Leonardo da Vinci, one of history’s greatest artists and the definition of a Renaissance man, was an accused sodomite by 1476.

Homosexuality was endemic in his hometown of Florence; city council, in response, created a squad of officers of the night, preservers of morality. Da Vinci stood accused, along with three other men, of having sex with 17-year-old Jacopo Saltarelli. The charges were made anonymously and eventually were dropped, because the accuser never came forward with evidence.

Saltarelli may never have been his lover, but someone did come into da Vinci’s life during the summer of 1490. Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno was the son of a resident of da Vinci’s vineyard outside Milan. He was 10 years old when he joined the da Vinci household as a fattorino — an errand boy who worked for lodging.

Giorgio Vasari, a 16th-century Italian art historian, described Gian as a youth “most comely in grace and beauty, having fine locks, curling in ringlets, in which Leonardo greatly delighted.” Da Vinci and his household had a better description for him: salaì, Tuscan slang for devil, demon or unclean one.

The nickname quickly proved suitable to the child — da Vinci wrote in a letter to Salaì’s father that on the second day of his employment, da Vinci bought some clothes for his new errand boy, and “when I put aside some money to pay for these things he stole four lire, the money out of the purse, and I could never make him confess, though I was quite certain of the fact.”

Evidence continued to mount against Salaì during his career with da Vinci; it’s not surprising that his father might have wanted to send the boy away from home. He was a brat — da Vinci wrote of how at a dinner, “Salaì supped for two and did mischief for four, for he broke three cruets and spilled the wine” — and an incorrigible larcenist, constantly stealing from da Vinci and his fellow assistants.

Historian Ross King, in his biography Leonardo and the Last Supper, writes that not only did da Vinci keep Salaì in his household for years, he was constantly giving the boy gifts and clothing him in finery. King notes that in 1560, decades after da Vinci’s death, one artist wrote an imagined conversation between da Vinci and a Greek sculptor, where da Vinci reveals that he loved Salaì most deeply when the boy was 15, illustrating how speculation about their relationship continued long after they were gone. King points out that when Salaì was 15, da Vinci had just started The Last Supper in the Milanese convent.

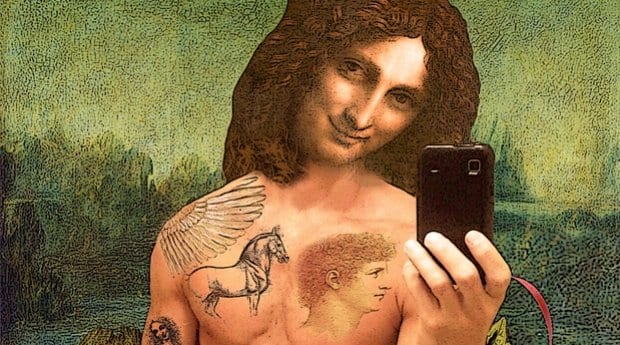

Indeed, Salaì was something of a muse to da Vinci. No official image of Salaì by his mentor exists, but a face crops up time and time again, most notably in da Vinci’s painting St John the Baptist. This bizarre, androgynous figure could very well be Salaì in his 30s — still working for da Vinci as an assistant and doing some minor painting of his own. Another sketch, now referred to as The Angel Incarnate, gives the same figure a breast and an erection, making it something of an early transsexual porno. If this figure is Salaì, da Vinci seems to have had an erotic transfixion with his model.

While Salaì continued his thieving ways, he was also a lifelong companion to da Vinci until the artist died in 1519. Mysteriously, while one younger assistant was the principal heir and executor of da Vinci’s estate, his will noted Salaì as only a servant but left him half the da Vinci vineyard, where Salaì had a house.

Salaì married in 1523, at the age of 43, though the marriage was short-lived. He died from a crossbow wound received in a duel. Even with all the information King brought together about Salaì in Leonardo and the Last Supper, I was saddened to learn that da Vinci’s lover and muse remains a marginal figure in the artist’s history. He may not be remembered as a great artist or even a great apprentice, but at least he has a place in history as a mischievous scamp who was nothing but trouble his whole life — da Vinci’s beloved, lifelong devil.

History Boys appears in every issue of Xtra.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra