To celebrate Xtra’s 20 years of publishing to Ottawa’s gay and lesbian community, we’re digging through our archives to reprint a selection of noteworthy stories that highlight our community’s rich history. “Charlotte loved Margaret” first appeared in Capital Xtra #66, Feb 19, 1999.

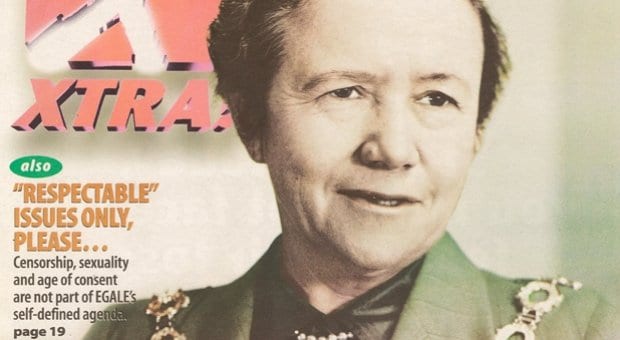

Last month, the National Archives of Canada opened the last and most eagerly awaited of Charlotte Whitton’s 134 boxes of personal papers, making the outspoken former mayor of Ottawa and child-welfare advocate once again the subject of controversy.

The box, which Whitton wished to remain closed until 1999, contains hundreds of letters written by Whitton over the course of two years to her housemate and long-time companion, Margaret Grier. Grier died in 1947.

The box contains a file folder filled with correspondence between the two women and letters to Grier that appear to be Whitton’s attempt to purge the guilt she felt for being absent when Grier died. Whitton was in Alberta, where she was facing libel charges because of her harsh criticisms of adoption policies in that province at the time. It is the nature of these letters that has sparked the controversy, for they reveal an intimate and loving relationship between the two women that spanned the course of 30 years.

Charlotte Whitton was an aggressive feminist to be sure, but was she also a lesbian?

There will never be a definite answer to this question, but a glance at her life and at her relationship with Grier may provide some clues. It’s important to remember that Whitton’s coming of age was at a time vastly different than the one we live in today — a time when women were expected to marry and never live alone. Those who did pursue a career over marriage faced a bleak and lonely future.

Whitton was often described as “mannish” and “unladylike” because of her masculine hairstyle and distaste for fashion. She explained away her short hair by saying it was “less trouble in the wind.” In school, she excelled at sports, especially field hockey and basketball. It was while she was studying at Queen’s University that she had her first and only romance with a man, by the name of Bill King. This “courting” was done mostly through correspondence, and it appears that King was rather more of a handsome and convenient escort for Whitton than a serious romantic relationship.

Whitton, who was fiercely independent, could not accept the role of wife and mother for herself but fully believed that a woman’s place was either in this traditional role or as a celibate activist for social welfare. She believed celibacy was the only route for an independent woman to achieve her goals, since it allowed a woman to focus all her energies on social work. One of her most important role models was Elizabeth Tudor, the virgin queen, who seemed to epitomize this attitude. Whitton’s parents had a strained marriage; there was a lot of tension in her family home, and this too could have influenced her decision not to marry.

Whitton also had a profound fear of dying in anonymity, which surely would have happened if she had opted for marriage. Whether or not she hid her lesbianism behind these ideals will never be known. An important factor to consider is that Whitton was also a devout Anglican, and to be a lesbian during her era would have been very traumatic for her. Also, as a woman who needed a paycheque, any risk of scandal would have been disastrous to her career.

As a feminist, Whitton believed in and fought for equal pay and equal opportunities for women in the public and private sector, although she did not believe in married women working outside of the home and held very conservative views on abortion and divorce. Her views on sexuality have been described as “prudish.”

Her relationship with Margaret Grier, however, indicates a kinder, gentler side of Charlotte Whitton.

The two women met in Toronto, where they were both residents at the Kappa Alpha Theta society house on the campus of the University of Toronto. Whitton accepted a position in 1918 as assistant secretary with the Social Service Council of Canada, and Grier worked with the juvenile court, the Big Sisters Association and the Girl Guides. In Grier, Whitton had found a soul mate, even though the two seemed to have very diverse natures. Grier is described as shy, fair and quiet, with delicate features and a calm spirit. Whitton, younger by four years, was considered intimidating, confrontational, ambitious and egotistical. Whatever their differences, the pairing was perfect for them. In 1922, they moved to Ottawa together in order to advance Whitton’s career in social work and to allow her to pursue her goals in government.

They set up house together and lived in a “Boston marriage” type of relationship, a term used in the late 19th century to describe a long-term monogamous relationship between two unmarried women, most likely feminists, who were financially independent of men either through inheritance or career. This arrangement was socially acceptable at the time, since women sometimes chose a career over marriage, or for whatever reasons found themselves “spinsters.” Living alone was neither socially acceptable nor financially possible.

The two women had many nicknames for each other, such as “Mardie,” “Putty,” “Pussy” and “Red Cat” in reference to Grier, while Whitton’s nicknames included “Lawrie,” “Charlie,” “Charles,” “Sharl,” “Lot” and “Rags.” Whitton often wrote poetry to Grier. A sample verse is sure to raise a few queer eyebrows, although it was not uncommon for single women of that era to romanticize their same-sex friendships:

So softly your tired head would lie

With gentle heaviness upon my breast

And knowing but each others’ arms

Desiring nothing more we two would rest

They also owned a cottage together, on McGregor Lake, and escaped many a humid Ottawa summer weekend there. One letter written by Grier to Whitton while she was away on business — which was often — seems to sum up the nature of their relationship: “Just two nights gone and I’m so lonesome I could cry whenever I stop to think for a minute — Oh Lawrie, dear, I’m just about crazy all the time you are away from me.”

In letters written to Grier after her death, Whitton bares her soul. She wrote flowery and romantic prose to Grier, such as in a letter written on Dec 31, 1947, her first letter to Grier after her death:

“Oh! Mardie, Mardie, Mardie, how can I go on? Ours wasn’t love, it was a knitting together of mind and spirit; it was something given to few of God.”

In another letter:

“Mardie, dear. Once again, just you and I together alone tonight veiled from my sight and withheld from my embraces.”

Whitton was also upset that Grier had burned a majority of the letters sent her prior to her death, an act that raises the question, why? Was Grier embarrassed or ashamed of the relationship or just a particularly fastidious housekeeper? There is also the question as to why Whitton requested the final box of papers sealed for 24 years after her death in 1975. Was she concerned that the contents would be misconstrued and point at a lesbian relationship? Did she think the late 1990s would be a more accepting time for the contents to be revealed? Or was it out of respect for the reputations of colleagues that she often criticized in her correspondence? Again, we’ll never know the real answers to these questions.

One thing is clear, however. Whatever the relationship between Charlotte Whitton and Margaret Grier, it was indeed one based on love, admiration, compatibility and respect. Grier’s death was a severe blow to Whitton, and aroused in her profound feelings of loneliness and regret. Whitton felt a strong need to keep Grier as close to her as possible in the years following her death.

From the letters, it appears that Grier’s memory gave Whitton the strength she needed to become a political force in a man’s world — a force we remember — who caused more than one man to curse in exasperation, “That damn woman!”

Was it lesbian love?

Was former Ottawa mayor and child welfare advocate Charlotte Whitton a lesbian?

The question was the basis of an Ottawa Citizen story last month featuring newly released personal letters from Whitton to her long-time “companion,” Margaret Grier.

“The bottom line is that we don’t know for sure,” says Barbara Freeman, who covered Whitton’s funeral in 1975 for CBC Radio.

“We do know that they had an extremely passionate relationship that certainly could be called emotionally lesbian, whether or not they actually had sex,” says Freeman, a lesbian scholar and now associate professor of journalism at Carleton University. “When she was alive, people might have suspected that she was a little queer.”

Freeman says the debate generated by the Citizen story shows how people are labelled. “People aren’t ready to call [Whitton] a lesbian unless they know [Whitton and Grier] had sex together.”

“People are still assuming that the labels belong with sexual activity, whereas there are lots of people who are celibate who are also gay. Whether or not she got it on with this woman has absolutely nothing to do with whether or not she was a lesbian,” Freeman says.

Queer historian Steven Maynard is familiar with the kind of debate surrounding the Whitton identity. “These are debates that have been playing within lesbian historiography for a long time,” he says. “It’s a fairly central debate about whether there has to be evidence of sexual relations between two women in the past to qualify them as belonging to lesbian history, or do we also include that whole other gamut or range of — sometimes fairly intense — emotional relationships between two women without evidence of sexual relations?”

Maynard cautions that it isn’t a yes or no answer. “Yes, we should claim her for lesbian history, but let’s be careful about it. Let’s not be uncritical. She had some fairly contradictory political impulses — quite a few of them.”

While Whitton is known for her efforts as a child-welfare advocate, at a time before the development of social work, she fell behind contemporary social values, says Norman Dahl.

“She got out of step with child welfare and the social welfare movement because she was a very conservative person. She thought communities should look after their own, whereas we [in the 1950s and ’60s] were moving into a whole new philosophy of government social programs,” he says.

Dahl worked as an information officer for the Canadian Council on Social Development, the descendant of the agency Whitton led between 1922 and 1941. “I’m 70 years old, and there are not many of us left who remember her legacy as a very important person in the field of child welfare,” says Dalh, who has lived in the Ottawa area with his lover, George Wilkes, since the 1950s.

Dahl believes Whitton wanted to come out posthumously. “She wanted us to know all about this. I think it was a very beautiful thing to do. She wanted us to know, and it was very important to her.”

Dahl says it was important to Whitton that her letters become public given that — at the time — Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government was decriminalizing gay sex. “When she was living with Marty [Grier] all those years, we were still illegal. You couldn’t talk about being gay in those days, certainly not [as] a public figure.”

Was Whitton’s relationship to Grier sexual?

“She exuded energy and she looked like a very well-put-together person and, I think, very fulfilled at home, but you don’t know,” he says. “What’s wrong with thinking that this was a physical relationship? If it was, fine. If it wasn’t, it’s really none of our damn business,” he says. “I like to think it was.”

“She was a beautiful writer,” he says. “The woman had a real command of the language.”

“For goodness sake, I think the warmth of those letters is quite clear,” he says. “I like to think she had a wonderful relationship.” —Philip Hannan

To celebrate Xtra’s 20 years of publishing to Ottawa’s gay and lesbian community, we’re digging through our archives to reprint a selection of noteworthy stories that highlight our community’s rich history. “Charlotte Loved Margaret” first appeared in Capital Xtra #66, Feb 19, 1999.

Read “Marching Forward: (The First) 25 Years of Lesbian and Gay Activism in Ottawa”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra