In January 2020, South Korea was one of the first countries to confirm cases of COVID-19 among its residents. Two months later, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. That’s when fear and hate began to spread against those ill with the virus, patients and victims. Some of those targeted unfairly received much more hate than others—particularly us in the gay community.

As a queer activist, artist and blogger, I watched this unfold firsthand. In May, owners of one of the big gay clubs in Itaewon—in an area called Homo Hill—wrote a post on their Facebook page saying that their club had been exposed to COVID-19. They said they would act responsibly and do their best to help stop the spread of the virus while co-operating with the government. The news quickly went viral within the LGBTQ+ community in South Korea. Blame and witch-hunting soon followed.

Within the next day, Korean news sites and search engines plastered the words “gay,” “gay club,” “homosexuality” and “homosexual” alongside “coronavirus.” Journalists led with provocative headlines that suggested COVID-19 was linked to gay people. And the text messages sent out to every individual in the country from the government included the names of the clubs on Homo Hill—the few (until then) uninvaded places where we could feel safe and be our true selves.

On the same weekend as the outbreak on Homo Hill, clubgoers carrying the virus attended another non-gay venue in Itaewon. The venue’s staff members later travelled to a club in Gangnam, which resulted in further spreading of the virus. But the media was too busy focusing on gay people—we were easier targets.

The clubs and bars on Homo Hill that were exposed to the virus provided lists of people who visited them and their contact information to the government. The government had no proper guidelines or systems in place to protect COVID-19 patients’ personal information, so when someone turned out to have the virus, they instantly became the target of hate coming from their neighbours and acquaintances—and the rest of the country. In fear of their privacy and safety, many people on these lists did not answer the government’s calls; some didn’t even receive the calls, having provided fake names and contact info at the club to protect their identities.

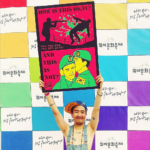

Credit: Courtesy Heezy Yang

For LGBTQ+ Koreans, the events triggered a sense of solidarity—we knew we needed to fight back.

When I spoke to some of the owners of the bars on Homo Hill, they told me that they were treated “differently” than other bars and couldn’t open even after the venues were disinfected, though other bars were allowed to. One bar owner said he provided CCTV footage to the government that shows the inside of his bar and his customers so that officials could try to trace people who were in the area on the night of the outbreak; he later found out that the footage was used in a television program. On the few rare nights he was allowed to open his bar, reporters and camera operators showed up and chased off his customers, many of whom were not publicly out. Things were not much better in Jongno 3-ga, another district in Seoul with a lot of gay bars. It seemed like homophobia spread faster and more widely than the virus did, quickly affecting the whole LGBTQ+ community, leaving it scarred and damaged.

Witnessing this happen before my eyes made me think of the 1980s AIDS crisis in the U.S. I believe that the world has learned a lot from that time, and that’s how we were able to take action fairly quickly decades later with COVID-19. But in other ways, I feel like the world has learned nothing from that time: LGBTQ+ people are still constantly put in positions of vulnerability, pain and discrimination.

Being gay in South Korea without the weight of a pandemic is hard enough. The country’s president, Moon Jae-in, used to be a human rights lawyer—but during a presidential debate, he said he opposes homosexuality. Over the last 20 years, anti-discrimination laws have failed to pass and become legislation, in large part due to the influence of anti-LGBTQ+ Christian groups in the country’s politics. While LGBTQ+ Koreans are blamed for this latest public health crisis, the society our politicians have built—one that lacks protection for the vulnerable and allows discrimination—should be of greater concern.

“It seemed like homophobia spread faster and more widely than the virus did.”

In light of these targeted attacks against queer Koreans, LGBTQ+ activists and human rights activists in South Korea worked quickly to minimize the damage on our community, while also working to stop the spread of COVID-19. They released statements and held press conferences to criticize the government for laying the blame on LGBTQ+ Koreans, suggesting solutions and demanding changes. The government, surprisingly, responded well: It began offering anonymous COVID-19 tests and came up with ways to protect patients and their personal information better. It was not just the queer community who benefitted from these adjustments—everybody did. Unfortunately, it took jeopardizing gay people’s rights and safety to make these adjustments. Human rights activists and foreign media also criticized, educated and pressured Korean media to make changes in its coverage of COVID-19 and our community. These days, it has become a lot more sensitive to the language used in COVID-19 stories (with the exception of Christian media platforms), but the damage has already been done.

Credit: Courtesy Heezy Yang

Gay bars and clubs are so much more than places where you can experience and enjoy nightlife—especially if you live in a country like South Korea without protections for gay people. In addition to being able to be who I really am and feel liberated, I made a lot of unforgettable memories in those places. To think that young adults have now lost the opportunities to experience what I experienced—not only because of the virus, but also the hate that came with it—saddens me. And the possibility that only the remains of these places will exist when the pandemic finally passes is truly devastating.

But while South Korea’s LGBTQ+ community might have been beaten up, we have not given up. LGBTQ+ activists and organizations continue to stand up against ignorance and hate, with the goal of finally legislating anti-discrimination laws. I will do my part with my voice, my art and the platforms I have, and I hope you will join us, too, in solidarity, showing and sending support.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra