“Ms. Platek, can you help me?”

As a teacher, I hear this question at least 100 times a day. But as a closeted, non-binary teacher, hearing the title of “Ms.” 100 times a day can be exhausting. Such was the reality during my first student-teacher placement—in a rural Ohio school where LGBTQ2S+ identities are seldom acknowledged.

When I decided in 2017 that I wanted to become a teacher, I knew that it was about more than just my passion for the content and curriculum. It was about creating a safe space for LGBTQ2S+ students—the environment I never had and dearly wished for growing up. I attended Catholic schools in Cleveland, Ohio. Despite having friends and a relatively easy high-school experience, I hid my sexuality. Between silently fearing reactions from family and peers, hearing rumours that lesbians were kicked out of school and thinking that I would “burn in hell,” it’s not too surprising that I tried to “pray the gay away” as often as I could.

After joining my school’s youth group, I reached out to a priest about my dilemma. He told me that even intrusive thoughts, whether or not they were acted upon, reflected who we are and were sinful; they needed to be purged from my soul so that I could be clean and whole. It wasn’t until I graduated high school in 2015, when gay marriage was legalized across the United States, that I heard positive talk about the queer community. That same year, I went to college, eventually found my voice and began taking pride in who I am.

I knew that I wanted to be an out-and-proud queer teacher and a role model for LGBTQ2S+ and questioning kids. I know how hard those pivotal adolescent years can be for queer and trans youth who are figuring out their identities while simultaneously being demonized by members of their home state.

Ohio also has a legacy of not only mistreating adult members of the LGBTQ2S+ community, but kids. In 2018, state legislators tried to pass House Bill 658, which would force teachers to out trans children to their parents. At the beginning of 2020, another bill was introduced in Ohio that would make it illegal for trans children to receive gender-affirming health care; it would also punish the doctors who try to help them. More recently, two transphobic bills were introduced in the Ohio Senate and House that directly attack transgender youth. Misleadingly named the “Save Women’s Sports Act,” Senate Bill 132 and House Bill 61 would prohibit trans children from engaging in sports that align with their gender identity. Despite being unable to produce a single example of transgender children “harming” cisgender children’s ability or chances to compete in the same sport, more than 20 states have introduced a similar version of this bill.

“Instead of being the trailblazer that I had always envisioned, I was repeating my own closeted eighth grade experience.”

What I didn’t know while watching these transphobic debates unfold in my home state was that I would be doing my student teaching at a rural Ohio school in the midst of Trump country—a placement my student teaching program randomly selected for me. Nor did I anticipate I’d come out as non-binary to myself during my time there. Suddenly, I was sent spiralling back into the closet, too nervous about announcing my name and pronoun changes at a school where I was a guest and had no real protection. During the 2019-20 school year, when I was in training, Ohio did not have any statewide laws about LGBTQ2S+ discrimination; members of the queer community could face prejudice in employment, housing and other public accommodations without any legal repercussions. Instead of being the trailblazer that I had always envisioned, I was repeating my own closeted eighth grade experience.

There were progressive pockets of the school: It boasted a Gender and Sexuality Alliance (GSA) and some teachers displayed posters about diversity and inclusion. But the stigma still lingered. Some teachers had Blue Lives Matter flags hanging in their classrooms; others openly scoffed at the idea of having to use the pronouns that their students asked them to use. I didn’t feel comfortable sharing the fact that I had a girlfriend to the majority of the staff, and it wasn’t until a couple months passed that I shared this fact with only the teachers who I felt most comfortable with. Some parents seemed less than thrilled to meet me during parent-teacher conferences; I distinctly remember one of them giving me the stink eye. That parent made it a point to let me know that their child was going through “a difficult phase,” but that they were “working through it together.” While eyeing my short hair and queer outfits, she had seemingly forgotten that her child had identified this way long before I showed up to the school. Thankfully, my mentor teacher and the other eighth grade teachers were very welcoming and supportive, even if they didn’t know about my own identity struggles.

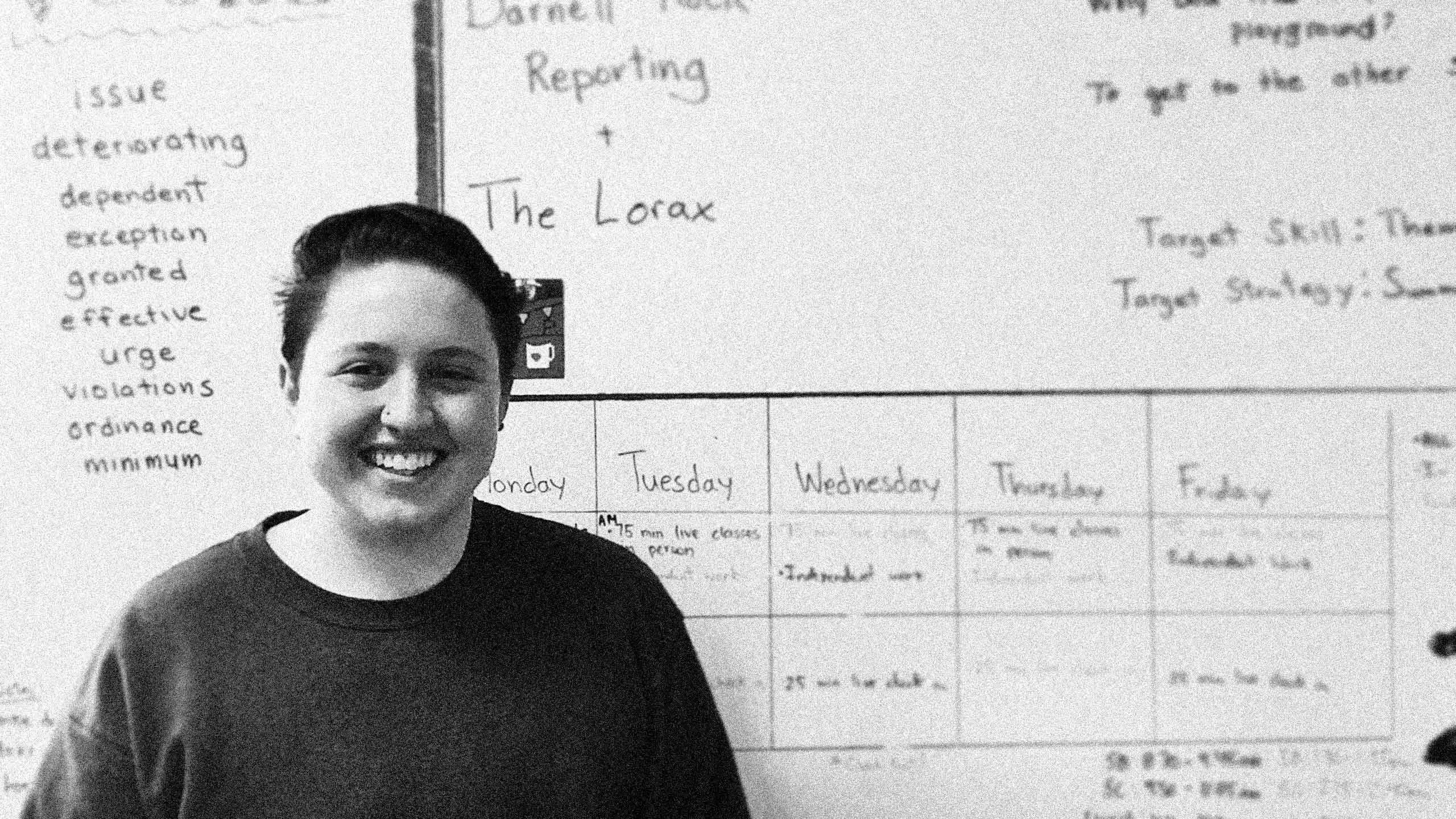

Credit: Courtesy Gill Platek

Much to my surprise, it was my students who displayed their resilience and created their own safe space with me. Each morning they would come to see me while I was in the hallway welcoming students into school. It became almost like a club; the first 10 minutes of the day were filled with our conversations. While I never did come out as trans or non-binary during my time at that school, that didn’t stop the queer eighth graders I had in class from turning to me. These students were able to recognize themselves in me during the seven months I was in their classroom. They talked to me about their friendships, their problems with being closeted and what pronouns they wanted me to call them in private. They confided in me about the homophobia and transphobia they experienced throughout the school year—whether it was prejudiced roommate conflicts during their Washington, D.C., trip, or parents who thought they were “confused.” They felt safe enough to confide in me about these experiences, and I gave them the support and advice that they needed to hear. I was their safe space and they were mine—even though none of us were out to others.

I often find myself wondering how those kids are doing now that I am not there. I can only hope that they found someone at their high school who is looking out for them and can provide them with a new safe space where they can feel at home to be their true selves. Despite my hopeful wishes, I know that many of those students are likely still struggling with their identities and how they exist in a place like Ohio. While they may find pockets of safety and acceptance, I know all too well that they are far and few between. School should be a safe place for all kids, no matter their sexual orientation or gender identity. This should not depend on the area that the school resides in; students in conservative areas should not have to suffer.

Sometimes, we aren’t able to come out or create the safe spaces that we deserve because the law doesn’t protect us or the social stigma is debilitating. But after meeting those students and realizing that they deserve better, I made a promise to myself: Once I graduated with my teaching degree, I would only apply to jobs that would accept me as a queer, non-binary teacher. I put my new name and my pronouns at the top of my resume, even if it meant I might be automatically rejected from certain schools.

In 2020, I had the privilege of finding work at a school on the south side of Chicago, teaching reading to fifth graders. Now, I am among a supportive school community where everyone strives to use my correct pronouns and has no problem calling me Teacher Platek.

“I made a promise to myself: Once I graduated with my teaching degree, I would only apply to jobs that would accept me as a queer, non-binary teacher.”

Still, I can’t help but think about all of the LGBTQ2S+ kids in my home state who I had to leave behind, and students in other conservative areas who have no one in their corner looking out for them. I know Ohio is not an anomaly when it comes to legislation regarding LGBTQ2S+ youth—several states across the country are actively trying to ban trans students from participating in sports and bar trans youth from accessing gender-affirming health care. Among them is Florida, which made headlines for the proposed “genital inspections”’ that would be permitted for athletes whose gender is brought into question. A bill in North Carolina would prohibit trans people under the age of 21 from receiving gender-affirming surgery and force state employees to tell parents about any displays of “gender noncomformity.” And Iowa’s “Bathroom Bill” would prevent trans students from using the restroom that matches their gender identity at school.

While I had to do what was best for me and my own well-being, there isn’t a day that goes by where I don’t wish there was more I could do to support kids in unsupportive areas. One day I hope to return to Ohio, protected by the law. I want to act as an example and support system for kids who may have otherwise felt alone—because no one deserves to feel that way.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra