This story is part of “Still Fighting,” a series exploring the past 50 years of LGBTQ2 activism in Canada.

For nearly a century, Canada had laws on its books prohibiting buggery — then the legal term for anal sex — and gross indecency, a charge that was used to prosecute sexual activity between two men. But on June 27, 1969, the country’s Criminal Code was amended to include various reforms, chief among them what’s been dubbed the partial decriminalization of homosexual activity. That meant that anal sex and other displays of queer affection could occur, but only in private by consenting adults who were 21 years of age or older.

Today, those reforms are often considered the kickoff to the past 50 years of LGBTQ2 activism, which has crystallized the rights of queer and trans Canadians. It seems crucial to commemorate that moment, as well as the many that have preceded and followed it.

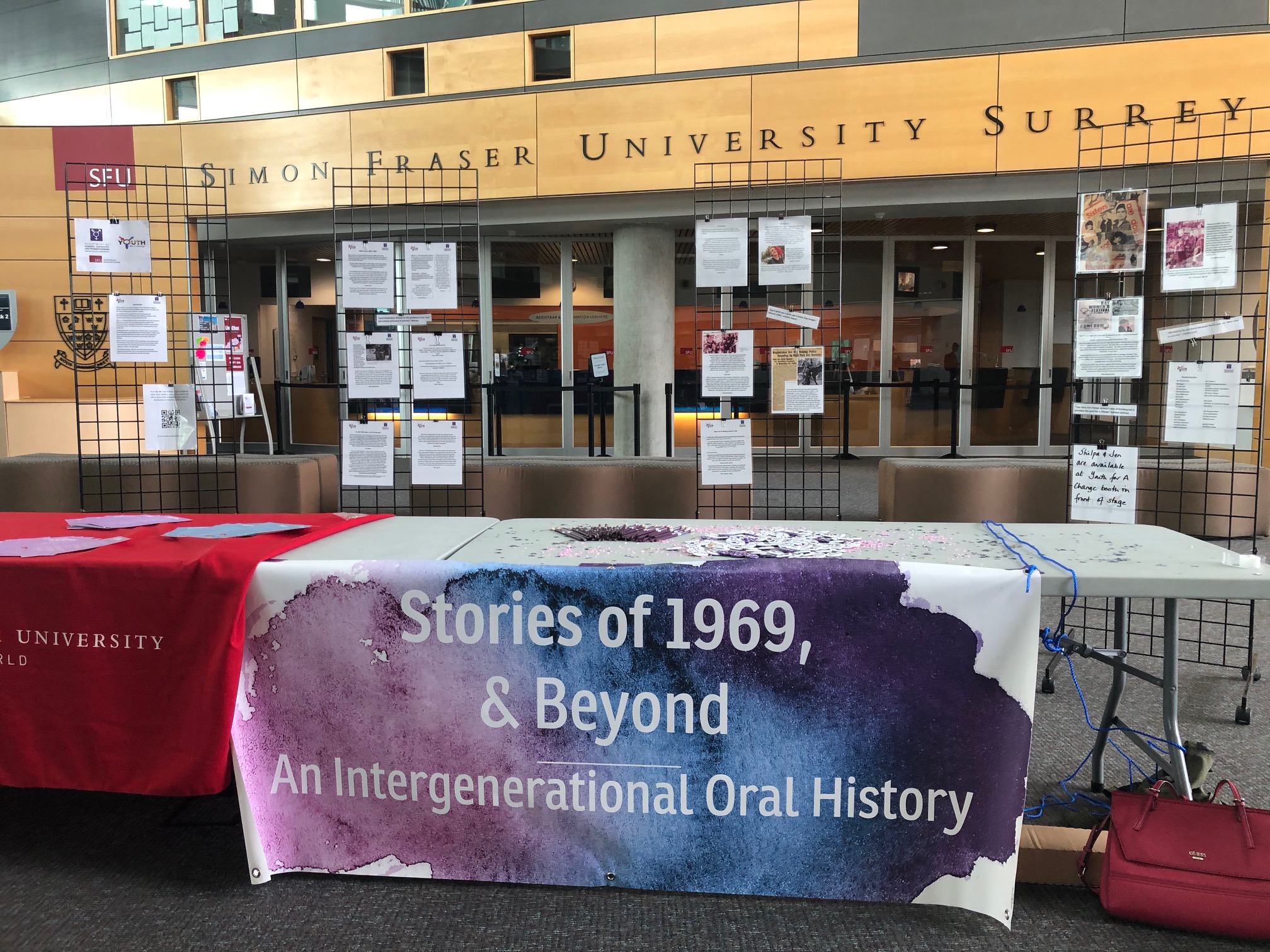

So much has taken place in the last half-century — the legalization of same-sex marriage, the enshrinement of legal rights for trans Canadians — that we need to share with the next generation of youth and young activists. That’s why, in partnership with BC’s Simon Fraser University and the LGBTQ2 activist group Youth for a Change, I helped create “Stories of 1969 and Beyond: An Intergenerational Oral History Project.” For its launch in June at city hall in Surrey, BC, we found voices from across the generational spectrum, ranging from locally based LGBTQ2 folks who remembered the reforms of 1969 and beyond to young adults who recorded and responded to the stories they heard from our older participants.

The project displayed at the Simon Fraser University Surrey Campus in June for the Surrey Pride Festival. Credit: Shilpa Narayan

Through our interviews for the project, it became clear that the 1969 Criminal Code reforms, despite being billed by the government and the media as the end of LGBTQ2 criminalization, were never a satisfying solution; they were just a beginning. While some queer and trans folks we spoke with expressed joy at the removal of certain acts from the Criminal Code, others shared stories of continued harassment and discrimination, some of which they experience to this day. Our findings are straightforward: Activists, both old and young, agree that we have a long way to go.

Looking back on 1969, longtime activist Ellen Woodsworth agrees that the Criminal Code reforms were a mere step toward LGBTQ2 equality. It wasn’t until she began organizing with the national, coast-to-coast Abortion Caravan in the 1970s (during which time she chained herself in the House of Commons in support of women’s right to choose) that Woodsworth came out publicly as a lesbian. “I was fed up with the politics of the left that didn’t include women,” she remembers. “But it certainly did not include gays and lesbians [either].”

Vancouver activist Donna Dykeman also adds that credit should not just be given to our government, but to the community members who mobilized for the legal changes necessary to improve LGBTQ2 rights. “It wasn’t one politician, one move, and everything was fine, because in no way does partial decriminalization mean a human rights achievement,” she says. “And of course, once [those changes] happened, the work had to continue on many levels.”

The author at the launch of the project. Credit: Shilpa Narayan

Those interviews and others informed further tough conversations between our older activists and LGBTQ2 youth. Our younger participants asked questions that didn’t always lend themselves to easy answers: They wanted to know what the LGBTQ2 activists who came before them had endured. How has life changed for those who experienced the past 50 years of LGBTQ2 activism? Did the older participants think the 1969 reforms made a significant difference in their lives?

The responses were often surprising for the youth involved, many of whom felt unaware of the hardships their predecessors had faced. It’s why we also asked them to record their reactions for our project in order to bring our work full circle, bridging the gap between generations of activists.

The result was a different way of looking at history, through the eyes of the next generation that will be responsible for the activism to come. The interviews were packaged into an educational exhibit that has travelled through BC, and a podcast was created to highlight our findings for those unable to experience it first-hand.

My hope is that the project will demonstrate the significance of oral history passed on from generation to generation. So much of queer history is never taught in school or featured in textbooks. To learn about the pivotal moments in LGBTQ2 Canadian history from those who were there fighting motivates youth to carry the torch for our country’s queer and trans elders.

To listen to the podcast and explore more of “Stories of 1969 and Beyond-An Intergenerational Oral History Project,” visit youth4achange.com

This story is part of “Still Fighting,” a series exploring the past 50 years of LGBTQ2 activism in Canada.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra