I was so angry I couldn’t focus on the game I was playing.

My phone buzzed. I paused my game to reach for it and glared at the small screen before unlocking it.

False alarm. A friend had sent me a silly puppy GIF on Facebook Messenger. I chuckled with relief and put my phone down to resume my game.

My phone buzzed again.

This time it wasn’t a friendly message.

My Facebook notifications told me that my latest comment had garnered another nasty reply. I had spent the last 30 minutes in a heated, painful argument about racial diversity in media. I had never even met the guy I was fighting with. A mutual friend had made a Facebook post on the topic and we both just happened to comment on it.

The stranger’s latest comment defending the lack of racial diversity in popular media was even longer than his last. My rage reignited. As I furiously thought of my own response, my phone buzzed a few more times to let me know that other people had joined in. An hour was wasted with both sides refusing to give in.

Why was I spending so much energy fighting a complete stranger online? It’s strange to think that the internet used to be my haven.

*

It was a rainy Sunday afternoon in April 2008 and I had just survived my fourth Canadian winter.

I was a university student living in a two-bedroom apartment with my family in East Vancouver. Everyone had the day off and both of my parents were home. Down the hall, I could hear Mama getting dinner ready while Filipino church music from the CD player radio filled the rooms.

I shut my bedroom door. I wanted a bit more privacy. But since my door had no lock, closing the door would have to do.

I turned and stepped back to my desk. I put aside the genetics textbook I was supposed to be interested in and pulled out my art binder. I glanced back at the door. I really didn’t want to be disturbed again.

The previous night, my mom had barged into my room and caught me working on my latest art piece. She froze upon seeing my sketch. I could tell she didn’t know how to react. It was almost like she had caught me with porn.

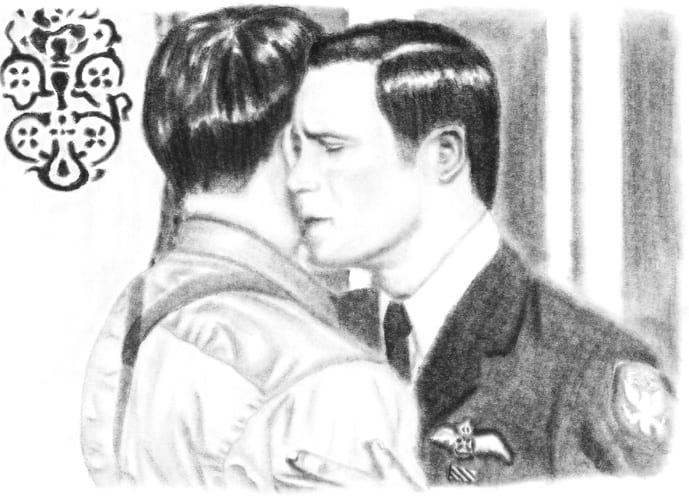

The piece wasn’t pornographic, but it was definitely queer. I had drawn two male scifi characters from the show Torchwood in a romantic embrace.

Mama didn’t start an argument, but she didn’t discuss the piece either before leaving. I had been out of the closet for a year and she was still learning how to be supportive of her gay son. That moment was like a litmus test to her comfort levels.

The author’s Torchwood sketch. Credit: Courtesy Justin Saint

Confident that my family was too busy to invite themselves in, I leaned over and turned my desktop computer on.

As it booted to life, I pulled the new sketch from my binder. Hints of graphite pencil wafted up to my nose and the passion, longing and relief that I had poured into my work came flooding back to me. I quickly scanned the sketch and uploaded it to DeviantArt, an online community where artists created digital galleries to display and share their work.

As I started to write a description for my piece, I suddenly realized that my parents hadn’t entered my room at all since my mother had seen the piece the night before. I was enjoying a sense of privacy that I hadn’t felt in a long time.

That taste of privacy made me a little bit daring.

I had been raised to never speak ill of my parents no matter what they did. Talking badly about your Filipino-Chinese parents was considered disrespectful and ungrateful. It was one of the worst things a child could do to a parent.

As a result, I was usually very private about my family and barely spoke about them at all. I was shy, reserved and tried to avoid anything that might result in conflict. Until that day.

That day I wrote a small public remark underneath my sketch on DeviantArt that hinted at the lack of privacy I was feeling at home.

“If you want to stop your parents from barging into your room unannounced at random intervals, draw something they don’t want to see.”

My Canadian best friend Keegan was the first to interact with the online post. He caught the sarcastic remark about my parents immediately. He quoted it, saying “Lol. I need to try this.”

Besides Keegan, I also had some Filipino friends from Catholic school who followed my work. I was a little bit worried that one of them would start an argument. The nature of the piece and my little remark were easy targets for a fight. But if any of them had seen the piece, none of them interacted with it.

Then a complete stranger, a user who went by the online name RainyxDay, randomly stumbled onto my sketch.

She was an American photographer with her own gallery on DeviantArt. She was just as passionate about the show Torchwood as I was. She left a glowing comment on my sketch, which led to excited messages back and forth. I knew very little about her but we became instant friends.

As other Torchwood fans found and interacted with my piece, I watched a community grow around me.

RainyxDay and I joined a Torchwood fan club. Suddenly it didn’t matter that none of my real-life friends watched the show. I had friends online who shared my passion and my enthusiasm.

I needed that haven. Outside in the real world I was battling depression, immigrant culture shock, and living through a difficult year of coming out.

I had been expected to grow up to be a successful doctor, scientist or mathematician. My lack of interest in dating had previously been applauded as a smart move as it allowed me to focus on my studies. When it was revealed that I had no drive to pursue either the sciences or women, every single movement I made fell under scrutiny. I never knew which little mistake would lead my father into to an hour-long sermon about how pathetic I was. My life was a minefield planted with good intentions.

Justin Saint. Credit: InkedKenny/Xtra

DeviantArt became a magical place of positive social interaction. Our shared geeky interests, our mutual understanding of each other’s challenging lives, had brought my online community together. Many of us had trouble “fitting in.”

On DeviantArt, it was possible to forget the stresses of the real world for a few hours and just be with friends. It was a space where we could explore the thoughts and emotions of a difficult experience like coming out, family pressure, or being an immigrant. While it was still possible to run into someone who was rude or aggressive, those encounters were few and far between.

And if I was still figuring out how to refine my online presence, so was everyone else.

Back then, most online users still remembered a time before the internet. We were all newcomers, online migrants learning how to behave and interact in a young but rapidly evolving digital world.

Nobody had ever taught me how to behave online. I was the first person in my family to actively use the internet. By the time my friends and I were being taught to type in elementary school, we already had a list of geeky websites that we frequented.

I learned how to act online by observing how other people behaved.

And there I was, six years later, having an online argument with a guy I didn’t even know on Facebook.

*

It was easy to give into my rage.

I had been defending myself from attacks on multiple fronts. While the subtle jabs and aggressive insults were from people of different backgrounds, the message was the same: they wanted me to know that I was different.

And I wanted to squash this stranger.

I finally had the confidence to speak my mind and I was determined to use it. It felt good knowing that my opinions were being read and dissected. I could tell this stranger was reading my every single word, looking for a flaw or mistake in my argument that he could use to his advantage. Which was fine, because I was doing the same thing to him.

I knew other people were reading our comments too. The comments section was my online pulpit. I was drawing allies to my side. Their likes and responses gave me validation.

Some people repeated previous points and I could tell they hadn’t bothered to read what had already been said. But I didn’t care: we had strength in numbers. Each new comment was fuel for my righteous fury. We were louder. In my mind, it felt like we were definitely winning.

In the years since my early posts on DeviantArt, I had slowly shifted into the habit of writing politically contentious posts on Facebook and other social media. It didn’t matter if the topic was geek culture, LGBT issues or actual politics. It didn’t even matter how much or how little I actually knew about the topic. People paid attention to my bubbling emotions. It was nice to know people agreed with me.

Inevitably, my posts would also attract people who didn’t agree with me. And the fights would begin again.

Online bickering became the norm for me, playing out on repeat in increasingly vicious cycles. Until one day I realized that my online presence was attracting all this hate and negativity.

Credit: InkedKenny/Xtra

I had set the precedent that it was totally acceptable for complete strangers to fight on my Facebook wall. The energy required to sustain all that anger began to wear on me. I wanted to stop but I was afraid that letting go meant losing my voice.

One day while playing a multiplayer game online, a teenager told me to kill myself because our team lost. I shrugged it off and moved on. A few days later, it happened again.

This new stranger let me know through uninvited comments that he didn’t like the character I was using. He spent more time hurling homophobic insults at me than actually playing the game. Not surprisingly, our team lost. He then told me to kill myself as well.

Suddenly it became normal to encounter that level of vitriol at least once a day.

I tried to ignore them. These people were eager for a fight. They were burning with anger and waiting for someone to notice. They wanted someone to engage with them. I knew that rage all too well.

Eventually, I got exhausted trying to sustain a thick skin during my downtime. That thick skin was something I had needed to grow to survive my father’s anger and disappointment at my coming out. I had spent years trying to get away from that rage. And here I was willingly entering a space where those shields were once again necessary. I was too worn out to keep my defences up. Especially when I was just trying to have fun.

I found myself disconnecting from my virtual community. Unmoderated online rage had seeped into all my social circles. It didn’t matter if I was interacting with geeks and gamers, the LGBT community, or simply on my personal social media. My worlds had swapped roles. It was now the physical world that offered respite from the minefields of online trolling.

Suddenly, expressing myself online also meant defending myself online. Nothing I had ever faced or learned in the real world could have ever prepared me for such increasing levels of contempt and hostility.

I stopped playing multiplayer games altogether. I also modified my social media posts to attract fewer threats and insults. I made a personal rule to avoid posting about social issues as much as possible. Heavy conversation was best saved for face-to-face interaction.

I asked some friends — established writers, artists and performers with fairly significant online followings — how they dealt with the negative interactions that often bombarded them. They urged me to stop reading the comments, to choose my battles wisely and, above all, to remember that creating art is about exploring my own inspiration and to never let anyone’s hate silence my passion.

The 2001 video game Metal Gear Solid 2 predicted a dystopian future where junk information had grown at such an alarming rate that it had overtaken the recording of history and culture. “Truth” was modified to fit what was most convenient. Multiple “truths” could exist at once, supposedly promoting free speech and avoiding conflict. Nobody could ever be called wrong, but nobody was ever right. A society founded on accumulated trivial content brought human progress to a crashing halt.

Are we slowly entering that dystopian future? The internet has been around long enough that there are active online users who don’t remember a time without it.

At a recent gamer convention, I found myself at a loss one afternoon when a young gamer told me that aggressive behaviour was just a normal part of his online experience.

“That’s just how people talk online,” he said cheerfully. “When someone says they want you to die, they don’t actually mean it that way.”

Where not so long ago I had found solace and support online to embrace my true self, this new virtual experience was filled with unchecked rage — and this young gamer just accepted it as normal behaviour among strangers.

I watched as he continued playing his game, shouting his own set of insults in the middle of a noisy show floor.

Maybe that dystopian future isn’t coming. Maybe it’s already here.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra