Tegan and Sara Quin – Canadian recording artists, lesbians, twins and animal rights activists – say they were first exposed to animal activism in grade six when their class watched a documentary on the controversial seal hunt that occurs annually on ice floes just off of Canada’s east coast.

“The hunters clubbing the seals and then skinning them was horrifying to witness,” Sara recalls.

The Quin twins recently teamed up with the US-based People For The Ethical Treatment Of Animals (PETA) and the group’s youth-focussed division peta2 to call for an end to the government-sanctioned seal hunt.

“I do feel like there are alternatives to killing animals for food and materials,” says Sara. “Just like the gas and oil industry, I feel like we are not moving quickly enough toward these alternatives.”

Is it just a coincidence or does the animal rights movement attract an unusually high percentage of queers? According to PETA’s openly gay vice president Dan Matthews, many queers are drawn to animal rights activism because they see a connection between violence against queers and violence against animals.

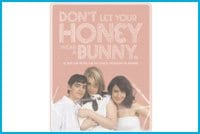

Lesbian feminist punk popsters Le Tigre are also lending a hand to peta2. Band members JD Samson, Johanna Fateman and Kathleen Hanna are featured in the organization’s current antifur public service campaign.

In the print ads, Samson and Hanna are pictured flanking Fateman, who is holding her pet rabbit, Karen. The ad’s tagline is, “Don’t let your honey wear a bunny,” which the band members apparently came up with themselves.

But Tegan, Sara and Le Tigre are hardly the only queers to get involved with animal rights activism. Melissa Etheridge and then-girlfriend Julie Cypher were the first same-sex couple to be part of PETA’s “I’d rather go naked than wear fur” campaign. Drag star RuPaul has graced the cover of PETA’s animal-friendly cosmetics shopping guide. And who could forget Canadian crooner kd lang’s high-profile antimeat campaign back in the early ’90s?

Matthews tells a story of growing up in what he calls a “white trash neighborhood” in Southern California, where other kids would shoot stray cats with BB guns for fun. Even though pets were not allowed where he lived, he often brought strays home in order to rescue them from the abuse.

But it wasn’t until his teen years that he really made the connection between his gayness and animal rights. He remembers being beaten up for being a punkish and closeted gay kid, lying on the floor while his attackers laughed at him. Around the same time, he went on a fishing trip with his father. He remembers catching a “big, ugly flounder.”

“Someone stomped on the fish to get the hook out. There was blood all over the place, and the fish was desperately panting and breathing heavy while everyone was standing around laughing. All I could think was, ‘That’s me, but now I’m the bully.’ I stopped eating fish immediately.”

Local trans activist Mirha-Soleil Ross had a similar epiphany as a teenager. Ross comes from a long line of farmers and hunters, but says it wasn’t until she saw an animal caught in a trap that she saw animal cruelty up close.

“It was disgusting,” says Ross, “and yet I realized I was wearing animals and eating animals. It was at that point that I decided to stop.

“Of course, my parents didn’t understand what it meant to be a vegetarian. I didn’t even know any vegetarians. So they thought I would die in a month’s time. But I’m still here.”

Ross credits her activism in the animal rights arena with raising her political consciousness around other issues, including queer rights and the rights of sex workers. She adds that if there is a connection between animal rights and sexual minorities, it is in the way society “denatures” them.

“We have domesticated animals, reflecting our own withdrawal from nature. And when it comes to sexual diversity, society wants us to reject something in ourselves that is natural. Sex is a biological need that is mentally, physically and psychically necessary for our well-being. We feel uncomfortable when a dog humps a leg, yet it’s completely natural for them.”

Ross views the connection between animal rights and queer rights as a very personal one.

“I am just extremely uncomfortable with seeing another being suffer, whether human or not, whether it’s an animal stuck in a trap or [a queer person] being beaten over the head with a baseball bat.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra