Adrian Lomaga, the second Canadian gay man to challenge Canada’s blood-donation policies in court, withdrew his lawsuit against Héma-Québec April 1.

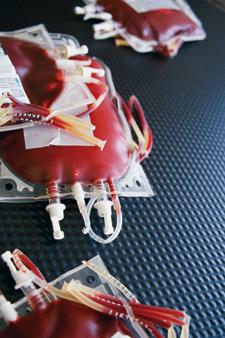

In a statement, Lomaga said he dropped his case because the Canadian Standards Association (CSA), an independent body that consults with leading experts, is considering changing its recommended blood deferral period for gay men to five years. As it stands, a man who has had sex with another man even once since 1977 cannot donate blood.

In an interview with Xtra, Lomaga says he doesn’t want to be cocky because there is no guarantee blood donation policies will change. “I’m cautiously optimistic, let’s put it that way. I think I’ve been successful to get blood associations to admit the deferral period is unsustainable. I’m not saying they’re going to change anything. I’m saying they will likely change,” says Lomaga.

While CSA doesn’t have final say, it holds a lot of sway. This winter, Canadian Blood Services’ (CBS) vice-president, Dr Dana Devine, said in an interview with Xtra that one route activists could consider taking is pressuring CSA. And even though Health Canada can overrule the CSA, having an authoritative organization like it on board would be a significant ally.

Something else Lomaga’s team took into consideration was an Ontario Superior Court ruling last fall that said the current MSM blood donation deferral was not discriminatory. If the team had lost in Quebec Superior Court, it could set an unfavourable precedent in two jurisdictions.

Lomaga launched his case in 2005. If he had proceeded, he would have had to prove that decision-makers acted in a discriminatory way at that time. To show that executives knew that a shorter deferral period posed no additional risk to the blood supply, he would have been able to use only the science that was available as of January 2004, predating any knowledge that has emerged through the Freeman case, the McLaughlin report and many journal articles that have urged the MSM blood deferral be changed.

Should Lomaga take up the torch again, he can build his case based on the science available on the date of launch. And by then he hopes, he will have more community support. “If I need to start up a new lawsuit, I will have extra scientific evidence and more support. And it certainly won’t take five or six years to go to trial,” he says.

Julius Grey, Lomaga’s lawyer, says people should wait and see what the CSA does in the coming months. “Because of the Freeman case, we had to go to the Superior Court level. The Superior Court would have likely followed the Freeman case. Therefore we would’ve had to go higher to have a chance, which would be the Court of Appeal. That would’ve meant more time than the new standards to be proclaimed,” says Grey.

Helen Kennedy, executive director of Egale Canada, says changing the MSM deferral period to five years would be a big jump for Health Canada even if CSA recommends it.

Doug Elliott, who represented the Canadian AIDS Society in the Freeman case, says there will be some people in the gay community who will want change immediately. But in this case, he tells people, “we gotta walk before we run.”

“People have to get used to [the idea that] change is a good thing and that it doesn’t have to hurt safety,” says Elliott.

Elliott also says change to the current MSM blood donation deferral is necessary. As it stands, a heterosexual male who was 16 in 1977 would now be 50. If this male had had one, and only one, homosexual experience in 1977, he would still be banned from donating blood today.

Elliott says the rule encourages donor defiance because people may perceive the question as a joke. “Any person who looks at the question today, especially young people, it looks ridiculous. I knew we were going to reach that point where it would change. Can we still use this question in 2077? If people feel the questions are stupid, they’re going to fill them out as they like,” says Elliott.

Elliott also says motivating factors behind a discrimination case are difficult for the average Canadian to understand. He says that for the average Canadian, words like “protecting public safety” will allow for drastic, even discriminatory, actions because people don’t expect rationalization. They trust the authorities are doing things to protect public safety and there’s no reason to question.

“From a scientific point of view, it does make sense to say some gay men carry HIV and could result in contamination in blood supply. But on the other hand, 1977 is junk science. The only scientific way to protect supply is to get gay men to cooperate with you. If it doesn’t get cooperation, it’s not going to work. Cooperation is a process that motivates human behaviour. You can’t force gays. You have to persuade them. If you ignore the issue and lecture them, saying ‘Don’t give blood because you all have AIDS,’ well, that’s not going to work,” says Elliott.

HQ spokespeople declined to comment. A CSA spokesperson was unavailable for comment by press time.

Lomaga encourages people to donate money to Egale Canada to help pay for the legal costs associated with his case. To do so, check out egale.ca/donate. Please mark your donation to “Adrian.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra