SILENT NO MORE. All forms of representation are up for grabs, including cinematic, with the premiere of Shooting Geronimo.

Kent Monkman is carrying a lot on his shoulders. Consider that his exhibition of new work, The Triumph Of Mischief, opening Thu, Jun 7 at the Art Gallery Of Hamilton, consists of about 10 large paintings (some monumentally so, in the seven-by-nine-foot neighbourhood) and three video installations housed in glammed-up floor-to-ceiling teepees. For good measure, each of the installations are multichannel affairs featuring Monkman’s own films, including the world premiere of Shooting Geronimo, projected from chandeliers suspended in the middle of the teepees.

Just pause for a moment, and consider the enormity of the task of pulling this all together, and then consider that this exhibition is touring to venues in Victoria, BC, Winnipeg, Toronto and New Brunswick.

Monkman has still larger plans. “What I’m trying to do on this tour is to find maybe one or two paintings, or maybe more in [each gallery’s] collection to influence my work. So as I create new work, I can have a new piece with each venue. So the show will grow as it tours.”

The whole tour, therefore, is an everchanging site-specific installation.

In general, the show is conceived of as a new chapter in the unfolding saga of his drag alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. “The idea was that this was Miss Chief’s travelling ‘Gallery Of The European Male.’ So it’s playing on that idea of artist as showman, as ringmaster.”

Of course, much like the rest of Monkman’s work to date, it plays on many more ideas than that, chief among them the thorny (to be demurely diplomatic) issue of the colonization of Canada and its ladies-in-waiting, the erasure of native histories and the distortion of aboriginal representation. This is, of course, a minefield of a subject, and one that involves Monkman personally. He is a Manitoba Swampy Cree and his family history reflects the historical knot of Canadian colonialism: his mother is of English and Irish descent, and his father a Christian Cree who preached from a Cree-language Bible in northern Manitoba.

This personal resonance is the spark of his encyclopedic revisionist project, and one that Monkman hopscotches through with all the ease of a kid at play.

Talking to him about his paintings and his videos involves a whirlwind tour of references and cross-references that can get a little dizzying for the unfamiliar: The pompous ethnological ineptitude of figures like the 19th-century autodidact George Catlin (who made a career of painting the likenesses and rituals of native Indians), the patronizing romanticism of landscape painters like Cornelius Krieghoff (whose largely fictitious landscapes, heavy on sturm und drang, sold European buyers on the idea that North America was a vast untapped Eden) and, of course, the first couple of New World exploration, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. These were the figures responsible for shaping the public’s conception of America and Indians. In this brave new world, these characters, as misguided and condescending as they may have been, were the reporters on the front lines.

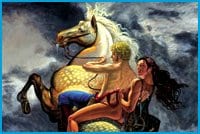

Monkman inserts Miss Chief into this tangled pictorial history and lets her work her glorious camp magic. Monkman’s work started out as a playful inversion of the stereotypes common in turn-of-the-century paintings. So he depicted hunky European boys helpless before Miss Chief’s wiles, stripped, tied to trees or forced to act out the bizarre and outlandish rituals of the White Man for the edification of the New World’s avenging angel in platform heels.

The further that Monkman got into this conceptual landscape, the more involved his paintings became. To say that his work is a riff on the works of men like Krieghoff and Catlin is not only a vast understatement, it somewhat misses the point. Monkman not only absorbs them, he subsumes their entire formative context — in this case, nothing short of the history of European Grand Manner painting. “The larger overarching narrative is something that continues to evolve,” says Monkman. “It’s a sprawling or ambling narrative which keeps opening as things evolve.

“There was this intent all along to grow them into more complex scenes, but I had to have the skill level up to speed in order to attempt that. But the whole idea all along was basically to be a history painter, and to talk about these missing narratives and these obliterated histories.”

Monkman began as an illustrator, training at Sheridan College and eking out a living creating storyboards for advertisements. He also has a background in theatrical set design. There’s no question, now, that Monkman has become a history painter. One look at his mammoth paintings shows how completely, successfully and, most importantly, how uniquely he has processed the idioms of history painting.

Big name collections have taken note: His work has landed in the permanent collections of the National Gallery Of Canada, Museum London and the Canada Council Art Bank, to name a few.

The kick in Monkman’s work lies in the kinds of insertions, revisions and references he makes. For instance, one of the centrepieces of the upcoming show is a giant Bacchanalian orgy scene, in which all of these inspirations and references clash and riot in a sublime 19th-century landscape: Against a Bierstadt backdrop, Nicolas Poussin meets Jacques-Louis David with a soupçon of Michelangelo-by-way-of-Picasso, in which all of Monkman’s stock characters of tribesmen, burly trappers and effete explorers are tangled in an orgiastic revel orchestrated by and whirling around (who else?) Miss Chief.

Cross-references, historical footnoting and art historical nodding do not guarantee good art. But Monkman is an adept juggler; his works are more than just simple quotations or send-ups. If that was all there was to his work — riffing, copying, quoting, reading up — then no one would care; they would just be overdetermined research papers. The art lies in what comes out the other side of all this visual and literary knowledge.

“Inserting an aboriginal way of seeing the world is what it’s about, but using this vocabulary,” says Monkman. “I’m doing it using this preexisting European language.” In other words, he takes this towering conceptual load of Western painting convention and tackles it on its own turf. His processing of these idioms is, in and of itself, a commentary on them: He makes us recognize just how much authority we invest in this art tradition.

But the most delicious aspect of Monkman’s co-opting of history painting is how delicately he subverts it. He uses its authority to propose an alternate mythology of America, one where all the brutal injustices of colonialization have been camped and cheekily redressed… in high heels and a great big silky pink wrap.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra