“Ask Kai: Advice for the Apocalypse” is a column by Kai Cheng Thom to help you survive and thrive in a challenging world. Have a question? Email askkai@xtramagazine.com.

Dear Kai,

I’m a queer woman in a relationship with another woman. We have explosive chemistry in every sense of the word: High passion, amazing sexual connection and also a very tempestuous dynamic. We often have big, loud fights. I think part of it is that we’re both from families where conflict was always addressed directly. I’ve never felt afraid of my partner or like I’m in danger, and we almost always make-up after a fight—usually by having delicious sex.

To be honest, I kind of find this whole dynamic pretty hot, and she says she does too! But recently a friend of mine (who is very WASP-y, while my partner and I are both women of colour) saw us arguing and had an “intervention” with me. She said I’m in a “potentially abusive” relationship. I told her she was mistaken, but she kept insisting that “a partner should never yell at you.” For real? What’s that about? Should I take this seriously?

The Loud Woman

Dear Loud (may all women find their inner loudness!),

I could never presume to tell you whether or not your relationship is abusive, especially since I don’t know you in real life. But then, perhaps this is the problem highlighted by your letter: That generally, people shouldn’t try to define relationships that they are not in—or at least should do so with a degree of caution. What I hear you saying, Loud, is that you and your partner like your relationship on its own terms, and neither of you feel like anything harmful is happening. Taking that at face value, I encourage you to stand—loud and proud—in your truth.

In an era where terms like “abuse” and “trauma” are used frequently, especially in queer and trans communities, it’s important to get some clarity on what we mean when we use this language. This isn’t to say that we should stop using those words—on the contrary, it’s a good thing that we have access to the language we need to name harm. However, with powerful language also comes the responsibility to speak thoughtfully and carefully. So let’s be thoughtful: What could your friend mean when she says she thinks your relationship is “potentially abusive”?

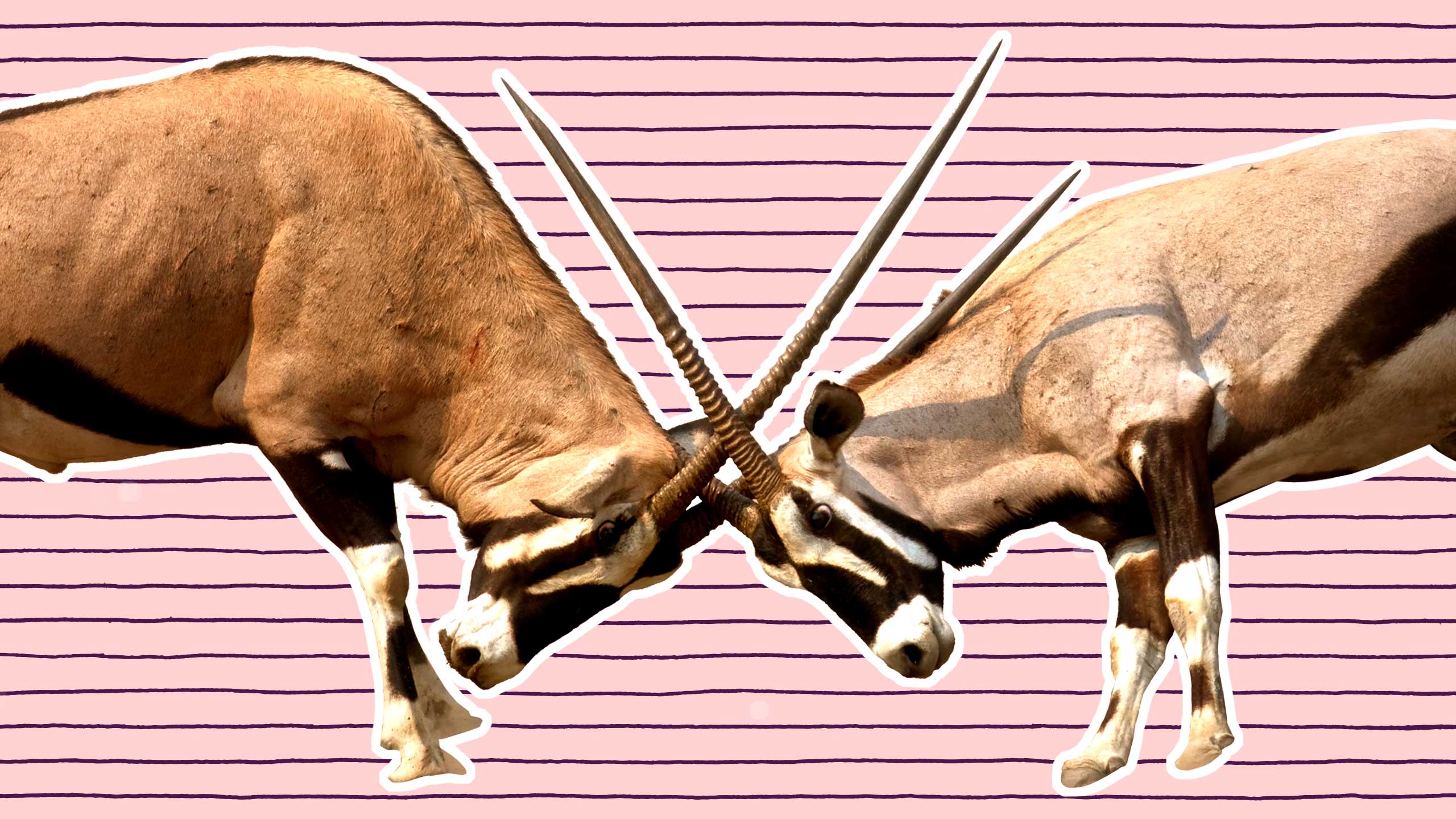

Abuse takes many definitions, depending on the context and whom you ask. I like the simple definition that Sarah Shulman uses in her much-debated book Conflict Is Not Abuse, which is that abuse is the use of “power over” someone in order to dominate them (as opposed to normative conflict, which Shulman defines as “power struggle”).

So going with that definition, we can identify interpersonal abuse as the misuse of power one person holds over another: A boss sexually harassing an employee, for example, is abuse. So is a landlord using the threat of eviction to extort tenants, or a straight teacher bullying a queer student. These are very clear examples of the misuse of power over someone.

Yet things get a bit fuzzier when we wade into the realm of intimate partnerships—or even friendships—between adults, because there are so many layers of power to parse. One partner might be racialized but wealthier, while the other is white and poor. One might be trans and abled while the other is cis and chronically ill. In any given relationship and at any given time, one person might be physically stronger or have more access to social networks, and so on. In contexts like these, the dynamics of power are fluid and constantly shifting. This means that we can’t always rely on simple identity markers or roles to tell us whether abuse is happening, or in what direction.

“Simply put: Abuse is about overriding the other person’s boundaries through force or manipulation.”

A deeper look at the dynamics of abuse will often reveal the presence of two important factors: Violent behaviours (or, actions that are intended to intimidate, control and/or create serious physical or psychological harm) and repetition. Through this lens, abuse is hurtful behaviour that is often repeated over a period of time. It is usually an attempt on the part of the abuser to get their emotional needs met by establishing either covert or explicit domination over the other person. Simply put: Abuse is about overriding the other person’s boundaries through force or manipulation.

Common patterns of abuse in intimate relationships include: Name calling and put-downs, intentionally making someone doubt their perceptions of reality (often called “gaslighting”) in order to control them, threats of violence, financial coercion (withholding or taking away money) and actual physical harm. Crossing digital boundaries such as breaking into a partner’s email or social media accounts in order to monitor their communication, or releasing compromising or embarrassing personal images without consent is also a common form of abuse. In an LGBTQ2S+ relationship, abuse may also take the form of using the threat of outing someone who is closeted in order to intimidate or manipulate them.

Let’s stop and do a quick self-assessment, Loud: In your relationship, do you feel that there is a consistent imbalance of power that gets taken advantage of? Does it feel difficult or impossible to have your boundaries respected? Are there acts of violence that create either physical harm or lasting emotional pain? If you or your partner answers “yes” or “maybe” to any of these questions, then that might be an indication that something concerning is going on.

On the other hand, if you both answered a firm “no” to all three, then it seems a lot less likely that there is an abusive dynamic in your relationship. Again, I don’t know you in real life, so if there’s ever any doubt in your mind or your partner’s, I’d advise seeing a professional!

It’s important for us to remember that healthy couples do, in fact, fight—and yes, even raise their voices at one another from time to time. Some couples are more passive-aggressive, while others are more explicit.

There are often cultural elements to this. For example, when I was growing up in my Chinese family, we didn’t fight all that often—but when we did, it was loud and direct. Direct confrontation is much more encouraged in some cultural contexts than others, and this can seem shocking or frightening to individuals who have been raised in environments where the direct expression of anger is discouraged. Additionally, the dominant white, middle-class culture tends to uphold the anger of some while stigmatizing the anger of others—that is, white men’s anger is often praised or at least tolerated, while racialized people and other marginalized communities are often heavily punished and stereotyped as “dangerous” for their anger. Yet there is enormous value to anger that is expressed in a healthy way.

In a healthy relationship, anger can be expressed in all kinds of ways—loudly, quietly, all at once or slowly over a period of time. What’s important is that the fight is fair: Neither partner should feel afraid for their safety or well-being. Put-downs, slurs and verbal attacks that are meant to shame and degrade should be avoided. In a fair fight, the anger is about a problem and not about a person, and that should feel more or less clear.

If you’re unsure about whether you’re fighting fair, or if you feel that things are starting to slide into a dangerous zone, then I’d suggest calling a time out and checking in later. One thing that tends to be helpful after a fight (and after the delicious make-up sex you refer to) is asking how things went for your partner. Did the fight feel fair to them? Are they okay with the raised voices? Some folks are extremely negatively affected by shouting, while others find it incredibly freeing to be able to let loose and yell around the people they trust. The key is to find a dynamic that works for both of you—and as long as that’s the case, then no one else’s opinion really matters.

As for your friend, Loud? I can certainly appreciate that she cares about you enough to want you to be safe. That’s a good quality to have in a friend. But this might be an opportunity to talk about where her concern comes from, and whether that’s rooted in your experience and values or in hers. Any good friendship has room for disagreement and expressions of concern. But at the end of the day, only you get to define your own experience.

If you love your relationship, Loud, and your partner does too, then I encourage you to trust that mutuality. Abuse and toxicity are often slippery words that can mean different things to different people. But we can trust the feelings that emerge from our relationships to tell us the truth. When our relationships feel nourishing and joyful, when we feel safe to be angry, when the good outweighs the bad—that is relationship health. When our relationships feel exhausting and confusing, when our anger is terrifying to ourselves or to our partners and there is more pain than joy, we know that something is not right. Trust your feelings, Loud. Trust yourself and the knowledge that healthy intimacy comes in infinite shapes and colours.

Kai Cheng Thom is no longer a registered or practicing mental health professional. The opinions expressed in this column are not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. All content in this column, including, but not limited to, all text, graphics, videos and images, is for general information purposes only. This column, its author, Xtra (including its parent and affiliated companies, as well as their directors, officers, employees, successors and assigns) and any guest authors are not responsible for the accuracy of the information contained in this column or the outcome of following any information provided directly or indirectly from it.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra