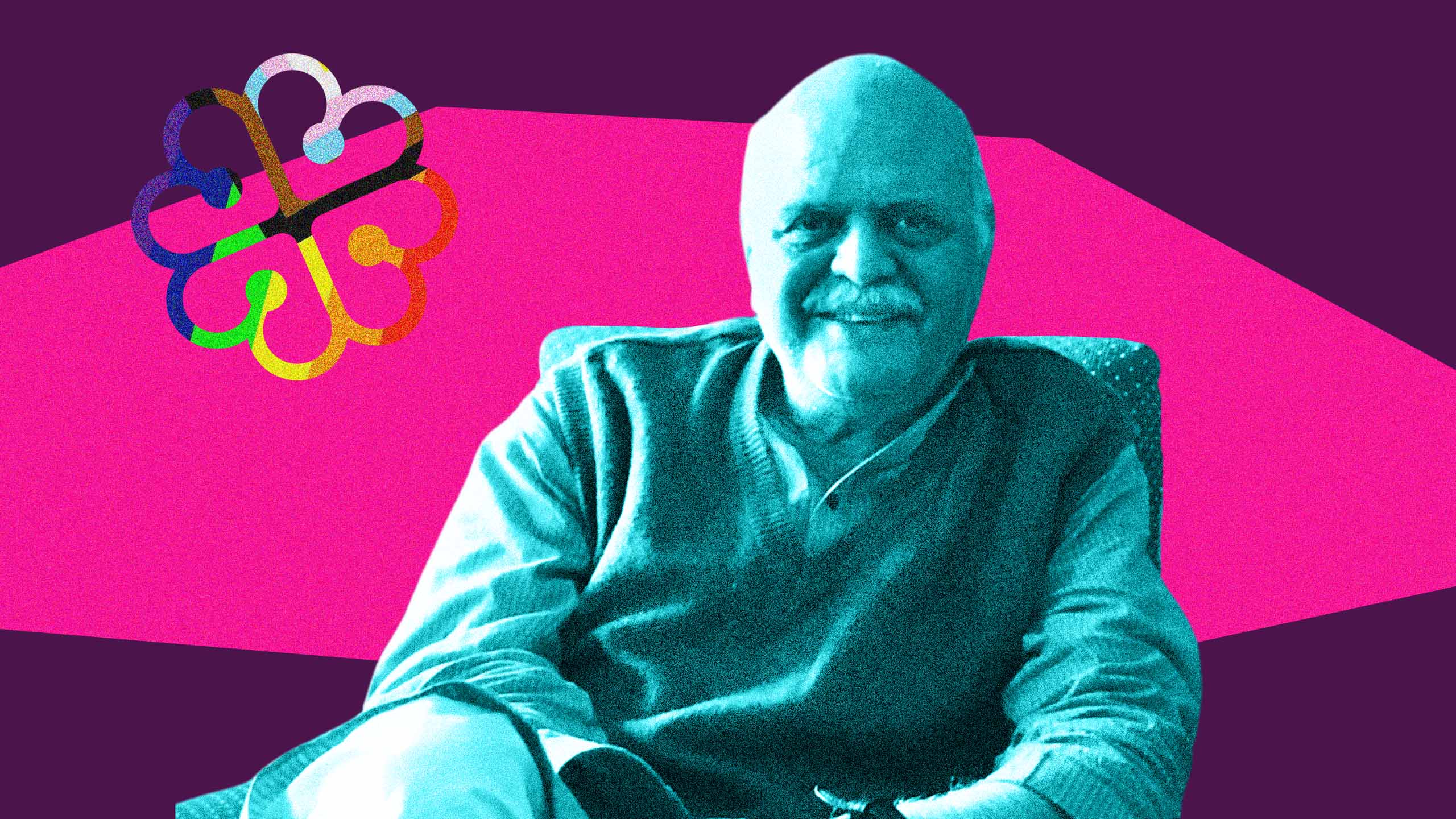

In 1976, Saleem Kidwai, a history professor at Delhi University, took leave from teaching to pursue a PhD at McGill University’s Institute of Islamic Studies. He wanted to live an openly gay life and heard it was possible in North America. His experiences in Canada would shape his life’s work of documenting South Asian queer history.

Kidwai was one of many South Asian queer people with a Montreal connection that the Falooda Collective uncovered in their research. Founded in 2021 with six members, the grassroots, institutionally unaffiliated Montreal South Asian queer history project aims to document queer South Asian presence in the city. “What makes us want to do this work [is] the erasure of South Asian queer [history],” Titas Banerjee, a collective member, tells Xtra. “One of the things I really want to do is to bring to light some of those stories, so they are heard and not just forgotten. For our generation and younger people growing up, it has an impact [knowing] that there have been people here for decades.”

Falooda’s first project was a memorial documentary on Kidwai, who passed away in 2021. Collective members pieced together his life story by interviewing people who knew him during his time in Montreal. Sunil Gupta, a photographer featured in the film, was one of the first people Kidwai befriended in Montreal. The two would often walk around downtown Montreal with their friend Fakroun, wearing queer-coded clothing as their own little act of what Gupta called “gay liberation.” Kidwai was wary of them at first, because he felt that looked a little too stereotypically gay for him. “So in public places, he kind of preferred keeping a few feet of distance from them, so he’s not presumed to be with these gay folks,” explains Falooda collective member Noon Ghunna. Those friends would nevertheless encourage Kidwai to explore his queerness, go to parties and make connections in the community.

It was during one of those parties that Kidwai’s stay in Montreal turned into a nightmare. On Oct. 22, 1977, when he was at Truxx Bar, a gay bar downtown, armed police barged in. They violently arrested him alongside 145 others, and threw him into a packed van. Kidwai was charged with “being in a bawdy house”—a place where indecent acts are deemed to have occurred—and forced to undergo STI testing, according to the collective.

Twenty years after that experience, Kidwai wrote that he “didn’t know how this would play out for him at home. He was deeply afraid,” says Banerjee. As a foreigner on a student visa, Kidwai was worried about how his charges would affect his immigration status and was unable to focus on his studies while under investigation. He eventually decided to return to India before he was due to appear in court, leaving his PhD unfinished, fearing how a trial would affect the perception friends, family and colleagues back home would have of him. Years later, through a letter from a friend, he learned that the charges were dropped. That experience “really shattered his idea of freedom that he used to believe in, and stopped believing in,” explains Ghunna. “He was like, ‘If this is what freedom is, then I’d rather go back.’”

Upon returning to India, Kidwai resumed teaching history. He also started living as an openly gay man, something he previously thought to be impossible. His prior image of utter queer repression in India and the non-Western world was challenged by his experiences during the raid. “It affected him deeply and probably stayed with him for decades because he didn’t talk about it,” says Banerjee, further explaining that Kidwai was active in the 1990s Delhi gay community and gave public talks about queerness. He had a circle of queer friends, even if the scene wasn’t as established as Montreal’s. “Parties would take place in somebody’s office after hours. Everybody would get very drunk and then everybody would have sex with everybody,” said Gupta in the documentary.

Despite homosexuality still being criminalized in India at the time, many Indian queer people were able to live full queer lives. On his visits to see Kidwai, Gupta was surprised by how queer life could exist even in the repressive context of India at that time. He saw long-term couples, direct action groups and queer social groups advertised with a red rose at the entrance of cafés.

After leaving his teaching position in 1993, Kidwai co-edited Same-Sex Love in India: Readings in Indian Literature, a queer history of South Asia. Today, the book is regarded as a foundational text for Indian queer studies. It was cited in the country’s Supreme Court hearings to end the criminalization of homosexuality in 2018.

When researching Kidwai’s story, Ghunna and Banerjee realized they had found the representation they themselves had always wanted to see—and sought to create it for the South Asian queer community. Some of Kidwai’s friends came to Falooda’s first private documentary screening. “It was really nice to see what I would call the ‘old gays’ talking and being so open,” says Banerjee.

Collective members say that it was also heartwarming to see older community members interact with the younger South Asian queers who showed up for the screening. They were very moved by the intergenerational exchanges. “It really affected my perspective on how to view that kind of change,” says Ghunna. “It definitely laid out a really good framework on how to do this and create a sense of empowerment, especially for younger folks.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra