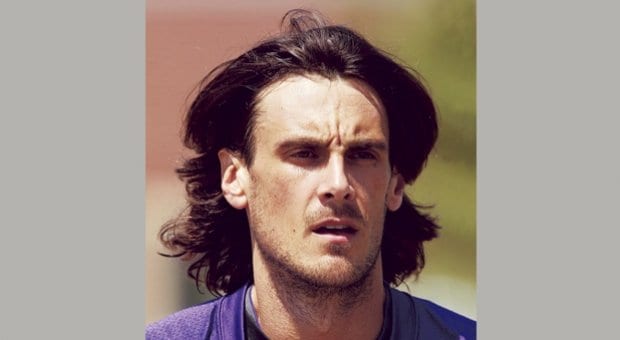

As a gay man, retired NFL player and now the executive director of the You Can Play campaign, Wade Davis doesn’t want to believe that Chris Kluwe was fired for his gay-rights advocacy. Credit: Courtesy of Wade Davis

When Chris Kluwe agreed to speak out for gay rights in 2012, he never expected that it would cost him his million-dollar career on the field.

Kluwe was a punter for the Minnesota Vikings in the National Football League, arguably the best punter the Vikings had ever had. His last year on the field, he averaged 39.7 net yards per punt, the highest of his consistently solid career.

It wasn’t enough to keep his job.

In a Deadspin article that reverberated through the sports world in early January, Kluwe alleges that he was fired by “two cowards and a bigot” — the cowards being Vikings general manager Rick Spielman and now-fired head coach Leslie Frazier (who was axed himself Dec 30 after a disappointing season). Kluwe reserves the bigot status for special-teams coordinator Mike Priefer.

Though he can’t say for sure, Kluwe says he’s “pretty confident” that his gay-rights activism got him fired.

“My [punting] numbers were still exactly the same, and I’d been doing everything that the coaches wanted me to do and no one had ever expressed dissatisfaction with how I was performing, so I look at everything and I — the thing that changed is I started speaking up,” Kluwe tells Xtra by phone Jan 9.

Kluwe began speaking up during the summer of 2012, when he was approached by a group called Minnesotans for Marriage Equality as a constitutional amendment to limit marriage to one man and one woman made its way toward the ballot box. (The amendment would be defeated, making Minnesota one of four states to support gay marriage in the November 2012 referenda, along with Maine, Maryland and Washington.)

By November, tension had escalated not only on the election front, but behind the Vikings bench, Kluwe alleges.

At the season’s outset, Kluwe says, he sought and obtained permission from the team’s legal department to publicly support gay marriage. A few weeks later, he published an open letter responding to Maryland delegate Emmett C Burns Jr, who had pressured the NFL’s other outspoken gay rights advocate, Baltimore Ravens linebacker Brendon Ayanbadejo, to stop speaking out.

Burns’s letter, written on Maryland House of Delegates letterhead, leaned on Ravens owner Steve Bisciotti to “take the necessary action” to “inhibit such expressions from your employee.”

Kluwe was shocked. “I find it inconceivable that you are an elected official of Maryland’s state government,” he wrote to Burns in a letter that quickly went viral. “Your vitriolic hatred and bigotry make me ashamed and disgusted to think that you are in any way responsible for shaping policy at any level.”

Suddenly thrust into a spotlight of gay-rights support, Kluwe’s coaches seemed less than comfortable.

Kluwe says Frazier called him into his office to ask him to tone it down. When he refused, Kluwe alleges, Priefer, the assistant coach in charge of special teams, including the punting crew, and Kluwe’s direct supervisor, grew increasingly hostile, asking him, among other things, if he’d written any more letters defending “the gays” and denouncing the idea of two men kissing.

Kluwe claims Priefer’s antagonism culminated in a special-teams meeting in November 2012 where he declared, “We should round up all the gays, send them to an island, and then nuke it until it glows.”

Priefer denies the allegations and, in a public statement, says he does not tolerate discrimination of any kind. “I personally have gay family members who I love and support just as I do any family member,” he adds.

The Vikings also deny the allegations and, in their own public statement released Jan 2, promise to “thoroughly review this matter.”

“As an organization, the Vikings consistently strive to create a supportive, respectful and accepting environment for all of our players, coaches and front office personnel. We do not tolerate discrimination at any level,” the statement says, adding that the team would not have impinged Kluwe’s free speech.

“Any notion that Chris was released from our football team due to his stance on marriage equality is entirely inaccurate and inconsistent with team policy. Chris was released strictly based on his football performance,” the statement says.

Vikings public relations staff refused to comment further and referred Xtra back to the statement.

It’s hard to prove causality in cases of discrimination-based firing, Kluwe tells Xtra. “I mean, it’s always going to be hard to prove because unless you can read someone’s mind, you can’t say with certainty what their intent was.”

Asked what other factors could have contributed to his firing, Kluwe openly examines the possibilities.

There’s his age, he quickly points out. At 32, he’s not getting any younger, though he’s equally quick to point out that punters tend to have more longevity on the football field, and he knows of several his age who recently signed contracts.

His performance hasn’t deteriorated, he continues. If anything, he had his strongest statistics in 2012 (the year he was so outspoken). He continues to punt well — “45 yards outside the numbers with hang time, and in the NFL that’s supposed to keep your job as a punter at least until you’re 38 or 39,” he says.

Admittedly, his consistently solid numbers were only “middle-of-the-pack, sometimes a little lower” when ranked against all NFL punters. Though it’s also worth noting that the pack, in this case, consists of the best football players in the world, and his replacement on the Vikings roster kicked somewhat shorter than he did in net average yards this season.

Kluwe also claims that Priefer repeatedly asked him to kick shorter punts to give his teammates a better chance of getting downfield in time to prevent their opponents’ run-backs. Not an unreasonable request from a special-teams coach and one that Kluwe says he gladly took for the team. But it affected his numbers, he says.

Then there’s the money question: Kluwe had one year left on his five-year, $8.3 million contract, making him one of the highest-paid punters in the league.

But, he says, the Vikings never approached him with a request to decrease his salary. “They never talked to me about money being an issue at all.

“And I was actually cheaper than other punters that came in at a similar time as I did and had similar numbers,” he adds.

Asked if he was looking for a career change and wanted to go out with a bang, Kluwe laughs. “No, no. I was actually looking for a contract extension! I’d been talking to my agent about talking to the Vikings,” he says, adding that he had been hoping to play with the team for another four to five years.

Everything seemed fine, he reiterates — until he started speaking out for gay rights.

“My punting stats were very consistent year to year, and, like I said, no one had ever expressed dissatisfaction with the job that I was doing,” he says. “What’s the one thing that changed? I started speaking out on same-sex marriage rights.”

***

Wade Davis doesn’t want to believe that homophobia cut short Kluwe’s career in the NFL.

The retired NFL player, and new executive director of the You Can Play campaign to challenge homophobia in sports and make fields and rinks more welcoming to gay players, is struggling with this story.

“This is the most complicated story that I’ve ever had to speak about,” he says candidly. “The hardest thing about this story is that either you’re going to bash the NFL or you’re going to bash Chris. For someone who is a gay man and an ex-NFL player, I’m like, ‘Oh my god, how do I speak about this and be respectful of two entities that I believe in?’”

Davis didn’t come out until two years after he left the NFL, but he doesn’t blame the league. “I had so much self-hatred and internalized homophobia that I had to really work through,” he says. The NFL didn’t keep him in the closet, he says; he was already there.

These days, his life is considerably different. He’s been out to family and friends for eight years and publicly out for two. He works with gay youth and last year took the helm of the campaign launched by hockey’s Burke family and friends in 2012 to change the culture of sport.

But he’s reluctant to conclude that the NFL as a whole is homophobic. “Let’s not single-story the NFL,” he says. “Let’s not tell an incomplete narrative.”

Though he thinks there’s “still a lot of work to be done around homophobia in sports,” he also says football is like any other industry: there will be individuals who are homophobic, but that doesn’t define the league’s culture overall. “I’m not painting a picture of kumbaya and roses,” he says, “but I do believe that players are a lot more accepting than we give them credit for.”

Kluwe, too, says his teammates were generally supportive. Even the players who disagreed with him expressed their opinions respectfully, he says.

It’s not a question of pervasive, institutionalized homophobia throughout the NFL, he agrees, adding that Vikings owner Zygi Wilf was also supportive and even shook his hand and encouraged him to keep speaking out.

It’s his coaches’ bigotry and cowardice that got him fired, Kluwe alleges.

Davis has a hard time with that, too. “I do believe that what Chris said happened, happened,” he says, “but I can’t just point to that as the reason he was let go.”

“The NFL is a what-have-you-done-for-me-lately league,” Davis says, asked to provide an alternate explanation for Kluwe’s termination. “If you aren’t at the top of your game 24/7, you could be cut.”

“Chris wasn’t a top-10 punter,” he notes. “If Chris was a top-10 punter, I really doubt that we’d be having this conversation.”

If the Vikings could find a younger player to punt with the same success rate for less money, that would be a financial decision, he says, and the NFL is a business.

Plus, the NFL doesn’t like distraction, he continues. If coaches perceive a player to be a distraction, and his productivity doesn’t justify the distraction, then he’d be in danger of getting cut. The coaches might begin to ask themselves, “Can we find someone cheaper to do this kind of work?”

“I think distraction is a euphemism for non-corporate behaviour,” Kluwe contends. Front office and administrative types get concerned about players speaking out on contentious subjects because if fans object, it could cost the team profits, he says.

Kluwe wonders how big a distraction he could have been to his teammates since, after a disappointing season in 2011, they unexpectedly made the playoffs in 2012, the year he was so outspoken.

Still, Kluwe concedes that “the distraction word” probably kept him from getting a spot on another roster after the Vikings released him. “I think other teams look at it and they’re like, ‘This is the guy who is willing to speak out on things, and if that’s the case, then we’re going to pick a different guy.’”

Kluwe tried out last spring for Chicago, Buffalo and Cincinnati but got no bites. He was briefly signed to the Oakland Raiders, but the team cut him in favour of an up-and-coming star punter, he says.

Davis says the Raiders’ willingness to sign Kluwe and give him a chance shows at least one NFL team wasn’t put off by his advocacy.

It would be easy to conclude that the Vikings cut Kluwe for his advocacy, Davis says, but it may not be accurate. “I can’t be sure if that’s true or not. I would hope that it’s not true.

“I want to believe that he wasn’t let go because of his LGBT activism.”

Whether Kluwe’s allegations prove true or not, Davis says his courage to speak out should be honoured. “The work that Chris has done has been bold and courageous,” he says. “Any time someone tells their truth, it changes the world for better.

“If what Chris said is true, then I believe that the Vikings organization and the NFL will come down hard on the people who were involved and make sure that it doesn’t happen again,” he adds.

***

Despite the potential consequences, Kluwe says he doesn’t regret speaking out.

“If the positions were reversed and I needed someone to speak out for me if I was in trouble, and they could potentially lose their jobs, then I’d want them to do so,” he says.

“I mean, it’s just a game. I think basic human rights are probably a little more important than playing a children’s game, when all is said and done.”

Asked if he’s concerned that other straight allies might be discouraged from speaking out now, given the way things ended for him with the Vikings, Kluwe says they should know that with activism comes potential consequences.

“If you’re not willing to risk what you have, then your heart’s probably not in it,” he says.

“What kind of world do we want to live in?” he asks. “Is it one where we are free to speak out on important social issues? Or is it one where everyone is tiptoeing around things and worried about saying anything at all because they’re worried about losing their job?”

Davis says it’s essential that straight allies keep speaking out. “They create space for LGBT individuals to speak out for themselves,” he says. “I think that’s what someone like Chris is doing: he’s stepping up, he’s showing bold and courageous leadership.

“His career is over. There’s very little chance that Chris will ever play again. But that speaks to what the movement needs — someone to be that bold and that courageous.”

Stripped of his punting duties, Kluwe doesn’t know what he’ll do next. “I’ll probably keep writing,” he says. “I find that I enjoyed it. Watch my kids grow up. And just see what life throws at me.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra