My femme journey is one of body, of trauma, of fashion and of community.

I was a fast bloomer; I had boobs by the age of eight and periods by 11. I could not escape the projection of womanhood onto my body, nor the sexualization that came with it.

Before I was even able to form my own sense of identity or sexual agency, my body became the target of inappropriate and unwanted attention.

The last few years of elementary school were riddled with uncomfortable encounters. At age eight, I remember a school bully telling a group of girls in my class to line up against the wall. He came along with a ruler and measured how much my butt stuck out in comparison to all the other pre-pubescent, flat-bodied girls.

Other boys licked their lips and raised their eyebrows. Other girls shot me glares or laughed. I thought we were all the targets of the boys’ perversion; it turned out my body was the object of entertainment for the entire class. My mother had attempted to instil some pride in our shapely African figures, but nonetheless I felt different, confused and ashamed.

Not long after, we were changing for PE class. The girls and I had developed a system called “the risk” where we had to find a myriad of complicated ways to get changed in the classroom without our “private parts” being exposed. This was usually a team effort; we would work together with a cute and miniature version of the radical femme solidarity I experience now.

However, one day I’d gone to school commando. A girl noticed I was growing pubic hair and screamed to the rest of the class to take a look. This would be the first but certainly not the last time I was betrayed by a white woman.

For some reason, I didn’t wish I wasn’t exposed at that moment; I wished I was a boy.

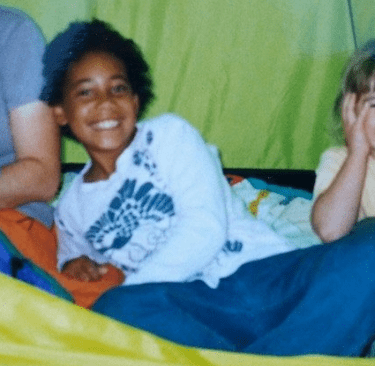

The author around age eight or nine, camping with family. Credit: Courtesy Cicely-Belle Blain

I knew that boys had no issue seeing each other’s genitals and I knew that girls (except me) wanted to see them too. At that age, I obviously had no idea that gender was not related to body parts but I craved an escape from girlhood.

Growing up, I was given a lot of freedom to make my own choices around how I presented myself. I didn’t realize it at the time, but my mum’s openness to my gender experimentation has enabled me to become a fierce and fearless femme in my young adulthood.

In contrast to school, home was a place where I felt free to explore my gender and see how different clothes or hairstyles made me feel. At school we wore a uniform which necessitated gender conformity because girls could only wear skirts or tight trousers, while the boys’ trousers were loose and comfortable.

In Grade 6, my family and I moved to a small village in France; the environment was drastically different and children there seemed far more innocent and immature. Temporarily, I enjoyed a sweeter childhood (when I didn’t have to recite my times tables in French) where I felt completely removed from the drama of city life.

In that small village, children were just children and while I sometimes felt different for being Black, day-to-day life was far more relaxed.

When I started secondary school back in London, I became victim to a lot of the pressures that young girls face to fit in. I started to wear makeup, hiked up my school skirt and attempted to walk in heels.

The author, right, in Grade 11 in London. Credit: Courtesy Cicely-Belle Blain

While now I embrace a lot of these aspects of femininity, my introduction to them was sudden and harsh. I went from living an idyllic childhood in a rural French village to being thrust into pseudo-adulthood in South East London.

I became acutely aware of how young women were supposed to behave and was quickly subsumed into that culture. I loved being back in England, but I also yearned for the simplicity that I had experienced in France.

I felt like I was playing a game of catch-up with other Grade 7 girls who had somehow prepared for the hormonal shift of high school. They had all the right clothes and shoes and accessories and most importantly . . . they looked the part.

The same girls that had been skinny and delicate in elementary school were now tall and slim and attractive. High school is about fitting in; it’s ultimately a race to fulfil a heteronormative script. I lost my carefree pre-pubescent self and became insecure; I would have described myself as ugly and fat with nappy, untameable hair. The combination of oversexualization and racism made me feel alien and inadequate.

In the raging hormonal high school environment, my undesirability was literally depressing. I was trying on a form of femininity that didn’t work for my body; I was oversexualizing myself to appeal to boys that I didn’t really want to appeal to. All the while, strict British school regulation banned nail polish, earrings, skirts above the knee, coloured bras and shiny shoes. It trapped us in a paradox of needing to conform but being punished for our femininity.

My teenage years were also plagued by unwanted attention from older men. As young as 12 or 13, I remember being asked on dates or asked for sexual favours by strangers who were at least three times my age. I think London is a city that makes you grow up fast; I was taking three buses to school alone by age 11. These experiences made me feel robbed of my childhood; I felt flattered by the attention that I saw pretty, thin, white women receive in movies yet confused and scared by the perversion of older men.

Why didn’t boys my age like me? Why didn’t I like them? The stripping of my sexual agency confined me to a forced heterosexuality that I wasn’t even sure I wanted. In Grade 7, I remember telling a friend that I was attracted to girls (Rihanna, specifically) but then closing myself off to the idea for the next eight years because I knew I did not own my body, my desires or my own sexuality.

In my late teens I finally came out as queer and really wanted to seek queer communities. My femininity was complex; partly, it was something I felt pressured to conform to as someone raised as a girl, yet it also began to feel like home. I began to associate femininity with creativity; I was excited about all the ways that I could express myself through fashion and makeup. Through femininity, I found a form of self-expression that worked for my body.

First year of university, age 18. Credit: Courtesy Cicely-Belle Blain

While some people seek a rejection of labels, I am someone who finds safety and community in being able to name my identity. At a dinner party with my new queer and trans friends, someone referred to me as “femme.” They were talking about how queer women and non-binary folks who are more feminine-presenting are often invisibilized within the queer community because they appear to be straight. This was a brand new concept to me at the time, but it suddenly felt so fitting.

I also felt overjoyed at the feeling of belonging; of being named and recognized; of being welcomed into a community. I had spent a few months attempting to wear button-ups and bowties but felt overwhelmingly disconnected from my sense of self. I thought that to be queer and non-binary meant appearing more masculine so I felt pressured to conform to this stereotype. I embraced the “femme” label because it felt so apt a description for my aesthetic and my lived experience.

I began to meet people who taught me new language to describe my gender experience and affirmed the messiness of my identity. I learned to let go of my insecurities of not being enough. I learned to undo the binaries that existed within my mind. I learned you don’t have to have a gender or a relationship to womanhood to be femme.

I realized that my femmeness did not have to be a projection of my gender but rather a community I felt at home in. I felt at peace with the way I looked because I was able to dress and present myself in accordance with my desires, my mood, my destination. I had been freed from restrictive notions of shame and guilt.

The experiences of oversexualisation that became the backdrop to my childhood, told me overwhelmingly that my body belonged to men. They did not allow me to imagine myself as a queer, non-binary femme with my own sexual freedom. Yet, here I am! I think I owe this transformation to the femme communities I have found both in person and online.

Queer and trans femmes, particularly trans women of colour, are exposed to disproportionate rates of discrimination and violence, even within queer communities. In a patriarchal society, sometimes our only option is radical self-love and caring femme communities.

I am continually inspired by all the fat, Black femmes I see on Tumblr and Instagram who are so raw and vulnerable in their rejection of white beauty standards. Our bodies need to be seen to be accepted and I am excited to be part of shaping a future where young femmes see value in their bodies and take ownership of their blossoming sexualities.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra