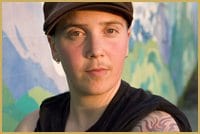

GENTRIFIED OFF THE DRIVE?: 'Either there are more middle-class lesbians on the Drive, or really the number of lesbians has gone down,' says Teya Greenberg, noting the drop in young, punky dykes. Credit: James Loewen photo

When Denise Sheppard and her partner decided 14 years ago to pull up their Ottawa stakes and move to Vancouver, they called The Book Mantle, a lesbian-owned bookstore on Commercial Dr looking for signs of lesbian life.

“We were moving to a city where we had no contacts,” recalls activist journalist Sheppard. “We wanted to rent in the right area, and where I like to live is in my community.”

Not only did the shop’s co-owner, Bonnie Murray, tell Sheppard she had called the right neighbourhood, she also invited Sheppard and her partner to stay in the basement apartment of her home until they found digs of their own.

“This woman had no idea who I was. [She] offered her home to my ex and I, and we ended up staying for two weeks until we found our own place on the Drive. That’s such a testament to the queer community and the Drive when a stranger who owns a bookstore opens her house to two strangers. I felt lucky to have such a positive experience,” says Sheppard, still sounding incredulous more than a decade later as she remembers the generosity of the offer.

The Book Mantle closed in 1996, but Sheppard, who has moved some five or six times to various Drive addresses since that initial welcome, says the area was her idea of gay heaven at the time. Ottawa was the appetizer, but Vancouver’s Drive district was the equivalent of a queer Belagio buffet, she says by way of analogy.

“I’d never lived in a neighbourhood where queers seemed to outnumber heterosexuals. There was such an ability to be free, there was a freeness in dykes holding hands in public. It was very different in Ottawa [where] we got yelled at. I had a lot of friends who were hospitalized [there]. There’s been some of that here too, but there was a difference between the homophobia that existed in Ottawa, and the numbers [of queer people], compared to here. I’d never been surrounded by so many queers.”

Gay couple Jim Smathers and Rob Cameron, one-time West Enders, describe an almost similar experience when they decided to buy a home on Frances St, just off the main Drive thoroughfare. They happened to look out the window of their new place only to see someone walk into their moving van and begin taking their stuff out of it. They initially wondered what was up, but soon realized it was a friendly neighbour come to give them a hand.

“That really gives a feeling for what the people are like on the Drive,” says Smathers, an elementary school teacher. “In other areas, I haven’t found people that open, [that] willing to help. She hadn’t even met us yet and she was willing to help us move in.

“She wasn’t queer herself,” he notes, adding that “all the people we met in the neighbourhood have been incredibly open and welcoming of us as a gay couple. We’ve never had any issues with that.”

Mary Brookes, now a veteran Commercial Dr resident having lived there for 20 years, says there’s always been a general level of acceptance among those who lived and congregated here, with the understanding that everyone was just trying “to make their way in the world, and you don’t kick the step out from under somebody.”

“I don’t remember anyone showing any open hostility. I mean, nobody [queer] was walking around arm in arm kissing in the park, like we can easily do now. But it was obvious who was queer and who wasn’t, and there was a definite level of acceptance,” Brookes recollects.

She also remembers the Drive looking and feeling a lot different from its contemporary incarnation. Non-existent were the range of restaurants and clothing stores of its current, commercialized landscape. Instead, there were myriad and more independently owned Mom and Pop establishments.

The Drive was edgier then, she asserts.

“Commercial Dr was the rough part of Vancouver. Even the Downtown Eastside wasn’t considered that scungy at that time. We had the rough edge, always low-income. It was a cheap place to live.

“And as with most cities, that’s where the dyke community establishes itself,” she notes, “because we’re women, we earn less, all of that against us. That’s where the [Drive’s] woman stamp came from. It was purely the affordability.

“That was certainly not the case in the West End, or Kits, or Marpole,” she continues. “Geographically, it was the cheapest place to live. There were lots of houses with three or four illegal suites, which made it really easy to find a place to live.”

A safety net is the symbol that comes to Brookes’ mind when she remembers the area she moved into in 1987.

“Thank God there were women before me who did the work for me to be able to move to an area that was safe. Not exactly to be openly queer, but it was one of those safer places in town to be,” she reflects.

But there was still a furtive quality to meeting and hooking up with other women.

“We’re talking 20 years ago. It was a lot more of that make-eye-contact, and that ‘I know that you know that I know’ which is kinda fun. I have to say, I really miss that,” Brookes admits with a smile and an implied wink. “I miss that edge to it, when we were bad, when we weren’t a fashion statement. I never wanted to be normal and good. It wasn’t this big oneness. There was a definite dress style then. Ripped-up jeans and lumberjack shirts.”

Brookes pauses.

“I’ve never been a fashion plate, but I really hated that look,” she says with a hearty laugh.

The Drive also used to be a very political part of town, Brookes notes, claiming this is not the case as much anymore. She recalls the now-defunct Lesbian Centre as a designated women-only space that did work around issues of discrimination, and housed a drop-in facility and coming-out group.

And it wasn’t just queer issues that got an airing. Many dykes also organized workshops by and for themselves around issues such as racism and ageism in efforts to “unlearn” bad habits where those and other -isms were concerned.

“If we were attempting to be representative as a group, we needed to do a lot of homework,” says Brookes.

Drive resident Setareh Mohammadi remembers her home being a nexus for all sorts of politically passionate women, including queers, who organized around indigenous and immigrant rights, refugee concerns, anti-poverty and anti-racism.

“My sense of queer women, of different genders was a good one. I was around nine to 11, a time when I was really beginning to find more words around sexuality, and understanding and feeling at that age that I was a little bit on the queer side.”

Mohammadi says many of those same causes that occupied activists in the mid-’90s still resonate today, but like Brookes, she has observed quite a sea change in the level and intensity of, and commitment to, activism-not to mention the overall social texture of the Drive.

“There’s more organizing around gender-queer issues. Not much about that in the ’90s. But even now, I don’t feel that sense of community the way I used to. There’s not as much organizing around gender across age or across race as you used to see in the ’90s,” she contends. “[Back then] there were rallies from Clark Park to Grandview Park. Commercial Dr and Broadway used to be shut down all the time for rallies, and you don’t see that anymore. It’s rare.”

Looking around her neighbourhood, Mohammadi says she’s seeing a lot more of an individualized, isolated style of living that is less political.

“More people get together and party, more people put on events which may be fundraisers, but you don’t see the political message as being very public, or involving not just one set of struggles, but many. There’s lots of events that celebrate queerness and queer parties and things like that. But you don’t see an event that’s very queer-friendly, but [also] works on immigration rights, or refugee [issues] or indigenous rights or stuff around the Olympics. They’re very detached from one another.”

Mohammadi says, for her, it’s not about privileging one identity or way of being over another. She says she would never call herself queer before seeing herself as someone who has come through a refugee experience or describing herself in other ways.

“I’m all of it, and definitely I defend all the communities I’m from,” she asserts.

Sheppard is on the same page.

“When I look at entertainment things on the Drive, in parks, in clubs, being queer is hardly all that I am. I’m able to go out and exercise the different types of person that I am in queer venues. It’s about being queer and something else. I really like how everything is evolving. You are queer and other things, and you can also meet queers who are into those other things.”

But like Brookes, like Mohammadi, Sheppard is disconcerted by the rapid changes to the face, feel and social interconnectivity of the Drive. And they all point unequivocally to the ongoing process of gentrification as the culprit.

A lot of people are being displaced and “kicked out,” says Mohammadi, who has run out of fingers to count the number of friends she has seen move away over the past two and half years. Many are people of colour, including queers of colour, she observes.

“That, to me, is most visible because that’s the community I come from, and what I hear and witness firsthand. Around my block are near-million-dollar homes going on sale, and this was an area that was more affordable to live in,” says Mohammadi who lives in co-op housing west of the Drive. “It was created by immigrants and native communities.”

She finds the displacement of long-time residents alarming.

Sheppard agrees that the area’s financial realities are “just terrifying,” and fears gentrification will have deep negative impacts on the ability of the Drive’s queer community to live collectively.

“More and more people are finding it less affordable, and it’s not like everyone is moving collectively to a new space.”

Teya Greenberg, who does community work around housing and homelessness, says as recently as six or seven years ago there was a more visible lesbian presence in the area, especially young punky lesbians. And while she still sees the Drive as a queer neighbourhood and space, the increasing lack of housing is making it prohibitive for queer women to live there.

But Greenberg says there is also the complicated question of what makes a visible queer woman.

“My reference point, six or seven years ago, [is that] there were more young, punky, dykey-looking women. So either there are more middle-class lesbians on the Drive, or really the number of lesbians has gone down.”

For her part, Brookes says when she thinks about the Drive, she sees it in terms of what it used to be.

“It’s not what it was, obviously. And it’s kinda sad. There are a lot of queer families now and, for some, this isn’t the place they want to raise their children. So forced out, pushed out, choose to move out, there are not as many older queers on the Drive as there used to be.”

Then again, she muses, her gaydar may be a bit off now.

“I’m not sure whether somebody is queer or not, if they’re young. They don’t have a big ‘L’ on their forehead. And they haven’t got their lumberjack shirt on,” she laughs.

“How the hell are you supposed to know?”

Rueful wistfulness aside, the Drive still stirs a sense of belonging, neighbourliness, safety, and community among those who call it home, or are just passing through.

It’s one of the few neighbourhoods Mohammadi feels comfortable walking with her partner, being open and “sucking face.” You might get stared at, she admits, but not endangered.

She also holds out hope for the Drive’s hard-earned reputation for harnessing and promoting a culture of resistance.

“It would be wrong to say there’s silence around what’s happening. People are very vocal, and you can go to any community meeting and hear those words gentrification and housing, and I hope racism will come up. You can see signs saying no to the Olympics, or shut down 2010, and still see powwows, and a lot of brown people. We’re not going anywhere, especially us queer ones.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra