Last year, Downtown Soccer Toronto (DST) released a sexy calendar to raise money for the Justin Campaign, a British-based sports charity aimed at educating children and fighting homophobia in sports.

The Justin Campaign was founded in memory of UK footballer Justin Fashanu. Before Fashanu came out in 1990 he was one of football’s brightest stars and the first black footballer to make £1 million. But no other athletes followed him out of the closet, and for eight years he was the UK’s only openly gay man in professional football.

Homophobia blighted Fashanu’s career until his retirement in 1997. His brother publicly disowned him, and Brian Clough, Fashanu’s team manager, barred him from training with the team when he found out he was gay. In 1998, a 17-year-old American accused Fashanu of sexual assault. The media erroneously reported that the police were out to arrest Fashanu, even though there was insufficient evidence to lay charges. Fashanu succumbed to public humiliation. In his suicide note he wrote, “I realized that I had already been presumed guilty. I do not want to give any more embarrassment to my friends and family.”

Why did DST go so far afield in the search for a recipient charity? The short answer is that there doesn’t seem to be a charity dedicated specifically to fighting homophobia in professional sports in Canada.

That absence may seem odd, but Avery Miller, a DST spokesperson, says Canadians do not share Brits’ near-obsessive passion for sports. And, until recently, most people involved with Canada’s gay movement seemed focused on winning legal rights. Gay politicos in the UK, on the other hand, tend to be more focused on turning hearts and minds away from homophobia than pursuing court cases and fighting for legislative reform.

“In the UK, things like soccer and rugby, whether you’re gay or straight, it’s engrained,” says Miller. “There’s more of a movement for gay people playing it. Whether they’re out or not, there are more gay people playing professional soccer than there are here.”

Tim Ridgway, the Justin Campaign’s communications officer, acknowledges how difficult it can be for professional athletes to be open about their homosexuality. “Pro athletes are not just coming out to friends and families,” he says. “They’re coming out to millions of people who don’t know them and who can and will judge them. It takes a really strong person to do that.”

A 2010 Leger Marketing poll found that 70 percent of Canadians say knowing an athlete’s sexual orientation would have no impact on the public’s appreciation of him or her. Just imagine what it would mean for gay people if there were out gay athletic heroes in the NFL, NBA, NHL and Major League Baseball. But just because Joe Public says it’s okay to be gay in professional sports, that doesn’t mean that athletes are eager to accept openly gay teammates, says Greg Larocque, 2011 Vancouver Outgames human rights chair.

“There’s this preoccupation of ‘I can’t have a gay guy on my team because he might try and cruise me.’ It is fear,” says Laroque. “Somebody checks you out and you start making your assumptions. And the guy may be married, have three kids and he’s not trying to do you in the locker room. I don’t think these things will go away until an athlete’s sexual orientation is irrelevant.”

Laroque says we simply don’t need a Canadian charity for the advancement of gays in sport. He says mainstream sponsors ought to cough up for openly gay athletes simply because it’s good business to do so.

“I think putting the pressure on the gay community to help finance athletes lets a sponsor off the hook,” says Laroque.

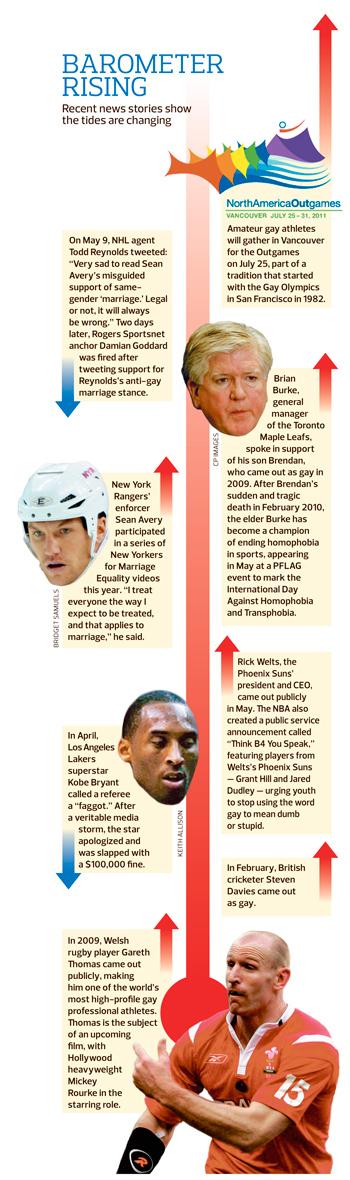

In 2009, Welsh rugby player Gareth Thomas became one of the world’s most high-profile professional athletes to come out publicly. Earlier this year, Thomas was joined by British cricketer Steven Davies in the thin ranks of out gay professional athletes. And slowly, there have been others.

Ridgway says that hearing elite athletes like Davies and Thomas say “I’m gay” helps, but the heavy lifting — eliminating homophobia in sports — is better done in schools. Still, he says, attitudes of management, players and even fans need to change for homophobia to be eliminated in sports.

“Having positive attitudes from management down will eliminate this issue,” says Ridgway.

Karin Lofstrom, executive director of the Canadian Association for the Advancement of Women and Sport and Physical Activity (CAAWS), claims that those positive attitudes are more prevalent than people might realize. “There are lots of gays and lesbians playing in mainstream sports. While they may be out in their team frame, they’re not out publicly,” she says. “They are leery of coming out publicly and losing sponsorship or losing their chance to get it.”

While there doesn’t seem to be a Canadian charity for gay athletes, that doesn’t mean there’s no support for them at all. Lofstrom points to Step Up! Speak Out! Ally Campaign for Inclusive Sport. It’s a website that features statements from Olympic silver medallist Mark Tewksbury and basketball player Danielle Peers. Lofstrom says it was created as a way of calling on the Canadian sport community to respect everyone, regardless of perceived or actual sexual orientation.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra