Ten years ago this month, I walked into a second-floor office on Davie Street in Vancouver and asked to be a journalist for what was then Xtra West. Managing editor Robin Perelle assigned me a fluff story about BC’s new outreach strategy for meth users, but from my days in student journalism, I knew that the best way to make the story interesting was to find the angle that would inspire outrage.

Outrage would inspire action. One of those actions would, hopefully, be a job offer.

I found an expert who told me the province’s whole strategy ignored gay men, who were the principal meth users in Metro Vancouver. I filed the story, got two more assignments, and was soon able to quit my bussing job at the karaoke bar across the street and write more-or-less full time.

Outrage was a bit of a scarce resource when I first started writing for Xtra. In early 2006, we’d already won same-sex marriage, and even the new Conservative prime minister had effectively conceded the point. “Why do we even need gay activists anymore?” is a question I’ve had to answer more times than I can count in the decade I’ve been doing this, and all too frequently it’s being asked by gay people.

Still, over the years I’ve seen Xtra continue to inspire outrage that led to action. The mass vigil after the possible hate-crime murder of Chris Skinner. The rapid progress being made on trans rights across the country. Perhaps most memorably, the movement sparked by Andrea Houston’s coverage of bans on Gay-Straight Alliances in Ontario Catholic schools, which has led to legislated protection of GSAs in multiple provinces.

Now, 10 years after I started writing here, the outrage-reward cycle moves faster than ever. To search Twitter for any of the day’s big news is to be confronted with a torrent of outrage, ranging from mildly dismissive snark, to calls for resignations, to death threats, all retweeted and screencapped and quoted out-of-context for the echo chamber that has become our biggest public forum.

Last week, queer fans stormed Twitter under the hashtag #LGBTfansdeservebetter after a lesbian character was killed on the CW show The 100. Nevermind that The 100 is a post-apocalyptic adventure fantasy where main characters die with incredible regularity. To the Twitter Machine! Announce the outrage! Create the GIFs! Collect the retweets!

Fans called for the show’s cancellation or the firing of its creator and executive producer Jason Rothenburg, surely an excessive and counter-productive solution to an imagined slight.

But that torrent of anger pales in comparison to the hate storm unleashed last week after Hillary Clinton erroneously praised Nancy Reagan’s “very effective, low-key advocacy” for HIV/AIDS during an interview at Reagan’s funeral.

Let’s not pussyfoot. The Reagans were not HIV/AIDS advocates — they were among the principal obstacles to HIV/AIDS research and services when the virus was at epidemic levels in the United States. That Clinton would make such an error is baffling, especially considering her own record of work on HIV/AIDS in and out of office.

Clinton tweeted an apology within hours, and then a longer statement outlining what her priorities on HIV/AIDS would be as president, but neither of these could staunch the flow of outrage from social media activists over the weekend. Judging by the vitriol, one might’ve thought Clinton had invented HIV, death-marched gay men into ovens and cancelled RuPaul’s Drag Race.

Actually, epic though Clinton’s blunder was, it didn’t really change anything, except perhaps lend the impression that parts of the Democratic coalition is fracturing at a time when the Republican Party appears increasingly unhinged. But much as I refuse to join the praise chorus when Trudeau does something symbolically nice but ultimately distracting and meaningless, I withhold my outrage for actual injustices.

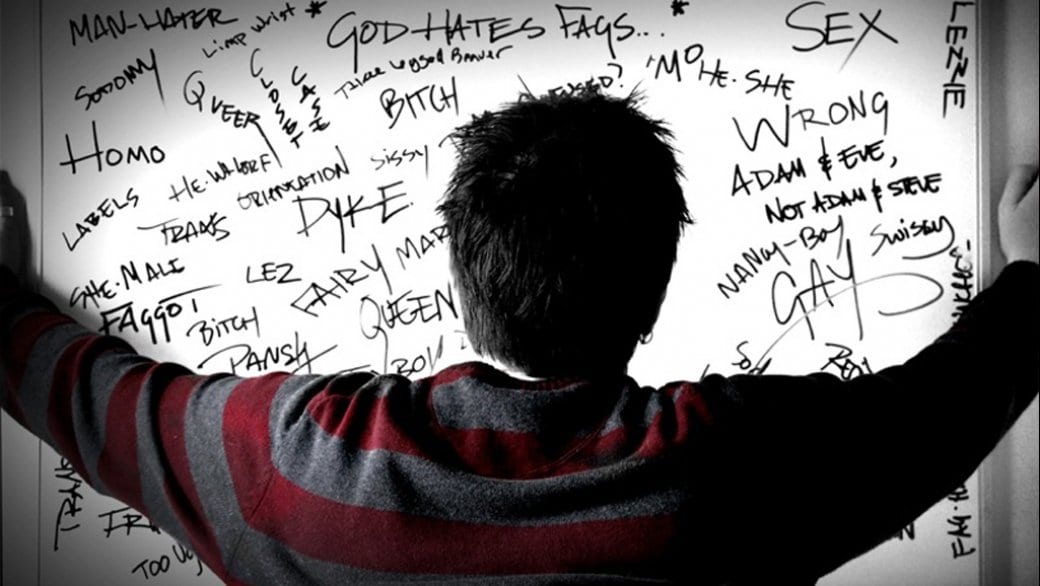

And those injustices against our community are still legion, both in Canada and especially abroad.

Outrage can be a useful tool for binding a community together to fight injustices. But, particularly on social media, the venom we spit can become fences that keep out possible allies. We snark at the ineloquent views of bigots rather than engage with them because it’s easier, and we sacrifice the opportunity to build bridges.

I’m no stranger to snark, and I definitely enjoy a funny turn of phrase. But as I enter my second decade of doing this for a living, I’d like to hope that my work is doing more to educate and engage than to ridicule and divide.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra