As a trans kid growing up in 1980s Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), I first encountered transphobia in Grade 6. I buried the memory for years, but it kept resurfacing, like a swarm of blackflies circling for blood. The resurgence in queerphobic rhetoric from today’s right-wing politicians brings it back with a potent sense of déjà vu.

I lived through a “Don’t Say Gay” era in 1980s/90s NL, one in which gender nonconforming children faced violence in school and in which queer teachers lived in terror of being outed and fired. One in which the curriculum was silent on sexuality and gender identity. The silence of our own “Don’t Say Gay” era didn’t protect young ears from controversial ideas: it screamed homophobia and transphobia, and irreparably harmed generations of kids and adults alike.

1987: Grade 6

I remember how it started: one of those idle classroom discussions sparked by someone asking the teacher where he had gone away to the week before.

“Toronto,” he replied.

We gasped. Toronto! Dreams of skyscrapers and bright lights filled our young, preteen, Newfoundlander heads. “Tell us about it,” we begged—“regale us with tales of the mainland!”

Our teacher shook his head. “It’s a horrible place,” he said. “A terrible place. A place where men wear dresses, and women kiss women …”

He spent the next half hour working himself into a fury about the queers of Toronto. He hit them all—gay men, lesbians, trans people—raging against the wickedness and perversity of the big city.

Credit: Courtesy of Rhea Rollmann

I remember the glint in his eye, the snarl in his voice filled with a combination of mockery and revulsion. I don’t know what happened to him in Toronto, or wherever else he got his homo- and transphobia. But the hate in his voice was visceral.

Even at that age, I instinctively knew there was something wrong with a teacher who would speak about anyone in that tone. I must have worn my skepticism on my sleeve, because at one point he turned on me.

“They’re disgusting and evil, aren’t they?” he demanded, calling me out by name. “Do you disagree?” He eyeballed the rest of the class, ready to mock me if I did.

I knew better than to disagree, and shook my head vehemently, hating myself for it an instant later. I tried to shrink into my desk for the remainder of this impromptu class in late ’80s bigotry.

It was only later, replaying the scene in my head at home, that my sense of discomfort hit me at a different level. I realized he was talking about people like me.

When I was in Grade 6, there were no public schools in NL. When the province negotiated its confederation with Canada in 1949, the all-powerful churches drew a line in the sand around education, and Canada caved to their demands: Christian churches would effectively control our education system. It was written into our Terms of Union with Canada. There were no non-religious public schools in the Newfoundland I grew up in.

It remained that way until 1997. Different churches had their own school systems. I attended what was known as a consolidated school: an amalgamation of Protestant denominations. It was the most liberal of the bunch. But until this system was abolished 25 years ago, schools remained outside the purview of our provincial human rights system, and teachers had little recourse if they were fired for violating the tenets of their religious school boards. Not only did this keep most queer employees in the closet, it also emboldened homophobes like my Grade 6 teacher.

I had realized I was trans two years earlier, in Grade 4, though I didn’t know the word until much later. It happened during another of those lively classroom conversations: a bunch of us gabbing with the teacher about what we wanted to be when we grew up. As I imagined myself in the future, I suddenly realized there was no version of myself I could imagine as an adult man: every future me was a woman. I was floored, and confused, but socially savvy enough to tell no one.

The internet then existed only in remote computer labs, and my phobic, frightened teachers were no help in figuring things out. Every day I scoured the newspaper, where every few months there would be a titillating story about a trans celebrity in some faraway land. I slowly put two and two together. I’d never heard the term “transition,” but came to understand that somewhere far away was the means for me to become the woman I increasingly saw myself as.

But that Grade 6 teacher taught me something else about the world: trans celebrities like actress Caroline Cossey and tennis star Renée Richards and all the others I read about in the newspaper may have been able to dwell in a state of exoticized otherness, but everyday trans folks risked the contempt of people like my teacher. I still didn’t know the term “transition,” but my inchoate hopes took a beating that day.

Unlikely heroes

Credit: Courtesy of brian Campbell

Don’t take the wrong message: this isn’t about the backwardness of a rural society. Today, NL is one of the most gender-diverse provinces in Canada, and it’s now easier for NL-born residents to legally change their gender marker than it is for Ontarians. These days it’s Ontario where governments are trying to roll back vital, life-saving changes to school curricula. Bigotry comes from policies, not places. But my sense of place is forever marked by the experience of growing up in what was effectively a “Don’t Say Gay” school system.

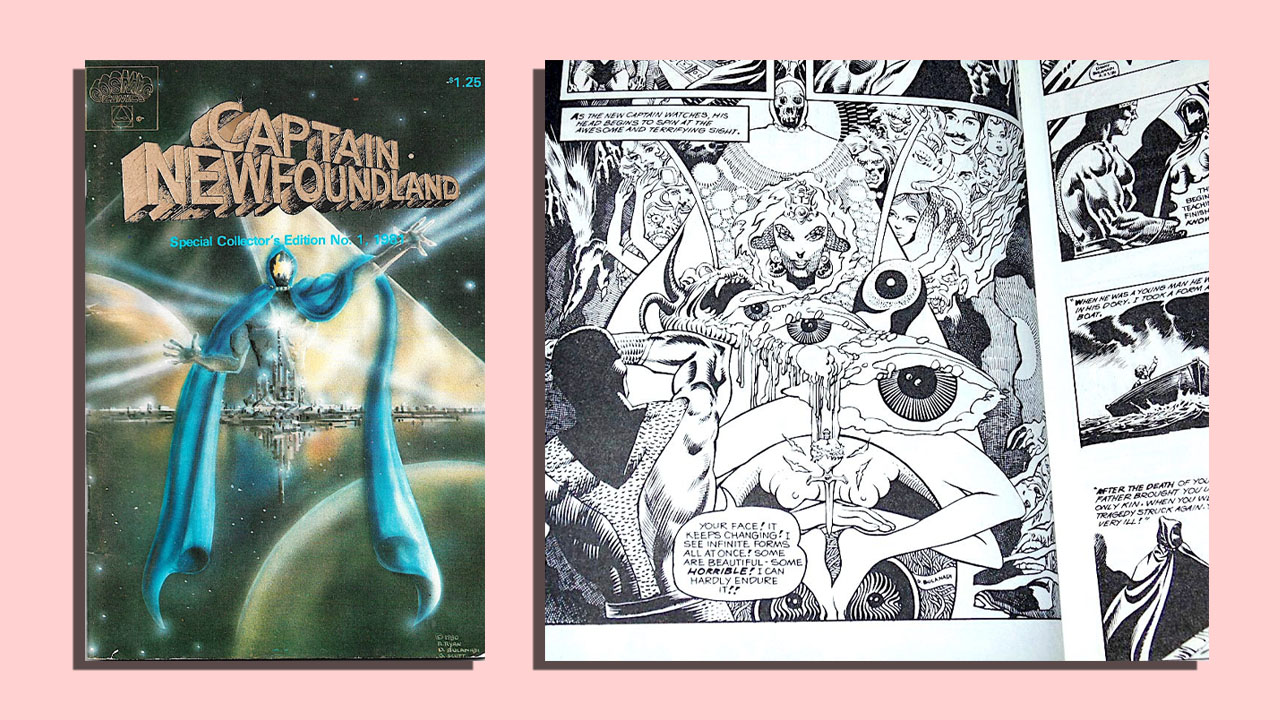

Growing up in the quirky space that was 1980s Newfoundland wasn’t all unpleasant, even for a trans kid. In a province where most households had only two television channels, we weren’t exposed to a lot of gender-diverse role models. But we did have Captain Newfoundland’s iconoclastic pantheon of superheroes. Yes, there is a Captain Newfoundland. Created by millionaire media mogul Geoff Stirling in the 1970s (along with his son Scott and artist Danny Bulanadi), he appeared in local comic strips as well as the odd bit of late-night television psychedelia. I read the strip religiously on a weekly basis in the back pages of the Newfoundland Herald, a sort of tabloid-cum-TV-guide.

Captain Newfoundland was an Atlantean who rescued drowning children, fought off alien invaders and got friendly with time-travelling Vikings (the island is the tip of a sunken Atlantis, don’t you know?). I’ll never forget the panel where he reveals himself to his son (the immature, ever-in-training Captain Canada) in his full array of physical forms: both male and female. Here was a gender-bending astral traveller, and this opened up myriad possibilities for a young trans kid.

The female superheroes of our Newfoundland multiverse looked binary on the surface (acclaimed fantasy artist Boris Vallejo was commissioned to produce some of the art), but they were potent role models for a trans girl: wise Atlanteans who travelled the astral plane and transcended physical embodiment. Mademoiselle and Night Wind preached about the power of emotion and dream states, while the Silver Warrior led an army of mermaids against the evil King Sat’n. The New Age philosophy dripping from each and every weekly strip underscored a message about transcending and reshaping our bodies to better align with our souls; it was vague, but reassuring.

I personally never encountered Captain Newfoundland while walking along the breaking waves at the beach (his favourite earthly haunt: he enjoyed philosophizing with fishermen). But the message he preached was one that supported me on a deeper level, and I’m grateful for it. His mantra still echoes: “To thine own self be true.”

High school

Credit: Elham Numan/Xtra

By the time the ’90s rolled around and I was in high school, a lot had changed. Our teachers were growing bolder; some of them were queer or had queer friends and hated the system too. Inevitably in health class some student would ask: “Miss, what about gay people?” It was a question without a focus, begging for a lesson that wasn’t in the curriculum. The teacher’s response would usually be something like: “Just be glad you’re not in a Catholic school!” and we’d spend the rest of the class sharing lurid gossip about poor Catholic students being beaten by their teachers. Shaking our heads at Catholic intolerance, I realize now, was a deft method of distracting us from the prejudice in our own schools.

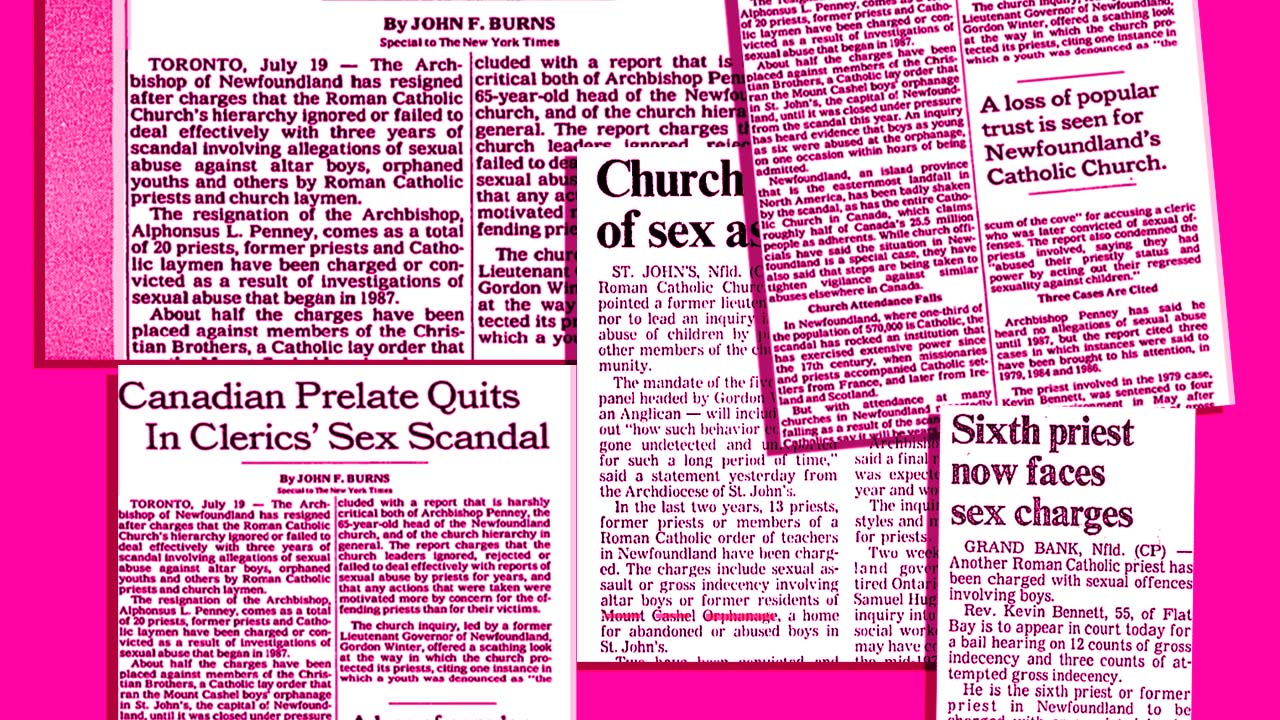

The backdrop to those high school years was what today is known as the Mount Cashel scandal. The word “scandal” belittles the impact it had on our province: it shook the socio-political fabric of NL and continues to do so today. Mount Cashel was an orphanage in St. John’s run by the Catholic Christian Brothers, where generations of young boys were sexually abused. Efforts to expose the abuse were covered up by police and politicians for years. When the “scandal” finally broke, politicians and church leaders tried to blame it on “homosexuals.” Advocates fought back against this messaging, which is so evocative of today’s “groomer” rhetoric deployed by conservative politicians. Queer activists and allies pointed out the so-called scandal wasn’t about homosexuality, but about the impunity of powerful men and the patriarchal institutions (churches, police) they controlled. In the short run, the scandal may have fuelled homophobia and intensified police and media surveillance of gay men, but in the long run it finally shook the iron chokehold of the church on provincial politics.

But as a high school kid, I barely registered the scandal playing out on the nightly news. I had my own issues to deal with. I had a solid group of friends and an active social life. But unbeknownst to any of them, I was seriously considering transitioning.

I had finally come across the term. The internet was still in its infancy in the early ’90s, but I fell in with a group of geeks and got online earlier than most. I made a furtive beeline for the chat rooms, and found my people: trans people, thousands of them, all across Canada and the U.S. I observed and learned. I discovered the term “transition,” and now had language for my aspiration. But how to go about it?

What I learned didn’t sound promising. At that point, the medical establishment had an iron gatekeeping hold over transition in Canada. Access was controlled by local psychiatrists as well as institutions like the Clarke Institute and the Canadian Association for Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto, which had to approve requests for publicly funded surgery. They medicalized transition, and applied a hefty dose of misogyny in the process. Applicants had to acquire “lived experience” as the “opposite gender” for at least two years (often more) before being allowed to medically transition. If this sounds ridiculous, it was (this regime lasted until CAMH restructured its programs in the early 2010s; our province stopped using their services in 2019). “Lived experience” was defined through a misogynistic, patriarchal gaze, which considered femininity or masculinity through a caricature of almost Victorian-era values. And there was zero tolerance for anyone unwilling to conform to binary archetypes. I came across trans women in my hometown who “lived as” women for two, three, five years, and still weren’t approved for hormones or surgery; in some cases they finally detransitioned in despair. In the chat rooms, trans people across the country shared advice for those about to have their transness evaluated by psychiatrists: collect photos of yourself in frilly dresses, practise walking in high heels, pretend you have a boyfriend, don’t talk about professional ambitions. Trans people knew femininity wasn’t defined that way, but had to pretend in order to get past the misguided and transphobic medical gatekeepers.

For those of us in a province located on the periphery of Canada, all those trips to and from Toronto to parade in high heels in front of psychiatrists came at a significant cost. For a high school kid whose weekly allowance covered a handful of chocolate bars, the prospect seemed unimaginable. I knew my best hope was to leave the province, and move to Toronto or Vancouver like other trans Newfoundlanders had done. I applied for scholarships at the University of Toronto, and even wrote the SAT. But all to no avail; the only post-secondary education I could afford was in Newfoundland.

Unbeknownst to me then, there were progressives in the medical system fighting the aforementioned process, arranging surgery and hormones against the strictures of the establishment. But none of this information was widely available. Seeking it out was a gamble. You might find a supportive doctor who could help you. Or you might wind up threatened with incarceration in a psychiatric hospital. I heard stories of both.

Frilly skirts and makeup have never been part of my femininity, and as a young teenager, I had no intention to devote two to five years of my life to a misogynistic charade that seemed to serve no purpose other than titillating psychiatric gatekeepers. So I shut the door on those hopes again, and off I went to Memorial University of Newfoundland, determined to live the best cis life I could.

2000: University

As the ’90s dragged on and the millennium approached, things were changing. NL’s denominational education system was abolished by Brian Tobin, a young premier who had the clout and guts to take on the churches. The same premier finally added sexual orientation protections to our provincial human rights code, boosted funding for abortion services and even endorsed same-sex unions.

Credit: Pamphlets courtesy of Rhea Rollmann. Elham Numan/Xtra

Meanwhile, a new generation of genderqueer activists was challenging the medical establishment. I met some as an undergrad. Liam was one of them: a young, happy-go-lucky punk who made “leather” jackets out of spray-painted inner tubes. We gravitated toward each other. We traded photocopied excerpts of the work of Leslie Feinberg and Kate Bornstein (two of the trans and non-binary writers found in a brand-new section of Bennington Gate—a local independent bookstore—daringly labelled “Gender”). We discovered gender was a construct. Neither of us was out as trans at the time. In time, Liam quit university, moved to Toronto and transitioned.

But I wasn’t ready yet. With transition still gate-kept by a misogynistic medical establishment, I balked. At age 25, I teetered on a very dark edge. I’d been in a serious relationship for three years, and almost came out to my partner. Night after night I practiced the coming-out speech I was both desperate and terrified to give. But I never gave it. The institutional and social barriers still seemed insurmountable, and the medical possibilities uncertain. Two genderqueer activists I was close to had died by what appeared to be suicides, and this underscored for me the seeming hopelessness of trying to take on the stubbornly intractable gender regime.

When I decided not to transition at the age of 25, I also expected I wouldn’t live long. I recognized that the older I got, the more dysphoria and regret would set in, and I anticipated I would eventually lose the fight like so many of the other trans people I had known. I felt it was not a matter of if, but when. It’s a strange thing to accept your own inevitable demise at such a young age. I wonder how many other trans folks are going through a similar process today in Republican-controlled U.S. states (and elsewhere).

Mid-2000s: Internalizing transphobia

One of the things that kept me going was throwing myself into activism. But being a closeted trans, feminist activist was fraught. TERF-ism was on the rise, and as someone who was seen as a man, I was afraid to call them out on their violent ideas. I had some idea I could be a bridge between TERFs and the trans community. I think for a while I justified my own internalized fear of transition with this strange notion. I accepted my own second-class status as the woman I was afraid to come out as, and felt other trans women were excessively forward in their demands to access women-only spaces. All the transmisogyny I’d witnessed and internalized growing up led me to believe that trans women like myself were indeed somehow second-rate women. Yes, I—a trans woman—had internalized transphobia.

One of the things that kept it internalized for so long was the clever manipulation of TERFs. I remember sharing the stage at an anti-sexual assault rally in the mid-aughts with the crème de la crème of Canadian TERFs. I had a stunning realization that day, when I realized these TERFs were treating me better (as an ostensible cis man) than they were their own fellow cis women. This is something I’ve noticed a lot in TERF circles: a sort of accommodating deference to the male TERF allies who often become the most outspoken promoters of transphobic hate.

It wasn’t until later, when I began transitioning myself, that I began to move beyond this and realized the ways in which my own personal experiences of transphobia growing up had truly damaged me. That Grade 6 teacher had imprinted a pattern of self-hatred and internalized transphobia that was reinforced by institutional gatekeepers, by a lack of legislative protections, by TERF rhetoric.

2010s: New era, new challenges

It wasn’t until the late aughts that I finally made it to Toronto, for graduate school. There, I again considered transitioning, more seriously than ever. Institutional barriers still existed, but it was a different landscape from the one I’d grown up in. Social barriers were dissipating rapidly. What held me back this time was the feeling that I had waited too long. I knew the effect of hormones diminished with age, that surgery became riskier. The trans people I saw living their best lives were all younger than me. I felt a sense of having been born at the wrong time. Medical advances had made transition tremendously safe and effective; laws were more protective of trans people too. If I had been born a decade or two later, I wouldn’t have hesitated. But the ageism of our culture held me back.

Many queer spaces—bars and club nights—remain predominantly young-adult-oriented. On social media, new languages and hierarchies emerged, stratifying those wrestling with their identities. Newly transitioning folks were (and are) often referred to by terms such as “eggs” or “baby trans,” ostensibly cutesy and endearing phrases that are also dismissive and de-legitimizing, implying immaturity and imposing a sort of transition-based seniority. The creative expressiveness of queer youth culture is to be celebrated, but also tempered with an awareness of the ways it can serve a gatekeeping function in its own right.

Ageism is real in queer and trans culture, and led me to question the possibility of my own transition at a time when everything else finally began to align.

Then one day I came across an article about older trans people—much older than me, trans people who were in their 60s to 80s when they began transitioning. It helped me realize two things. First, if folks were transitioning in their 80s, then there was no such thing as a satisfying cis life for a trans person. I’d always assumed that if I just remained in the closet long enough, cis life would become bearable. And seeing the joy these people experienced with their transition—no matter what age—made me also realize happiness was still achievable. I’m glad I read that article, because otherwise I might have languished for another 10 or 20 years before realizing the inevitable.

Credit: Courtesy of Facebook; Elham Numan/Xtra

When I came across the article, I had just moved back to NL. Thanks to a combination of progressive doctors and even louder activists, a lot had changed in a short space of time. NL brought in human rights protections around gender identity and expression in 2013. In 2016, a clinic opened in St. John’s with an informed consent model for hormone access. In 2019, NL finally removed the requirement for trans people to travel to Toronto to be reviewed and receive the stamp of approval from CAMH before we could access surgery. NL also simplified the process of changing legal name and gender—no questions asked.

People often treat this as a matter of policy reform, achieved by advocates and lobbyists. They certainly helped. But it was a victory by trans people, and it came at a tremendous price. Many did not live to see it. I’ve spent the past four years researching NL’s early trans activists for a forthcoming book on the province’s queer history. Researching that history is a weighty undertaking that exacts a psychological toll, replete as it is with lives lost to transphobia and other forms of violence. But their struggles made life possible for us today.

People often find it strange that I transitioned after leaving Toronto, but I think I needed the familiarity of home to ground myself through such an identity-shifting experience. And there was something satisfying about transitioning in a place where authenticity had been so long denied.

To be honest, it’s hard to write these words. Growing up, I absorbed a fierce pride in Newfoundland identity, and it feels like a betrayal of sorts to look back on things so critically. But I realize now the real betrayal came from the adults who allowed these regimes to go on as long as they did. And this is something we don’t talk about enough. The barriers faced by queer and trans people here weren’t built in; they were erected by powerful institutions like churches and the politicians they controlled. That’s why it’s difficult to watch the ongoing tide of transphobia gripping large parts of the world, consuming political and cultural institutions that ought to know better.

I’m still proud to be a Newfoundlander, but today that pride is centred not in what we were, but in how we’ve changed (while acknowledging there’s a lot more work to be done to make gender-affirming care accessible, especially in rural Canada). Even our hockey teams have proudly embraced gender self-identification.

And times have changed. Earlier this year, students at Menihek High School in Labrador City organized a walkout in support of a trans classmate who was denied access to a washroom in violation of school policy. The most inspiring part of that story wasn’t the scorn that rained down on school officials for their act. It was the calm, matter-of-fact confidence of a new generation of openly trans, non-binary and gender-diverse teenagers, proudly self-identifying on provincial media.

They, I realize, would have put my Grade 6 teacher in his place without batting an eye.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra