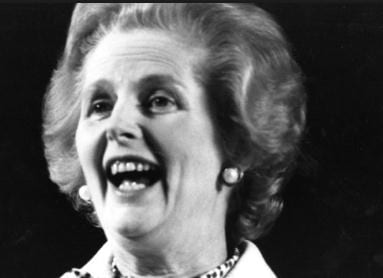

I moved to England in September 1987, three months too late to vote against Margaret Thatcher in a general election. When she was deposed in 1990, resigning on the advice of her close friends in cabinet after losing the confidence of the Conservative Party, I and some of my friends stood in front of the big iron gates of Downing Street, her official residence, and danced.

We were dancing to celebrate what we hoped was the end of an era: one in which her government had taken the safety net of the post-war welfare state, shredded it, and sold the pieces back to us. In Thatcher’s Fun House Britain, greed was good, there was no such thing as society, the solidarity of a trade union was evil unless it was Lech Walesa’s anti-Communist Solidarnosc, and the bossy, hectoring tone of a self-satisfied, cynical schoolmistress passed for female strength. Feminism was “poison,” families headed by lesbians and gay men could never be anything but “pretend,” and the poor were expected to pay the same share as the rich toward the cost of government services, with prison as the alternative for those who couldn’t or wouldn’t pay.

She took Britain into a war with Argentina, refused to apply sanctions to the apartheid regime in South Africa, befriended Augusto Pinochet of Chile, and called Nelson Mandela a terrorist. And she sneered at young people struggling with their sexual identity by claiming that schools must not tell children they have “an inalienable right to be gay.”

The Thatcher government’s policies adversely affected the lives of Britain’s lesbians and gay men in numerous ways, but perhaps the most significant was the passing of Section 28 of the Local Government Act. It made it illegal for any council to “intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality” or promote the teaching in any school of homosexuality as “a pretended family relationship.”

On April 8, 2013, Thatcher succumbed to a final stroke. Parliament’s tributes to her lasted seven and a half hours: the tributes to Winston Churchill after his death were dispatched in less than one hour. Her ceremonial funeral is expected to cost British taxpayers 10 million pounds, at a time when the government is calling for austerity and cutting social benefits further. The debate over her legacy has been loud and comprehensive, but the voices of gay activists have largely been unheard. I asked a random group of friends and colleagues from my time in Britain to contribute their assessment of her legacy. This is what they had to say.

**

“At the 1987 Conservative party conference, Margaret Thatcher used her big set-piece speech to mock “the inalienable right to be gay.” Under her leadership, the party used anti-gay election campaign posters and television broadcasts to try to win votes. In the general election that year, a speaker at an earlier Conservative conference told delegates to cheers that ‘if you want a queer for your neighbour, vote Labour.’ The Conservative leader of Staffordshire County council advocated tackling AIDS by gassing homosexuals; the police in numbers often 50-strong raided our pubs to check the alcohol licence was in order but failed, for example, to investigate an arson attack on the offices of Capital Gay. One of Margaret Thatcher’s MPs, Elaine Kellett-Bowman, approved in Parliament of the arson attack, saying ‘there should be an intolerance of evil.’ Two weeks later she was made a Dame on Margaret Thatcher’s recommendation. She . . . presided over a party and government that encouraged hatred of lesbians and gay men, and she used this hatred to gain electoral advantage. This is perhaps part of the reason that the late Derek Jarman referred to the long, dark night of Thatcher.”– Graham McKerrow, editor, Capital Gay, 1981-1989

“The Thatcher years in Britain involved an endless sequence of public protests on the part of all those who found themselves entirely excluded from the usual processes of everyday politics within civil society. Her style of conviction politics had no interest in political dialogue, so activism became for many the only possible mode of response. Of all the actions and demonstrations of those long years, I most fondly recall the OutRage Kiss-In at Piccadilly Circus on Sept 5, 1990, which so successfully drew attention to the general issue of ongoing police harassment of any type of display of queer affection in public. The boy who somehow clambered all the way up to the top of the famous statue of Eros to snog with the statue provided an enduring image of sexy public defiance to a whole climate of bigotry, the more moving when one recalls that this monument in the heart of London commemorates Lord Shaftesbury, one of the great heroes of the original campaign against slavery.” – Simon Watney, AIDS activist and art historian

“I was working for Lambeth Council in the publicity and marketing department. There was a big [anti-Poll Tax] riot throughout Brixton. When it was outside Lambeth Town Hall, I had my head out the window, yelling ‘Maggie, Maggie, Maggie, out, out out’ [a popular anti-Thatcher slogan, based on a soccer chant]. One of the press officers told on me, so I got sacked. But I was on full pay for three months, till my disciplinary hearing . . . I still say because she was a woman, she was vilified. For me, [Thatcher’s election] was a real change. Once, we had all our women’s centres and refuges and then she came and they went. There was a whole infrastructure of buildings that we lost, the places where we could meet and be safe.”– Vimalasara Mason John

“In the mid 1980s, all British gays were in a panic about this mysterious illness that only gays got. It had arrived from America, but Ronald Reagan denied there was any such thing. Margaret Thatcher, in turn, denied that this non-existent disease had arrived in this country. The only info to be had was printed in the gay press and gay sex mags . . . at that time there was a serious porn clampdown. The ‘Indecent Display (Control Act),’ meant that sex shops were getting regularly swooped. Porn, and what was thought to be porn, was confiscated and all that valuable safer-sex education taken along with it. The Health Education Authority found it really tricky to put the facts across of a virulent sexually transmitted illness without breaking any of the indecency guidelines. After a few dreary adverts that said virtually nothing, they asked me to do an explicit safer-sex booklet but in cartoon form, thinking that might do the trick. It was to be distributed in gay clubs and saunas so there was little risk of it getting into the wrong hands. I drew and wrote this booklet . . . I included everything I could think of, using the word ‘fucking’ with images that told the story in a jokey way that couldn’t really have offended too many people . . . When it was printed, I saw my drawing had been replaced, changed to a naked man (no bits showing) sitting on the back of a handsome centaur and the word ‘fucking’ changed to ‘Riding the Passion.’ To my knowledge, not one centaur has ever died of an HIV-related illness . . . so . . . a campaign that was a total success. – David Shenton, artist

“I won’t be mourning for Thatcher. Section 28 was a pernicious piece of legislation, brought in by Thatcher’s government, which told lesbians and gay men that we were second-class citizens, that our family relationships were ‘pretend’ and that children needed to be shielded from consideration of our lives. I wonder, did she ever consider the impact that legislation would have on a young person, struggling to come to terms with their sexuality? When lesbian or gay teenagers took their own lives, did she admit that their blood was on her hands?” –Matthew Hodson, CEO of the UK gay men’s health charity GMFA

“I’ve been gobsmacked in the past few days to find myself arguing on Facebook with young gay men who were barely born when Margaret Thatcher left office and think she was some kind of gay rights pioneer. This seems to be the result of woeful reporting by the website Pink News, which described her as “a controversial figure on gay issues” – a bit like saying Hitler was a controversial figure on Jewish issues – and even referred to her as a gay icon. Some people are also confused about Section 28 . . . The backlash against it gave birth to the modern gay-rights movement, which has morphed into the crazy idea that we ought to be grateful to her. And I think there’s a Streep factor: if Meryl played her, what’s not to like? In reality, the Thatcher government went all out to vilify anyone who dared defend the gay community in its darkest hour in the ’80s, saying our friends must either be perverts or loonies. That was what Section 28 was all about, and that will be her legacy for the great majority of gay people who lived through that era.” –Simon Edge, journalist

“Not only were we fighting for our sexual politics, not only were we fighting for the right to have sex the way we wanted, we were also fighting against our own communities. It was a fantastic, scary time, but I also remember the depression. In the early ’80s, when Thatcher’s policies were starting to affect people financially, it felt so hopeless at times. Part of what felt oppressive was feeling that we were so silenced because of Clause 28. Nothing positive could be said of us. We were so far outside of society. That could be why SM took hold. ‘You think we’re perverts? We’ll show you fucking perverts!’ From the early ’80s to the mid-’80s, the country felt depressed and hopeless. It felt grey. By the late ’80s, through political action, marches, trying to do something, we went from depressed to being angry. Being angry is a much healthier place to be.” –Del LaGrace Volcano, photographer

“I was living in the Middle East during the 1980s but visiting London frequently. Because of the battle over Thatcher’s foul Section 28 — news of which was being followed around the world – I decided to time my next visit so that I could attend the big London Pride in 1988. There, for the first time, Ian McKellen – the famous and charming actor – spoke as an out gay, starting a cascade of well-known folks coming out publicly as a protest against Section 28. I don’t remember the words he spoke, but I remember the electricity in the huge, defiant crowd and the sense that McKellen’s example of total commitment was going to tip the balance.” – Sue Katz, author, blogger, journalist, suekatz.com

“There are a number of things I remember. The night she resigned, we went to Downing Street and were surprised by how few people were there. It was as if she was already a forgotten woman, yesterday’s politician. So many memories because I was 21 in 1979, my first vote, and she defined the politics of my generation. It wasn’t just the miners who were the enemy within: we all were, and proud of it.”- Linda Semple

“While Margaret Thatcher was PM, I was working as a designer, first on Gay News, then Gay Times. Part of my job involved ploughing every month through a large brown envelope packed with cuttings supplied by a clippings service, to pick out illustrative material for the review of gay-related issues in the press. That’s the filter through which I experienced her years of power. It’s shocking now, to look back at the violent animosity of those headlines and editorials. I remember the last straw coming as the Daily Star, a major offender, casually dismissed the Terrence Higgins Trust as an organization named after ‘the first British queer to die from Aids,’ at a time long before the word queer had been proudly reclaimed and still carried a calculated emotional force. Letters to editors were useless at a time when tabloids were engaged in a dick-swinging competition to see who dared cause maximum offence to poofs and lefties. I was part of a small band who toddled down to Fleet Street, then home of the UK national press, and daubed pink triangles over the Daily Express building (out of which the Star operated). With hindsight, it was only a piddling gesture, but we wanted to send a message that we were out in the world and we were angry. The defining spirit of the Thatcher era was an appeal to the worst in the British character: selfish, mean-spirited, spiteful and utterly devoid of empathy.” –Tony Reeves, film critic

“The Thatcher years were very dark times for gay men and lesbians in the UK. It was hard not to internalize all the hatred and fear, which emanated from the newspapers, TV and radio and from the rabid blue-rinsed dames, the lords and MPs from the Tory shires. God knows what we might have done if ecstasy hadn’t come along to help us forget the pain in the glorious wee small hours of Saturday night, Sunday morning. Clause 28, as originally proposed and conceived, would have decimated the very limited gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender community that we thought we could rely on. If the local councils – which did, and still do, have wide-ranging administrative powers to support and licence social spaces and health and welfare organizations – had really been prevented from ‘promoting homosexuality,’ we would have lost our lives. No more pubs and clubs, no more helplines, no more drop-in centres. No more library books. No more information leaflets. No counselling. No healthcare. No nothing. That is what I really feared was the intention of all the hatred. Nothing less than a sort of homophobic carpet-bombing. I can only thank god that so many thousands did rise to the challenge. Took up their pens and took to the streets. And abseiled in the depths of hell [the floor of the House of Lords] to fight the viciousness of the dogs of hatred that Thatcher unleashed.” – David Smith, former editor of Gay Times

“5:10pm, Nov 22,1990, homeward on the Central line, pulling out of Chancery Lane, when the driver’s voice interrupted a mundane journey — ‘Ladies and Gentleman, I’d like to announce that Margaret Thatcher has resigned!’ — words greeted with an uproarious cheer and, uncommonly, followed by conversation among the passengers. A fond memory.” – Megan Radclyffe, television critic

“The most moving event I attended was the benefit for Rose Marie at Traffic in York Way. Rose Marie was probably the worst drag queen ever. He was a small, gentle Irish man with very thick pebble glasses. Improbably, he worked a navvy by day, but by night he would put on his ill-fitting frock, his terrible wig and his badly applied makeup and would stand up and mime to ‘Bobby’s Girl’ (‘I wanna be Bobby’s girl,I wanna be Bobby’s girl’). I say ‘mime,’ but Rose Marie’s gestures were invariably completely out of sync with the song. Amazingly, Rose Marie had a professional career as a drag queen. I must have seen him 20 or 30 times, always the same, always grotesquely bad. But everyone loved him, I think because of his courage and his determination and his complete absence of fear. One night Rose Marie picked up a man and was savagely beaten to death. It was shocking but not uncommon in those times as the index of violent attacks and murders of gay men rocketed under Thatcher. All the drag queens of London got together and decided to hold a benefit for Rose Marie at Traffic, a sleazy dive in Kings Cross. Every drag queen in London was there and every drag queen performed as if their life depended on it. It went on until about 4am. Divine was there and trod on my foot in her stilettos, which was very painful! It wasn’t political with a capital ‘P.’ It was love and admiration and respect and a demonstration that whatever the world threw at us, the show would go on. Very moving, very dignified and truly noble.” – Neil McKenna, author of Fanny and Stella: The Young Men Who Shocked Victorian England (Faber & Faber, 2013)

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra