To be arrested and convicted for a crime one didn’t commit is something that most people experience only in nightmares.

To be imprisoned for that crime in one of the world’s most notoriously barbaric prisons makes the nightmare even more Kafkaesque.

But it wasn’t a dream for Paul Ciceri, a transplanted gay Canadian living in Florida. It was an all too real experience that dragged on for nearly three years.

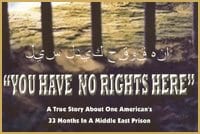

The Guelph, Ontario native spent 33 months in Al Wathba, a prison in Abu Dhabi and one of the most infamous in the Middle East, known for its human rights abuses, lashings, and deaths by stoning. Ciceri writes of his harrowing experience in his newly released book, You Have No Rights Here.

“I was living in the Middle East and working as director of marketing for some sheiks who owned the franchise rights to ELS Language Centres [that teach English as a second language] in the Middle East and North Africa,” explains Ciceri from his home in Key West, where he lives with his partner.

“Before going overseas I had been a member of LGHEI [Lesbian and Gay Hospitality Exchange International] and had met a lot of wonderful gay people worldwide at my home and at theirs. I had kept in touch with one from the Far East and in the summer of 1998 we had agreed to meet for two weeks in Greece for a vacation.

“From the moment we met,” Ciceri continues, “it was obvious that he had adopted a new, strong anti-American attitude. It wasn’t your typical ‘I like Americans but not the American government.’ It was ‘I don’t like Americans and America.’

“This vacation was just a month after the US had retaliated for the bombings of its embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam and he thought Americans were warmongers because of the military response, albeit very limited in scope,” he notes.

Two days into the vacation Ciceri’s mother died. He returned to Canada then rejoined his friend in Greece at the end of their planned two weeks together. His friend wanted to party that last night, but Ciceri was jetlagged and depressed about his mother’s death.

“He produced a little cocaine and I shared it with him. We enjoyed Athens that last night together but the next morning more than ever he got back into the ‘I hate Americans’ theme. We argued, our friendship dissolved, and we went our separate ways.

“Arriving back in Abu Dhabi the next day, the customs agent asked where I had been and after indicating Athens he said, ‘Ah yes’ in a tone that sent shivers up my spine. He knew to look for a black bag but quickly realized it wasn’t my black suitcase he wanted. Instead he told me to open my green backpack and he searched for my black toiletries bag.”

Eventually the agent found the glass vial that had held the cocaine — planted in his bag, Ciceri says, by his friend. “I was then arrested. It turned out to contain a 1/5000th ounce of cocaine but for even that I was charged with use, importation, and intent to distribute cocaine, something that could bring a sentence of four to 20 years.”

He was sentenced to four years and sent to Al Wathba, which Ciceri describes as “nothing but a crude punishment centre” in a desert between Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia.

“The blocks were Spartan,” Ciceri elaborates. “The rooms were empty concrete cells, no beds, no shelves. We were issued four blankets and two sets of prison garb. No television or radio. They wanted us to rot. Prisoners fought amongst themselves over everything — food, games, tribal enmity, views on religion.”

The food, he adds, was “typically miserable but twice a day we had tea that was better than the food. What I didn’t learn until well into my stay was that it was routinely spiked to inhibit our sex drive.”

Prisoners were routinely put in solitary confinement, he continues, hung by their wrists in front of other prisoners, flogged if they refused to attend Islamic lectures, and caned for being convicted of drug crimes. Thanks to efforts by the US Embassy, Ciceri was spared the caning.

His early days in confinement, Ciceri says, were like the movie Midnight Express. “It was disgustingly filthy and smelly… I felt danger all around me.

“I knew I had to make friends so I made a point of being friendly and open to conversation in our block and showed respect for everyone there. That wasn’t difficult, because I had developed a genuine respect for Arab people while working in the Middle East.”

There were other gay men at Al Wathba, Ciceri says. “Openly affectionate gay men were held in a cell in a common corridor where they could be taunted relentlessly. Others I got to know in my block kept a low profile. We would talk in rare moments when we had privacy. To be caught having sex with another man in the block could result in up to two years being added on to one’s sentence.”

Ciceri doesn’t think that the prison authorities ever discovered he was gay. “In my first visit with American embassy personnel I explained that I was gay and I feared for my safety. They assured me it would not be a problem and by being discrete it never was a problem for me,” he confides.

Leaders in the Middle East, notes Ciceri, much like a few high-profile religious bigots in the US, talk about the sickness of homosexuality, but they’re the ones you find soliciting sex in the gay bars and gyms.

What Ciceri experienced as a gay man while living and working in the Middle East was similar, he says, to the experience of gay men in North America 30 years ago. “Everything is clandestine. Finding a gay bar in the Middle East is an adventure, finding another gay person is exhilarating, and you felt ‘special.’ Younger gay people in our countries really can’t relate to that experience.”

Ciceri devotes a lot of time in his book to his faith, which he describes as the “rock that got me through all the misery and threats and chaos of prison life.”

“My religion is very personal and I don’t proselytize it,” he says. “When I went to prison I didn’t discover God like many do, but I took God there with me.”

A lifelong Lutheran, he belongs to a gay-friendly church in Key West. “I yearn for the day when there will be a separation of church and hate especially as it pertains to gay people. I know that God loves gay people no less than those who aren’t.”

As a Canadian, Ciceri is “impressed” by the advancement of gay rights here. “That makes me proud of my homeland,” he says. “The greater part of me still identifies as a Canadian and my partner and I have been talking about moving to Canada within a few years. Interestingly, the more I live in the United States the more I want to return to Canada. But Key West is a hard place to leave.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra