Credit: Neal Freeland.

Facebook pulled this poster down after it was shared by AIDS Action Now. Credit: Ryan Conrad

Tim McCaskell co-founded AIDS Action Now 25 years ago. Credit: Ryan Conrad

Poster/virus is back, and it has mutated.

The project – first produced by activist collective AIDS Action Now (AAN) in 2011 – saw Toronto, and the web, plastered in a series of posters that tackled, among many issues, the question of HIV-nondisclosure criminalization in Canada.

In October, the Supreme Court ruled on new procedural guidelines around disclosure that have widely dissatisfied many HIV/AIDS activists. Since then, AAN has been decorating the streets again, this time working with a new set of artists and community collaborators and tackling not just disclosure, but a host of concerns, such as prisons, sex work, stigma, poverty, queer women and aboriginal issues. The posters will be launched officially at the Art Gallery of Ontario on Nov 28; the day after AAN will host a discussion and documentary on the history of AIDS activism.

“Last year, the posters provoked so many interesting discussions that we couldn’t even keep up with them,” explains Jessica Whitbread, one of the campaign’s curators.

“We want the posters to create a conversation,“ adds Alex McClelland, also a curator. “With this whole project, the idea is we are a little bit fed up with who controls the AIDS discourse.”

To that end, the posters are indeed provocative. One particularly confrontational work, by Ryan Conrad, shows a high-contrast image of the Supreme Court dotted by images of men having sex, with the text “Fuck the Supreme Court” modified by a footnote: “Condoms and low viral load required by law.”

Another Conrad poster takes up male prostitution, showing a closeup of a rim-job and naming exposure, disclosure, stigma and criminalization as “working conditions.” It was this poster that – after it was shared on social networking sites – got the project’s page completely removed by Facebook under the auspices of “promoting community standards.” As a response, other users started posting the image in solidarity.

In Jess MacCormack’s poster, policing disclosure is broadened to include any act of telling. Her text reads, “Hey girl, I’ll tell you when I’m ready.” Heavy in digital and pop-culture imagery, MacCormack’s work interrogates new modes of expression and self-representation.

“I’m playing on the complexity of telling who we are and criminalizing that,” she explains. “The way people hook up now is navigated and mediated by the internet. The way we disclose and exchange in those places is totally different.”

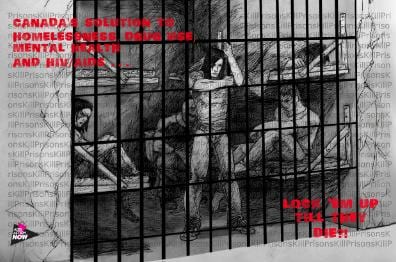

Even beyond disclosure, the law casts its shadow on much of the messaging in this year’s campaign. In the case of artists Neal Freeland and Giselle Dias, the criminal justice system literally hindered the creation of their poster, as Freeland was incarcerated as their collaboration began. Working over the phone until Freeland was released, the two constructed an image of an overcrowded jail cell accompanied by the message “Canada’s solution to homelessness, drug use, mental health, HIV/AIDS . . . Lock ’em up til they die?!”

“The mentality of the government is that if you put them in prisons, it’s somebody else’s problem and we don’t have to look at them,” Freeland explains.

Freeland, who is of Saulteaux descent, explores HIV and mass incarceration as they relate to aboriginal Canadians. In their artist statement, to be released with others in a poster/Virus zine, Freeland and Dias write, “In the Prairie provinces over 80 percent of the prison population is Indigenous and we see this as a form of on-going colonization practices (reserves, residential schools, 1960s scoop, foster care and now prisons).”

But perhaps the most interesting, if subtle, piece is from Micah Lexier, in collaboration with AAN veterans Darien Taylor and Eric Mykhalovskiy. Eight iterations of the AIDS Action Now logo address various barriers.

Although Lexier says it wasn’t his intent, the logos seem to house a subtle critique of AIDS activism and the organization itself – that action around these issues carries its own set of privileges.

“Being an activist is a luxury; we have the luxury to volunteer and do this stuff,” McClelland admits. “Not everyone does, and we’re conscious of that.”

However, Lexier’s poster also more obviously parses out some of the nuances that continue to complicate healthcare for people with HIV, even after the introduction of antiretroviral drugs. This, too, is a self-examining perspective, as the issue of access to treatment was a crucial cause for AIDS activists at the beginning of the epidemic.

In fact, AIDS Action Now began 25 years ago in 1987, organizing to demand standards of care in hospitals and access to new drugs. After the AIDS crisis gave rise to the conflicting approaches of New York groups such as Gay Men’s Health Crisis and ACT UP, activists Michael Lynch and Tim McCaskell founded a group that would focus entirely on advocacy, information and agitation.

“It was a civil war in the States. They spent so much energy attacking each other and undermining each other,” McCaskell remembers. “We had the advantage of having seen that, and we recognize that there’s stuff that we can do that service organizations can’t, and stuff service organizations can do that we can’t.”

“What was happening at that time was that there were a lot of organizations around AIDS prevention. People living with HIV didn’t have much presence there,” explains Darien Taylor, a woman who joined AAN shortly after its genesis. “AIDS Action Now was dealing with treatment, and that was really different.”

Indeed, the story of AAN has been truly remarkable in terms of the group’s coexistence with service and public health organizations. In fact, various organizations, such as CATIE, PASAN and the HIV/AIDS Legal Clinic of Ontario, emerged out of AAN’s membership but remain separate. This unique, if sometimes tense, relationship with the complex of AIDS organizations can be explained partially by AAN’s financial and organizational autonomy.

“Right from the beginning we said AIDS Action Now is a volunteer organization, and we will not receive money from the government or pharmaceutical industry,” McCaskell says.

“Other organizations have to be very careful about the advocacy work that they do, because they could very easily lose their funding,” Taylor adds.

Although the group experienced a lull after many victories, McCaskell points to a raucous confrontation with the minister of health, organized by McClelland, at the 2008 International AIDS Conference, as the catalyst for revival. With the appearance of issues like nondisclosure and mandatory minimum sentencing for drug users, Canadian AIDS activism had rediscovered its urgency and is now back in full throttle.

“In my experience, community volunteer organizations usually have the lifespan of about a decade,” McCaskell says. “For AIDS Action Now to still be going 25 years later, considering that we don’t have a staff, don’t have an office, that it’s nothing but volunteer energy, is really kind of extraordinary.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra