government still favours the Victoria model, and whether it intends to compensate Canadians if their convictions are expunged.

Four options

Prior to Canada’s public safety minister weighing in, bureaucrats had proposed four options to fulfill the federal government’s promise — each with their own shortfalls.

The first option would have applicants ask Parole Board officials to investigate their case. The bureaucrats would probe all existing records, and make a recommendation to the minister of public safety on whether to issue a “free pardon,” which would result in a letter to all relevant agencies notifying them to erase the wrongful convictions.

This would have started with a publicity campaign aimed to start Oct 1, and would fall under the Royal Prerogative of Mercy, an exceptional process meant to void individual, unjust convictions that have demonstrably caused harm — compared with the regular pardon system that rewards well-behaving people after they were legitimately convicted.

The second option would have applicants pay a $631 fee to request a “record suspension,” formerly known as a pardon, which is a review of their entire criminal record, and not specific convictions. If deemed successful by Parole Board employees, their history of convictions is kept separate in criminal record checks, but put back in if they commit a crime. The waiting period for these requests is five to 10 years.

The third option involves a similar process, with the cost and waiting time waived and a review of just the relevant convictions. This would require a legal amendment to be passed in Parliament, which could be tabled in spring 2017 alongside some unrelated amendments to the pardon system that the government has mulled.

The fourth option, expungement, echoes the first option. Applicants would ask to have their criminal records deleted, but this would be through a new process requiring Parliament to pass an amendment. This process would have bureaucrats make the decision, instead of a government minister.

Bureaucrats also briefly explored more efficient options

One option involved searching for available records and notifying people who were convicted — as well as the families of those who are deceased — that they could have their convictions removed. But Parole Board employees dismissed the idea over privacy concerns, with one noting the department “must be careful not to ‘out’ any individual who does not want to be named or implicated. Self-identification may be the safest way to go about it.”

Another idea proposed wiping all records from the federal police database in one action, including involving pedophilia or rape, but advised against this as it would undermine public trust in the legal system and would not erase older paper records.

A third idea would have the government issue an apology and a statute — an official notice posted to the federal database and all record-keeping agencies, that most convictions under both charges are likely not valid — “without the benefit of removal from the record.”

Delays and precedents

As of early June, the Parole Board had a backlog of over 4,000 pardon applications, with most filed more than four years ago. Bureaucrats worry that in reviewing LGBT convictions, “there could be significant costs and/or delays and increases to the current backlog.”

The documents include cost estimates for launching a toll-free number and mail room, hiring investigators and reviewers — with a total annual cost ranging from $2.3 to $4.1 million. These costs do not include compensation.

Justice Department officials also warn that such a review could prompt a demand for similar programs for old marijuana and prostitution laws.

“We can expect a demand for similar treatment for past convictions under other laws that were subsequently repealed,” reads one Parole Board briefing. “A federal posthumous grant has never been issued and will be precedent-setting; potentially increasing the volume and type of future applicants,” advises another.

Nevertheless, the Parole Board said that, “the application process, eligibility criteria and specialized application forms could be developed over summer 2016,” with a rollout early this fall. However, on Oct 10, Trudeau’s spokesman told the Toronto Star the government still hadn’t chosen a timeline for this process.

In a sit-down interview with Xtra in June, Trudeau said he was committed to making amends with thousands of LGBT people who were mistreated by the state, but said it was still too early to tell how those amends would come to fruition. “We do need to recognize the terrible mistakes made in the past that we need to make sure we learn from, that we reflect on and that we make amends for,” he said. “And however that comes and whatever form that takes will be something that we’ll have to reflect on, and discuss on and exchange on.”

On June 22, 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told Xtra he would make amends with LGBT people prosecuted by the Canadian state. The government was support to start the process of clearing convictions of buggery and gross indecency in September 2016.

PTP Video

Repealing anal-sex charge

On April 8, 2016, Trudeau’s spokesman Cameron Ahmad told Daily Xtra the Liberals will study repealing Criminal Code section 159 — which forbids anal sex “in a public place or if more than two persons take part or are present” and puts the age of consent for anal sex two years higher than the general consent age of 16.

The documents reveal that bureaucrats expected they’d be asked to include such convictions in the review, anticipating a summertime announcement that still has not come. “Plans are underway to announce in June 2016 the tabling of a bill to repeal section 159 of the Criminal Code, which creates the offence of anal intercourse,” reads one memo.

Bureaucrats also noted that no prisoners currently serving sentences under a section 159 conviction would be eligible for a pardon. “A review had revealed that none of the 27 cases involved consensual sexual activity between adults,” reads one email. However, those convicted decades ago might be eligible.

That contrasts dramatically from the two charges the government has pledged to review. The documents show that since 2000, 20 people applied for a pardon involving “buggery,” of which 17 were issued, all before pardon rules were tightened in 2012.

For “gross indecency,” 293 of 296 pardon requests were granted, with 13 issued after 2012.

Costly, difficult to access old records

The documents anticipate a lengthy, costly process to access decades-old documentation, but notes that that “without being able to access historical records, there is a risk of granting clemency . . . to unmeritorious individuals.”

While Canada has a national, electronic database of criminal records, the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) only dates back to 1972.

Bureaucrats note that some jurisdictions throw out decades-old records. “Furthermore, dated material may often only be in hard copy or microfiche, and may require making request to the courts to access and search archived materials.” If no records can be found, a sworn statement could be made, but certifying such affidavits costs money.

While the federal government updates the Criminal Code, city and regional police often arrest people under these federal laws, which are then tried by provincial-court judges. That means conviction records are held across the country. But the federal government can’t compel other jurisdictions to complete searches or to delete their records.

“If the record exists in local municipal or provincial/territorial police records, there would be no obligation to adhere to federal legislation and erase the convictions and associated records,” said one bureaucrat.

Another wrote: “If [the] effect of pardon is to seal the record: notifications may be nightmarish and time consuming and there may be cooperation with provincial authorities issues (court/police forces etc. may be reluctant to be flooded with these requests).”

Kinsman says he hopes the government doesn’t back down on its promise in the face of these obstacles.

“It’s a very complicated situation, but a complicated situation should not be used as an excuse for not bringing about what brings about greater justice for people.”

Activists want more, soon

The Liberals have only publicly endorsed a review of convictions involving buggery and gross indecency until the government curtailed both sentences in 1969. They are also looking at repealing the anal-sex law. But activists want a deeper review.

Kinsman says the government should allow persecuted gender and sexual minorities to have authorities review their convictions under all laws, from all time periods — not just when the laws were curtailed in 1969. In the Parole Board documents, officials note that after 1969, buggery and gross indecency convictions persisted, with “over 200 a year until 1988,” when they were removed from the Criminal Code.

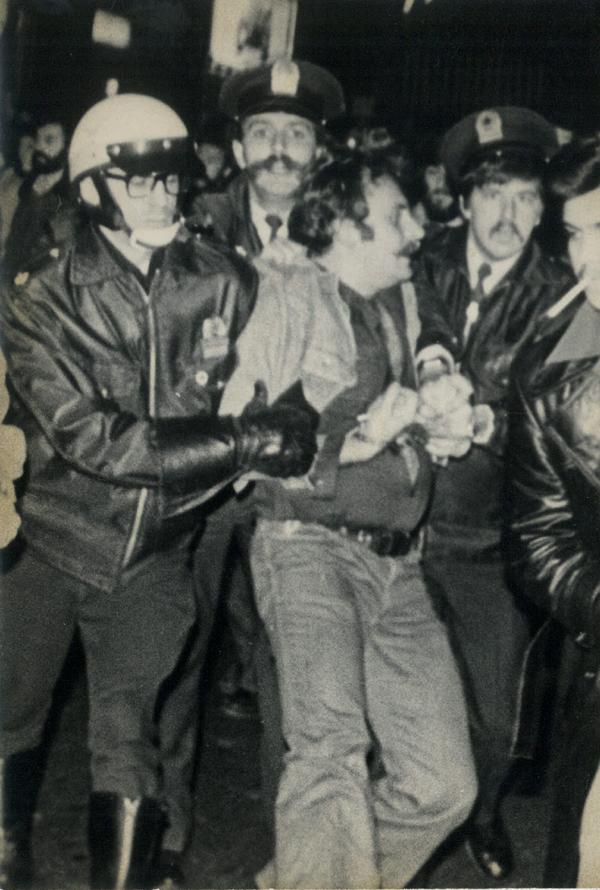

Kinsman also believes police charged even more queer people after 1969, because officers still enforced vaguely worded laws. For example, the 1981 bathhouse raids saw hundreds of gay men charged under “bawdy-house” laws.

“To not look at what happened after 1969 is a serious problem, given what we know about all the police activity that took place,” says Kinsman, who is part of the We Demand an Apology Network.

Both the Network and Egale want the government’s review to consider people who were charged with an offence but not convicted, because some people lost their jobs and marriages after being publicly accused of homosexuality.

They also want redress for Canadians kicked out of the public service and the military for suspected homosexuality. On Oct 31, Elliott filed one of two class-action lawsuits seeking $600 million in damages.

Both groups say they haven’t been consulted by the government, and fear the Liberals will put forward a policy unilaterally without checking with activists about shortfalls.

Elliott claims that the Prime Minister’s Office told him repeatedly this summer that the review would be coming within weeks.

“We’re getting a bit tired of that story. It’s sad, frankly, because I truly believe that there isn’t political resistance,” Elliott says, noting that Germany and Britain have pushed ahead with similar initiatives. “We’re playing catch-up with other countries.”

“It’s very frustrating, especially when I know that the people who are most affected by this are the pioneers of our community, the people who have experienced the worst years of discrimination — and they’re not getting any younger,” he continues.

“And I don’t want the prime minister apologizing to a cemetery,” Elliott said.

“I expected better from this government.”

Legacy: January 1, 1970 12:00 am

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra