Two recent initiatives offer ways forward out of the global gay-rights impasse that often boils down to West-versus-The-Rest.

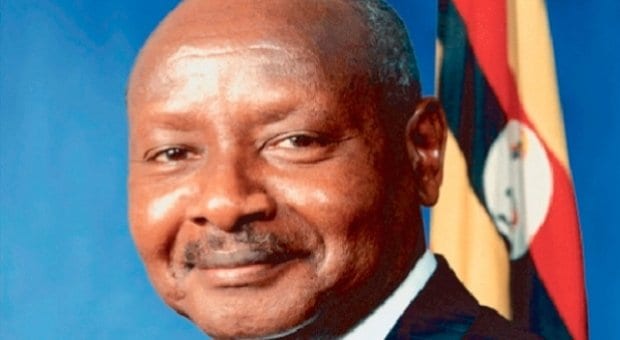

The first was a visit to Uganda by a delegation from the Robert F Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights to meet with President Yoweri Museveni about the Dec 20 passage of a bill that further criminalizes homosexuality.

Word from the delegation is that Museveni — who has called homosexuality “abnormal” and believes people are bribed or recruited into being gay — called the current draft of the bill “fascist” and planned to reject it.

A potentially promising step forward or a meaningless, conciliatory bone meant to appease the global village? Time will eventually tell.

The take-away from this diplomatic gander is that quiet, respectful conversation may achieve more concrete results in the long run.

Compare that to the predictable umbrage taken by Uganda’s parliamentary speaker, Rebecca Kadaga, when, in 2012, Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird very publicly took her to task over her country’s gay-rights record. Kadaga stormed home to press for passage of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill.

So said, so done a year later, and all that now stands in the way of the bill’s full enactment is a stroke of Museveni’s pen.

The reason pen has not yet been put to paper, is, in part, because of the collective efforts of governments, human rights groups and online campaigns that buttress diplomatic envoys with indicators of outrage to support their quiet calls to rethink legislated persecution.

The deal is often best sealed behind closed doors, where leaders can save face and make concessions and better decisions away from the heated atmosphere of political grandstanding.

The battle is an uphill one. Homosexuality is often seen as a Western construct, an extension of the colonialism and imperialism that African, Asian, Latin American and Caribbean societies have historically navigated.

Homosexuality is just another front in the ongoing battle involving issues of sovereignty and self-determination, a push-back against being told what to do and how to be.

Which brings me to the second initiative: an open letter that a former Mozambican president wrote to African leaders in the midst of mulling future development priorities.

Joaquim Chissano identified the sexual and reproductive health and rights of the continent’s people as a critical issue.

“This simply means granting everyone the freedom — and the means — to make informed decisions about very basic aspects of one’s life — one’s sexuality, health and if, when and with whom to have relationships, marry or have children — without any form of discrimination, coercion or violence,” he said.

While we are somewhat aware of the work of gay and other human rights organizations on the ground in Africa, we are often jarred when we hear heads of state, sitting or former, weigh in positively on an issue that is ridiculed and rejected.

Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe’s homophobic outbursts are far better publicized.

We need to hear more often from the continent’s public figures, like Chissano and Zambia’s first lady, Christine Kaseba-Sata, who last year called for the silence around men who have sex with men to be broken and for discrimination against sexual minorities to be eliminated.

“As an African who has been around a long time, I understand the resistance to these ideas,” Chissano says. “But I can also step back and see that the larger course of human history, especially of the past century or so, is one of expanding human rights and freedoms. African leaders should be at the helm of this and not hold back. Not at this critical moment.”

We need to listen to these potential gay-rights game-changers, even as Western envoys quietly lend their support behind the scenes.

Natasha Barsotti is the staff reporter at Xtra Vancouver.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra