Imagine a trans woman in love.

She’s been going on dates with someone. She and this person have shared intimate moments, building trust and connection as they hold hands in public and say things to each other that they’ve never said to anyone else before. They’ve shared tentative kisses and furtive embraces. She’s slept in his arms and trusts him with her life.

Now she’s undressing before him, revealing her body with tentative hands.

The body she reveals has been scorned by the world and invaded by a surgeon’s scalpel. Her body has been examined and judged by everyone she’s met. She’s bled through her sheets and stained the mattress while healing. More than once, she’s bled through her jeans.

She’s spent years loving and hiding her body, both hating and celebrating it as she undergoes hormones and surgery to reveal its true form. Now she’s exposing it to someone she hopes will love it as much as she does. She trusts in her love and the possibility of being loved back.

This is the pain I want to talk about. The vulnerability of her body meeting someone else’s gaze in a dimly lit room. The fear and ache on her face, her fingers unbuttoning jeans and slipping panties off. The light falling across her soft skin as she takes a deep breath before the last of her defenses drops to a pile on the floor.

His eyes change from their familiar warmth to a coldness she’s never seen before. He looks downward for a moment. When he meets her gaze again, there’s a look of shame and sorrow in his face that will haunt her for the rest of her life. Then he rises and leaves the room.

She stands there, alone and naked. If she could die, she would. But she doesn’t. She keeps on living.

And it hurts more than anything she’s ever known.

This a pain which is rarely talked about and almost never witnessed.

“There are almost no film representations of trans women in love.”

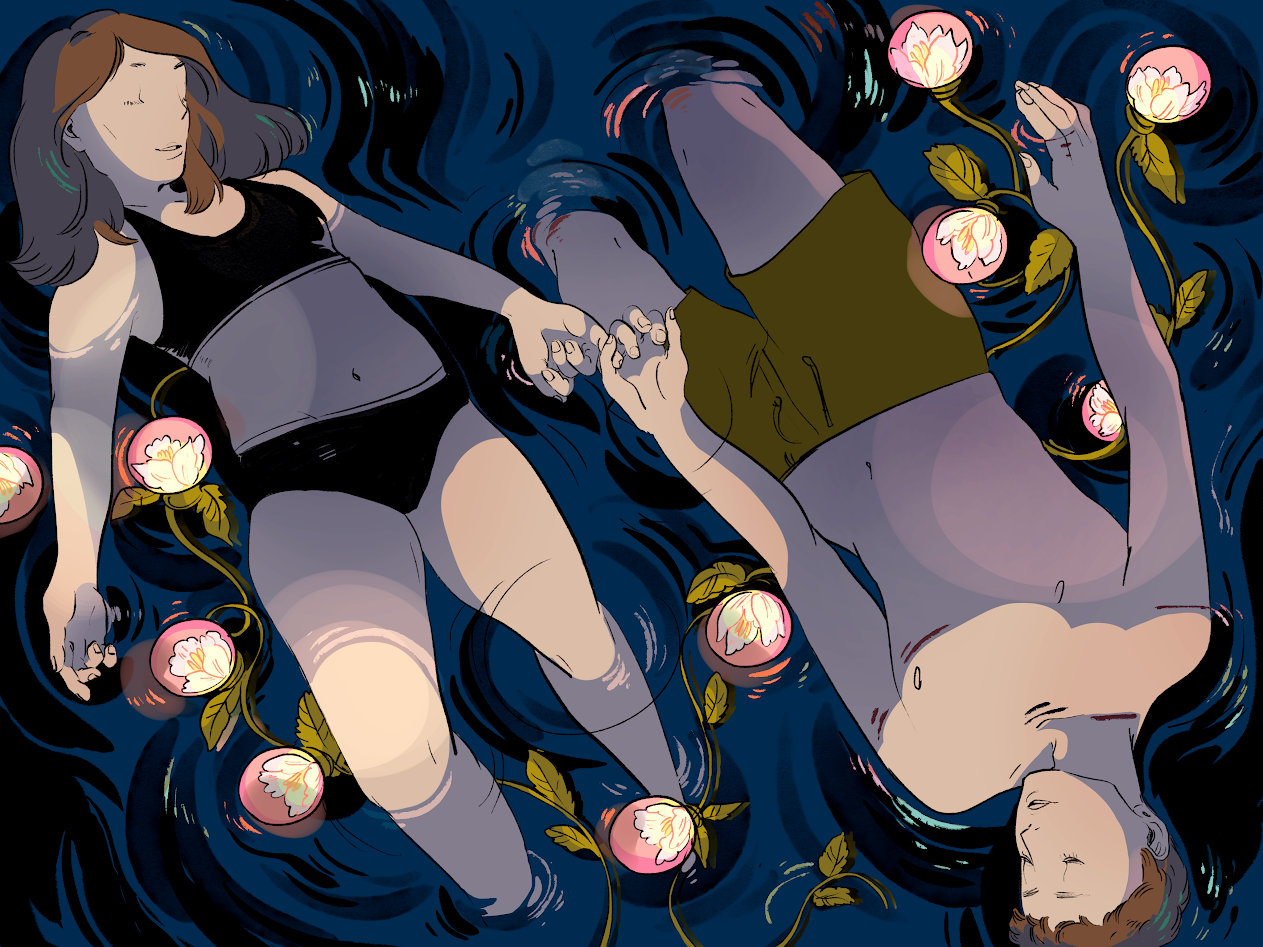

There are moments in life which hurt so much that the body can’t hold them. The pain surrounds the body like water, immersing you until every part of your skin aches. No matter what you do, you can’t escape the hurt. It rests on the surface of your life, refusing to evaporate, lapping at the edges of your mind until there is nothing left to do but surrender.

As a transsexual woman, I’ve lived through great pains. I had two surgeries last year, one to change my face and another to change my genitals. I’ve been assaulted on the street, an attack so violent that it shattered my glasses and left me with a concussion I’ve been misgendered and cat-called. I’ve heard the word “tranny” more times than I can count. I was raped.

Shockingly, those pains recede. My body has healed through them, bearing the burden and rising upwards back into life. Out of the many pains I’ve lived through, the pain of confronting my partner’s transphobia still blisters inside me. It is relentless. I think it will kill me eventually, a final release from hurting that I crave and fear in equal measure.

If I had to name this pain, I would call it “vulnerability,” but that word doesn’t capture the complexity of its capacity to wound. It is a pain that grows where the intersection of transphobia and intimacy meet, but it isn’t easy to put into words. And until I watched the films Different for Girls and Boy Meets Girl — the former film about a trans woman who reunites with a childhood friend and the latter a romantic comedy about a trans woman in love — I’d never seen this pain represented in media before.

“I was struck at how different it felt to watch a girl like me fall in love, have sex and break her heart.”

There are very few film representations of trans women in love. Trans women regularly appear as villains, victims and vixens in television and film, but rarely as fully fleshed out girls with desires and romance. When I watched Boy Meets Girl, a 2014 romantic comedy with a trans actress as the romantic lead, I was struck at how different it felt to watch a girl like me fall in love, have sex and have her heart broken. It wasn’t the wondrous escapism I’ve come to associate with romantic comedies, but a sudden searing pain at seeing my life on screen in living colour.

Boy Meets Girl isn’t a perfect movie. The acting is good, but it’s low-budget and the plot lines don’t fully mesh. It’s almost entirely white. Despite these obstacles, the movie manages to speak directly to the complexity of trans girls in love: Ricky, the trans girl protagonist, lives in a small town in the American South. She’s had nothing more than a close friendship with her straight cisgender guy best friend, Robby, until a new cisgender girl, Francesca, enters the picture.

Ricky and Francesca end up having a brief romance, a positive portrayal of bisexual trans women which is deeply lacking in other films. Ricky and Francesca’s relationship matters to me because I’m also a trans girl who unexpectedly fell in love with another woman. Their romance drives Robby to finally admit his attraction and love for Ricky, a cinematic climax that ends with Robby revealing his internalized transphobia by suggesting that Ricky is still “like a guy.”

When Ricky cries in response to Robby misgendering her — she tells him that out of everyone in the world, she trusted that he saw her for who she really is — her pain in this exchange is important. While it’s easy to think that her pain is simply about romantic or sexual rejection, the truth is that Ricky’s hurt is so deep she trusted Robby. Being a trans girl means navigating the transphobia of cisgender people constantly. Trusting them enough to become their friends is hard enough, but trusting them enough to share your body with them requires a faith that few cisgender people recognize or deserve.

In the final dramatic confrontation between Ricky and Robby, she exposes her naked body. Ricky has run away from home, considering suicide after their fight. When Robby finds her swimming at night in a lake, Ricky steps out of the water to confront him, challenging him to prove that he sees her for who she is as she is. After his transphobia, Ricky’s reveal of her self is as fearless as it is vulnerable.

It’s the first time that I’ve ever seen one of my most painful experiences of sex and intimacy with cisgender men represented in a film.

“Their love story isn’t an escape from my body, but a return to it.”

The film shows Ricky’s naked body as she stands in the cold night air. Her body is what my body once was pre-operation, with wide shoulders, small breasts and a penis. Robby stares at her body for a moment before stepping forward to embrace her in a passionate kiss. It’s a moment where her vulnerability as a trans girl in love is met with his desire and care for her.

Unlike the romantic comedies I grew up with, their love story isn’t an escape from my body, but a return to it.

I’ve been Ricky so many times in my life. Partners have asked me what my post-operation vagina looked like and demanded to see it as proof of my womanhood. Partners have told me that they tried to be open but couldn’t love a girl like me. They’ve seen my vulnerability and disappeared into themselves: disgusted, angry, or simply saddened. Transphobia fills the space between my body and theirs, an unspoken discomfort and shame that I can never be real enough to reach across.

I can’t explain how small I’ve felt in those moments before those boys. My body disappeared into itself, my hands shaking.

Boy Meets Girl manages to capture that intense feeling of fear and fragility perfectly through Ricky’s defiant rise out of the water. In that scene, Robby doesn’t look disgusted or ashamed. Instead, he offers Ricky something that very few partners have ever offered me: gentleness and love.

“A trans girl in love being loved back is what I need to see to keep living.”

As the movie ends, they drive off to New York together, a cisgender boy and a trans girl in love without any shame at all between them. It’s an everyday love which very few trans girls will ever get.

Boy Meets Girl shows a possibility for trans love that is rarely realized, but I’m happy that the possibility exists in cinematic detail. Representation matters because it creates imperfect mirrors for us to imagine our lives. I see myself and my pain in Ricky. Seeing ourselves in media and art is crucial to imagining our possibilities, but what we see ourselves doing matters as much as the images of us on the screen. A trans girl in love being loved back is what I need to see to keep living.

In a landscape filled with films of cisgender women falling in love, there is one movie where a cisgender boy overcomes his transphobia to love a trans girl back. Even if their romantic ending feels impossible to me, their existence provides a chance to imagine a different life for myself.

Sometimes healing doesn’t come from the circumstances of your life changing, but from finding new ways to return to hope.

I want to hold onto hope like my lover used to hold me — tight underneath warm blankets while I collapsed, as small as I could against his chest, falling asleep inside a love I never wanted to end.

“I want to hold onto hope like my lover used to hold me.”

I rewatched Boy Meets Girl before writing this essay. When I got to this scene, I stopped the movie and cried in the emptiness of my apartment. I rarely cry anymore, but it felt right to acknowledge the pain that I still feel. I cried until I wasn’t crying, but hurting, soundless and hunched over in my bed like an animal. Something tore open again inside me.

It felt like when my parents abandoned me in a hospital after I came out to them. It hurt more than the gruelling pain in my lower body when I was hospitalized after my sexual reassignment surgery for complications. I felt as if my body was being torn apart from inside, as if I was a single hurting cell. It lasted for five minutes before disappearing back into my spine where it lives.

I turned the movie back on. Ricky and Robby wake up in bed together, drinking coffee and idly holding each other as the sun rises. I remember what my lover’s hand in mine felt like, a ghostly memory that evaporates as soundlessly as my screaming. His transphobia still hurts me so much — not because it didn’t work out between us, but because I know that the person I trusted and loved for two years never saw me for who I am.

After everything we shared, he still looked at me and saw someone to be ashamed of. Nothing heals that pain, but I live through it. And like Ricky, I still lift out of the water, fearless and naked before my lovers, daring them to love a girl like me.

Author’s note: I want to explicitly acknowledge that trans women have a wide range of experiences and embodiments. My story is personal one. Other trans women/trans feminine people may have differing experiences and may use different language to speak about their bodies. It’s important to understand that trans people have a wide range of romantic, sexual and embodied experiences — all of which are valid and deserve to be represented.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra