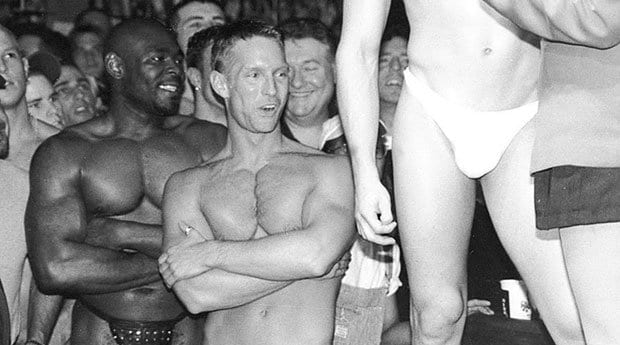

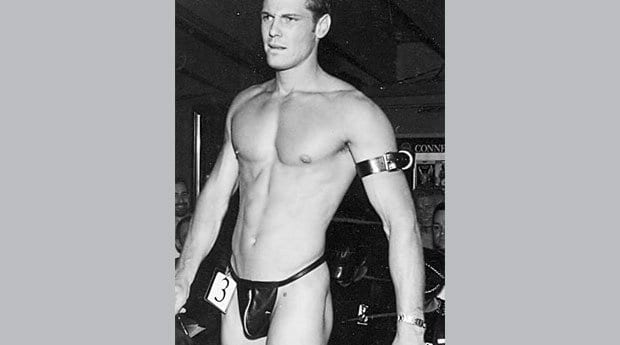

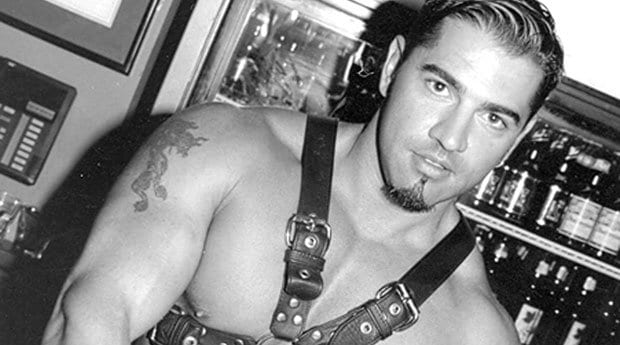

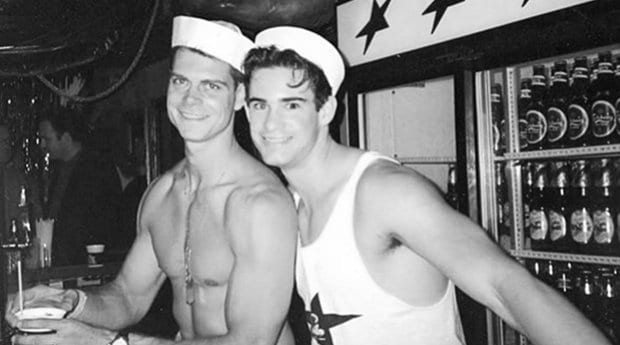

Faces (and bodies) of Woody’s staff and patrons from years gone by. Credit: Photos courtesy of Woody’s

Faces (and bodies) of Woody’s staff and patrons from years gone by. Credit: Photos courtesy of Woody’s

Faces (and bodies) of Woody’s staff and patrons from years gone by. Credit: Photos courtesy of Woody’s

Woody’s is a sacred space.

It’s a statement that could be seen as controversial to some, but for many people in Toronto’s queer community, the Church Street institution is much more than your average neighbourhood watering hole. And on a busy Friday or Saturday night, with the establishment’s four bars buzzing with life, the space possesses both a vibrancy and relevancy that belies its 25 years of existence.

“For queers, bars are our temples; drag queens are the priests and DJs are the choir,” says Mitchel Raphael, photographer and former Fab magazine editor-in-chief. “Woody’s is the holy of holies of gay bars. [And] much like the best of true religious institutions, it has been incredible at giving back to the community it serves — whether it be funding for the arts or donating money for political battles like same-sex marriage.”

Patricia Wilson, bar manager at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, agrees. “Woody’s was everything the world around us was not for the queers. Without that bar, the people in the community would have been like zombies wandering the streets looking for compassion, strength and sex.”

Tracing a true lineage of the bar requires going back to the late 1970s, when the city looked quite different. Long before Pride festivities brought huge crowds to Church Street, most of the city’s gay establishments were sprinkled along Yonge Street, an area Torontonians rather dubiously referred to as the Sin Strip.

It was around this time that Alex Korn, a heterosexual entrepreneur and owner of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel on Charles Street, met Ward Hagar, the front-desk manager of the same facility. Korn, who had been in the bar business for years, forged a fast, if unlikely, friendship with the openly gay Hagar.

One evening, Hagar invited Korn out to some of the city’s various queer establishments. Korn was surprised by what he discovered.

“He took him on a tour of the gay bars in Toronto, and there weren’t a lot of nice options available,” says Dean Odorico, general manager at Woody’s. “So [Korn] saw an opportunity … He wanted to open a gay bar to be proud of and travelled to New York City for research. And [partnering with Hagar in 1983], he opened Chaps on Isabella Street and put a lot of money into it.”

A dance space with a restaurant and a bar downstairs, Chaps was an immediate success that attracted large crowds and had a huge impact on the city’s gay scene. But within a year of the bar’s opening, Hagar would succumb to an AIDS-related illness; the death had a tremendous impact on Korn. The bar began doing benefits for the Toronto People with AIDS Foundation.

“It was a horrible time,” Odorico says. “But it was [in those spaces] where all the activism came from during the AIDS crisis. The money was raised in the bars and the clubs.”

Korn and his wife, Dorry, established a resort in the Muskokas called Ward’s Retreat, where people living with HIV/AIDS could rest and escape the city. Still, he felt that there was more he could do.

“He wanted to open another bar that was more community based,” Odorico says. “He had done so well with the community that he wanted to continue to give something back. So that was the mandate when he got [our current] space.”

Korn chose a location on Church Street that had previously been a gay piano bar called Jingles. At that time, aside from a few queer staples like The Barn and 457, the area was occupied mostly by production facilities for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation or bars and steakhouses that catered to industry workers and the Maple Leaf Gardens crowd.

Hiring a number of young staffers with experience in community establishments, including current general managers Odorico and Steven Clegg, Korn wanted the new spot to be different in a number of key ways.

“When we opened [in June 1989], pretty much any gay bar wouldn’t have any window openings or anything like that,” Clegg says. “It would be blacked out or brick walls because of safety concerns. That was one of the things we did early on, open up the windows. People wouldn’t necessarily want to sit in them in the early days. They just didn’t want to be seen in a gay bar. And that was part of the evolution of Church Street. People were more willing to be seen.”

On the first night the bar was open, staff passed around donation baskets for the AIDS Committee of Toronto (ACT), with Korn matching the amounts given by patrons. The bar later introduced a regular Staff Night on Mondays, with tips going to ACT and donations again being matched by Korn.

The first version of Woody’s was a quarter the size of its current space. It was made up of two rooms, a kitchen, an office and a beer cooler in the back. Brunch was served on Sundays, and the capacity was small — roughly 100 people. The bar deliberately established itself as edgier than the more traditional gay dance clubs in town.

“Previously, there had only been piano bars or dance bars,” Clegg says. “We weren’t either [of these], so we were kind of a new animal. We were the only bar that had alternative music, which was new wave back then. That was the music we all listened to at the time. Plus, we didn’t play disco and dance music, which worked really well for us.”

Wilson remembers the early years fondly.

“There was a middle bar and sawdust on the floor. It was an eye-opening experience,” she says. “I walked into [the bar] on my own the first time, and I was greeted by the bartender as I walked in with ‘Hey! You must be Patricia, the new person Sky [Gilbert] hired to work at Buddies. They’re all in the back.’”

“So friendly and welcoming over 20 years ago, and it’s still the same.”

Woody’s became immensely popular, with beer sales rivalling those of the Skydome (now the Rogers Centre) and the neighbouring Maple Leaf Gardens. At one point, the bar was selling the third-highest amount of beer of any establishment in Ontario.

“It was busy every day,” Odorico says. “In those days, gay bars were like the epicentre of the community. That’s where you met guys, and that’s where you met friends. Gay bars and bathhouses were the two biggest options.”

The bar expanded and began to incorporate various forms of live entertainment. The Best Chest Contest on Thursday nights was the first to appear, which drew in the college-aged crowd, followed soon after by regular drag nights and a rotating group of DJs.

With the departure of the CBC and the closure of the Gardens, large sections of real estate along Church became available to entrepreneurs within the community. Crews opened across the street from the bar, and Xtra moved into the offices above Pusateri’s. Many of the old-style steakhouses transformed into gay bars, like Hair of the Dog and what would eventually become O’Grady’s, Flash and Church on Church.

Korn soon took over the space next to Woody’s with the intention of creating a two-storey dance bar. City bylaws prevented him from doing so, which led to the creation of the nautical-themed bar Sailor.

“That’s been a big part of our work,” Clegg says. “Not working around the rules, but working with the rules that [the City of Toronto] gives us. Like smoking bylaws — it changed so many times over five years. And every time, we would make changes and evolve.”

The bar attracted more attention in the early 2000s when the producers of the US version of Queer as Folk modelled the show’s fictional pub on it. They retained the name, used exterior shots of the bar and constructed a replica of it on a soundstage in Mississauga.

“I remember the first Pride after the show aired and became a hit,” Clegg says. “It was just astounding, the people who came up and stood under the awning to have their picture taken. There was this huge stream of people wanting to do that.”

The bar has continued to evolve in the last decade, hosting fundraisers for various local sports teams, visiting theatre companies and TIFF parties for celebrities. And a number of famous faces have stopped by over the years.

“Billy Zane was here for a movie of his,” Odorico says. “So was Billy Corgan from Smashing Pumpkins and the Scissor Sisters. Chi Chi LaRue and a lot of gay pornstars.”

“Ian McKellen was here,” Clegg says with a laugh. “I wasn’t here that night, which really annoyed me.”

Though other businesses in the Village face challenges because of the advent of dating apps and internet hookups, Clegg is optimistic about Woody’s future.

“I don’t think [the importance of a physical space] is diminishing,” he says. “Toronto has grown as a city, and other areas have popped up, and that’s all positive. I think there’s a need for them, and I think there’s still a need for this area, and there will always continue to be a need for it.”

“The social aspect is still very, very important in people’s lives. They want to go out and meet up and have fun together. Certainly there are more options for people to hook up and explore that. But I don’t usually hear people say, ‘I met my boyfriend or I met my husband on a hook-up site.’ So I think better connections are made here, and they still are.”

“Everybody said we’d be closed within six months, and we sorta outlived them all. So I’m not worried.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra