Before I grew my mullet over the past year, I had never let my hair grow much longer than a few inches. But when the pandemic started and haircuts became far more inaccessible, people like me made the most of our time alone to experiment with brave new styles in naive anticipation of the new looks we’d be stunting on our first nights out together again.

After a few months of growing my hair out, my partner, who for years worked as a hairstylist, bleached my ends platinum blonde and cropped the sides of my head last February, allowing my new length to flow down the back of my neck. Feeling like my ultimate Debbie Harry fantasy, I couldn’t wait to run out and belt Blondie songs at karaoke, my dark natural roots offsetting the perfect bottle-blonde of my hair’s two-toned glory.

Both of those dreams were crushed within days of gaining my new style: COVID-19 shut down all my karaoke hangouts (along with the rest of the world), and the release of Netflix’s Tiger King led everyone to believe I was channeling Joe Exotic for fashion inspiration. Of all the trauma we’ve collectively been through over the past year, I still, however selfishly, consider this comparison especially tragic.

As the pandemic kept us stuck inside and out of places like hair salons, the mullet’s resurgence over the past year has been undeniable. There’s Rihanna’s slick and edgy styling and Billie Eilish’s “accidental” two-toned modern take; then there’s Miley Cyrus, who followed in her father’s footsteps with her exemplary Blondie-meets-Joan Jett classic rock style. On TikTok, the #mullet tag currently sits at 2 billion views, featuring videos of mostly Gen Z-ers cutting their overgrown quarantine locks to achieve business in front, party in the back. RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 12 finalist Crystal Methyd was able to build an entire persona around her mullet. And there is even a festival dedicated to the hairstyle held annually in Australia.

But just because the mullet is popular again doesn’t mean that its cultural impact has been given its due credit. The hairstyle has undergone waves of cultural and political transformations—from a musty relic of 1980s hair-metal bands to a backwoods country haircut to its ubiquitous appeal today—all fuelled by its oft-forgotten queer adjacency.

“As the pandemic kept us stuck inside and out of places like hair salons, the mullet’s resurgence over the past year has been undeniable.”

Early examples of mullets appear throughout history; even Homer wrote of men who wore “their forelocks cropped, hair grown long at the backs” in The Iliad. In its early stages, mullets were grown for purely utilitarian purposes: To keep necks protected from cold and sun while keeping eyesight unobstructed. As a result, the style was reserved for working-class men performing physical labour. It wasn’t until the 1970s, when people began rejecting the clean-cut suburban fashion of decades prior, that the mullet underwent a style revolution.

It was a decade into the second wave of feminism that the first examples of the feminized mullet began to flip the idea of who the haircut was for. Jane Fonda, in her breakout role as call girl-turned-detective Bree Daniels in the 1971 film Klute, sported a sharp brown shag cut. Meanwhile, “I Am Woman” singer Helen Reddy, along with Florence Henderson as Carol Brady in The Brady Bunch, started to domesticize the hairstyle and contributed to its popularity among women.

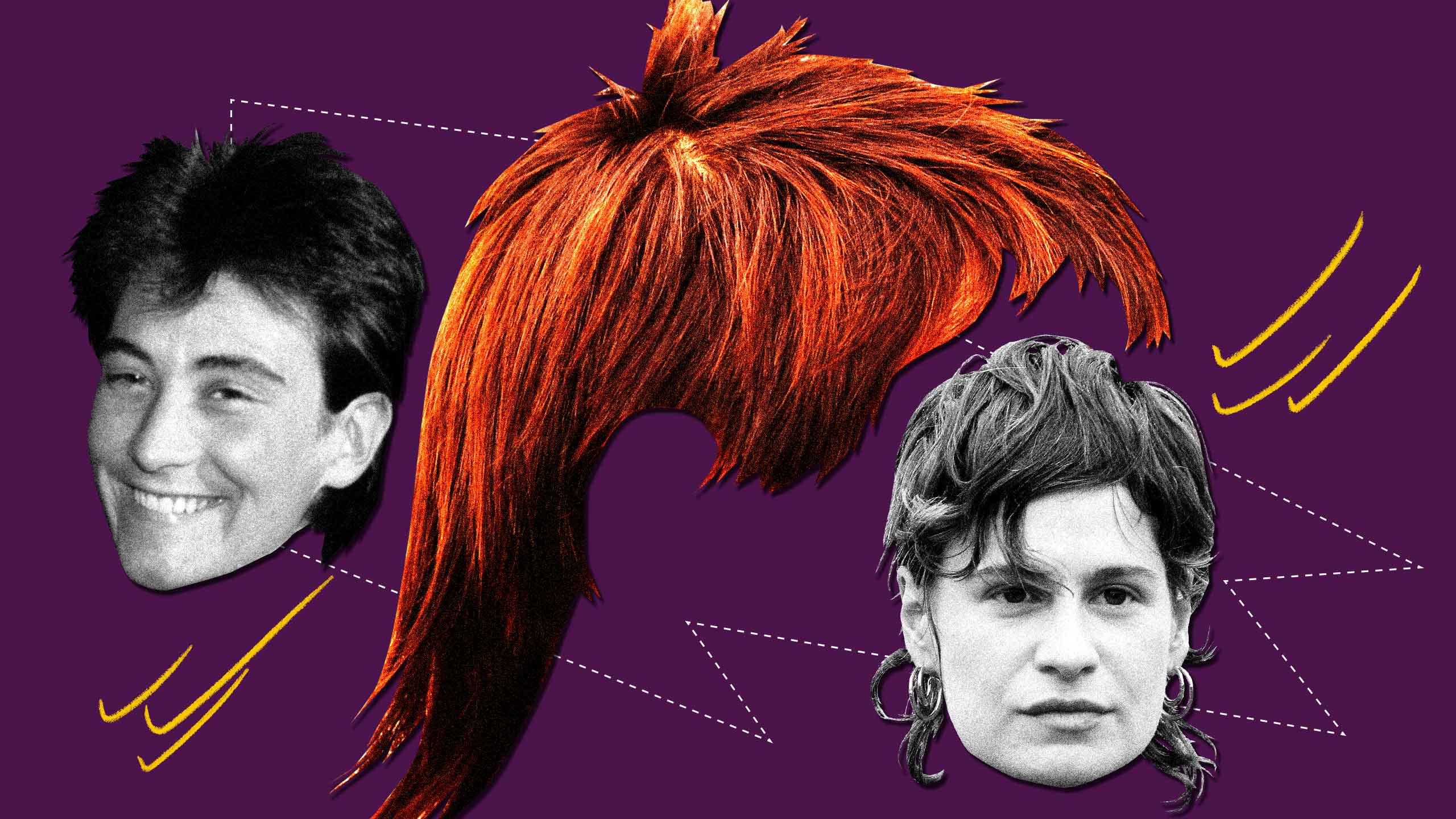

But it was David Bowie’s debut of his Ziggy Stardust alter-ego in 1972 that blew out any gendered confines of the mullet. Dressed in the most avant-garde fashion and topped off with a fluorescent orange dye job, Bowie used his mullet to place his interstellar character beyond the earthly confines of gender. Audiences didn’t know what to make of Bowie’s androgynous performance, and the hairstyle became distinct among people who were beginning to rethink their own ideas around gender. The Ziggy Stardust mullet was a point of reference for the sparkly glam-rock stars throughout the ’70s, many of them known for their gender play. From hard rock band New York Dolls to trailblazing female rockstars like Joan Jett and Cherie Curie of the Runaways or Suzi Quatro, the mullet was a calling card for those looking to reject mainstream beauty standards, and was perhaps the most widely accepted form of androgynous fashion.

“I’ve noticed in past months how people see me differently—even behind my face mask—as my hair continues to grow longer.”

Today, the mullet has become something of a queer rite of passage. New Jersey-based music and culture journalist Jade Gomez, like me, happened to start growing out a mullet of her own last February. She agrees that the hairstyle’s current popularity could not be severed from its queer history. Gomez has long experimented with alternative fashion since her teen years, heavily influenced by rave, hip-hop and grunge styles. But when her hair got to the longest lengths it had ever been, she was concerned that the image she was portraying did not match her true identity. “With my anxiety, I’m always questioning myself over how people see me,” she says.

When a friend of Gomez’s cropped her hair into the mullet she desired, Gomez finally felt settled in her queerness. Since growing her mullet, she feels a freedom to experiment with her look like never before. “Ever since I got my mullet, I feel more comfortable knowing that someone on the street will see me as queer,” she says. “I get more compliments, people treat me differently, like I’m finally seen as one of them. It really helped bring my [queerness] in full circle.”

I feel it, too. When I’m out on a walk or getting groceries, I’ve noticed in past months how people see me differently—even behind my face mask—as my hair continues to grow longer. While I identify as non-binary, I never thought that I was truly femme-presenting until the cashiers at the grocery store started to say, “Have a good day, ma’am” on my way out. I’ve even heard strangers change their pronouns for me mid-conversation, covertly switching between referring to me as both “sir” and “ma’am” over the course of a few sentences. Each time that happens, I smile behind my mask, pleased that I’ve successfully made them reconsider how they view my gender expression in real time.

Despite the gender-queering style of mullets in the 1970s and its proximity to butch lesbians like kd lang and the Indigo Girls in the late ’80s, it was later reappropriated by a polar opposite demographic: The macho man. From Billy Ray Cyrus’ radio smash “Achy Breaky Heart” to David Spade’s white-trash caricature in the 2001 movie Joe Dirt, the mullet picked up subtle classist connotations that it is still shaking off today.

“Queer people have regularly reappropriated that which is considered uncool—turning a dusty relic of a hairstyle into an unexpected fashion trend.”

To those who are culturally out-of-touch, mullets are still considered about as country as a Davy Crockett-style raccoon skin hat. But, as Gomez notes, queer people have regularly reappropriated that which is considered uncool—turning a dusty relic of a hairstyle into an unexpected fashion trend. “The reclamation [of mullets] by queer people is so powerful,” she says. “We’re allowed to experiment with our identities by reclaiming what the mainstream considers ugly.” A decade ago, you’d be hard pressed to find mullets outside a Tegan and Sara concert. But seeing the hairstyle anoint the heads of queer personalities like Troye Sivan, Lizzo, Christine and the Queens, Barbie Ferreira and Cameron Esposito has helped to cement the mullet’s iconically queer image.

Culture and fashion has long been shaped by marginalized communities. A style that wasderided by straight culture over the past few decades gave queer people the freedom to reinvent it into a completely new look—onethat is now the featured hairstyle in fashion magazines everywhere. While the mullet in the present day is so ubiquitous that our social feeds are inundated with people cutting their overgrown quarantine hair into the simple and stylish DIY haircut, it is time that the mullet got its due queer credit.

The power one hairstyle can have.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra