Four and a half years ago, Shawn Ewing and her wife left their apartment in Vancouver’s West End to move to the suburbs. For the Ewings, leaving the gaybourhood for Surrey was a question of simple math.

“Two thousand square feet and a yard versus a little under 700 feet in an apartment,” she says. “Accessibility to the party downtown wasn’t important to us anymore. What was important was a house and having a yard and a garden and all of that good stuff.”

Ewing, a former president of the Vancouver Pride Society, is now vice-president of Surrey’s Pride organization. She says that despite Surrey’s conservative reputation and some early fears that they might have to “straighten up,” her family has had no problems at all.

“We haven’t changed any of our behaviour,” she says. “I don’t have a problem holding my wife’s hand when we’re walking down the street or giving her a kiss in my front yard.”

“I probably got called out more living downtown about being a dyke than I certainly have been in Surrey,” she says.

From Vancouver’s Davie Village to Toronto’s Church Street to Montreal’s Le Village, everyone has their own opinion about Canada’s gay neighbourhoods, but few seem to disagree that they are in decline.

Whichever name you call it — the gaybourhood, gayvenue, gay district, gay mecca, gay ghetto — the question of its future isn’t limited to Canada. Across the border in the United States, many notable gay districts are also fading into shadows of their former selves, from San Francisco’s Castro to Chicago’s Boystown to Seattle’s Capitol Hill to countless more.

In his recently released book There Goes the Gayborhood?, Amin Ghaziani, an associate professor of sociology at the University of British Columbia, examines the changing face of the gay neighbourhood. His research is based on census data, opinion polls, more than 600 newspaper articles and more than 100 interviews with gaybourhood residents.

“I myself lived in Chicago’s Boystown district for nearly a decade, starting in 1999. I remember feeling uneasy in those years as I read one headline after another about the alleged demise of my home and other gayborhoods across the country. The sight of more straight bodies on the streets became a daily topic of conversation among my friends — an obsession to be honest,” Ghaziani writes.

“As the years went by, my friends and I bemoaned, perhaps most of all, feeling a little less safe holding hands with our partners, dates, or hookups — even as we walked down what were supposed to be our sheltered streets. I had been called a ‘fag’ on more occasions than I still care to remember, and I was shocked at the disapproving looks that I would receive when walking hand in hand with another man. I knew I could not escape this menacing straight gaze altogether, but I was so angry that I had to deal with it in Boystown. This was supposed to be a safe place,” he writes.

According to statistics, the days where the gay community was drawn to live and work in a single neighbourhood are ending. American census data shows that same-sex-couple households have become “less segregated and less spatially isolated across the United States from 2000 to 2010,” Ghaziani writes. “This is a restlessness that clearly appears in cities across North America. To wonder where gayborhoods are going, debate whether they are worth saving, or question their cultural resonance — all of this announces to us that they are in danger.”

Although gay bars have been around since the start of the 1900s, gaybourhoods are a fairly recent phenomenon. It wasn’t until after the Second World War that they really began to flourish in North America, buoyed first by the thousands of men and women dishonourably discharged from the military for their presumed homosexuality and later by migrating single gay men and lesbians from smaller towns in search of a place to call home. Gaybourhoods promised safety and freedom, as well as places to find love and sex.

Ghaziani points to several factors that are changing these areas today: the increased acceptance of gay men and lesbians by society and under the law, allowing many people to feel safer moving to more spacious accommodations in the suburbs; growing development and gentrification, leading to rising property value and rents, driving some people out of downtown areas; and the increased migration of straight people back into desirable urban areas.

Ron Dutton has lived in Vancouver’s West End for 40 years and has never once wanted to leave. “I like the diversity of people, the sense of openness,” he says. In his opinion, changes are constant, and except for the rapidly increasing cost of living, he doesn’t think the changes are negative.

“Individual businesses come and go, but I don’t see the neighbourhood becoming any less welcoming,” he says. Still, Dutton laments that many seniors on fixed incomes have been leaving the area against their will as rents continue to skyrocket.

As some gay people resist the tide and stay in gay neighbourhoods, many more are undeniably leaving — even as North American cities begin to recognize their cultural and, especially, potential financial value.

The permanent rainbow crosswalks in Vancouver and now in Toronto and the newly installed rainbow LED strip lights in Vancouver are all being used to promote these villages as destinations, to locals and tourists alike. These efforts at urban renewal can also contribute to the gentrification that eventually prices many gays and lesbians out of these areas.

To many, especially to the younger generation, the notion of a single gay district seems antiquated. As gay people, men especially, increasingly turn online to find sexual and romantic connections, their need for gay bars and physical places to meet and hook up diminishes. As the world becomes safer for some sexual minorities, the need for the protective embrace of the gaybourhood also begins to decline. In the early 1990s, there were 16 gay bars in Boston. By 2007, that number had dropped by half.

Ghaziani references these phenomena as part of the “post-gay” era, where gays are being accepted by society and are choosing to assimilate into the mainstream. He says it’s changed the way many of us think about ourselves.

As an example, he points to statistician Nate Silver, who was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in 2009. In a 2012 interview with Out magazine, Silver said that his friends saw him as “sexually gay, but ethnically straight.”

Ghaziani’s book defines “post-gay” partly as an assertion that who a man has sex with “is not necessarily related to his self-identity or to the cultural communities in which he participates.” He compares this sort of sexual identity with white ethnic identity: “optional, episodic and situational.”

In reviewing media interviews with various gay people — often couples — who have chosen not to live in gaybourhoods and who say they are fitting in, he notes that their tones are often laced with some shame. He wonders why the opposite of “blending in” is having a “scarlet letter on our heads” or being “those people?”

“Assimilation into the mainstream is always accompanied by infighting within a minority group, especially between those who are eager to blend in and those who are determined to hold on to what makes them different,” he writes.

Interestingly, Ghaziani’s book also includes interviews from some of the straight people living in gaybourhoods. He finds that many are “benignly indifferent” to their gay neighbours, while a minority feel that they are victims of reverse discrimination.

He found the responses of straight people so repetitive and almost rehearsed that it was hard to tell if they were being honest about being indifferent or if they were just being politically correct. One single, straight 28-year-old in Boystown told Ghaziani that he would like to see the rainbow pylons and flags taken down because, in his opinion, self-segregation was hurting the gay movement politically.

Ghaziani argues that even while many outgrow them, gaybourhoods remain “culturally relevant as refuges for queer youth of colour, transgender individuals and queers who hail from small towns, because antigay bigotry still affects their everyday life.”

Despite having left the confines of Vancouver’s gay village, Ewing agrees that there will always be a need for the gaybourhood, but she stresses the importance of it needing to be about more than just bars. She would like to see more places that include non-drinkers and youth.

Ghaziani suggests that it’s unreasonable to expect gaybourhoods — or any neighbourhood, for that matter — to remain stable and unchanged but that it’s equally unreasonable to declare them dead.

Neighbourhoods often move, reform and migrate, he says. Toronto’s “Queer West” and Vancouver’s Commercial Drive are two such examples. Many young queer people may want to live in a gay area, but they settle where they can afford the rents, even if that means congregating in — and queering — new neighbourhoods.

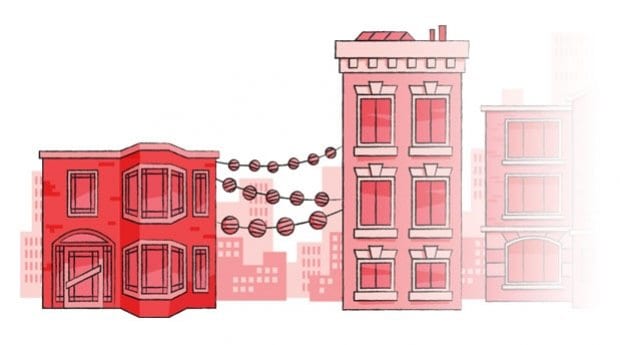

Ghaziani further theorizes that these gay-friendly neighbourhoods could eventually become full-fledged gay neighbourhoods in their own right. If the old gaybourhood was an island, these new models are archipelagos. These new villages may eventually supersede the older ones, or they may all coexist.

Dutton says that while we have gained a lot of freedom under the law, that doesn’t negate the need for the gaybourhood. “I think there is much to be said for an accepting environment where people can feel free to dress unusually or where they can express their affection for one another openly. That would be regretful if those things were lost over time,” he says.

“I don’t think the times have progressed to the point where we’re all just equal,” he continues. “There is much to be said for having a place within the city where people can come from elsewhere and feel that this is home — this is where my people congregate.”

There Goes the Gayborhood?

Amin Ghaziani

Princeton University Press

press.princeton.edu

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra