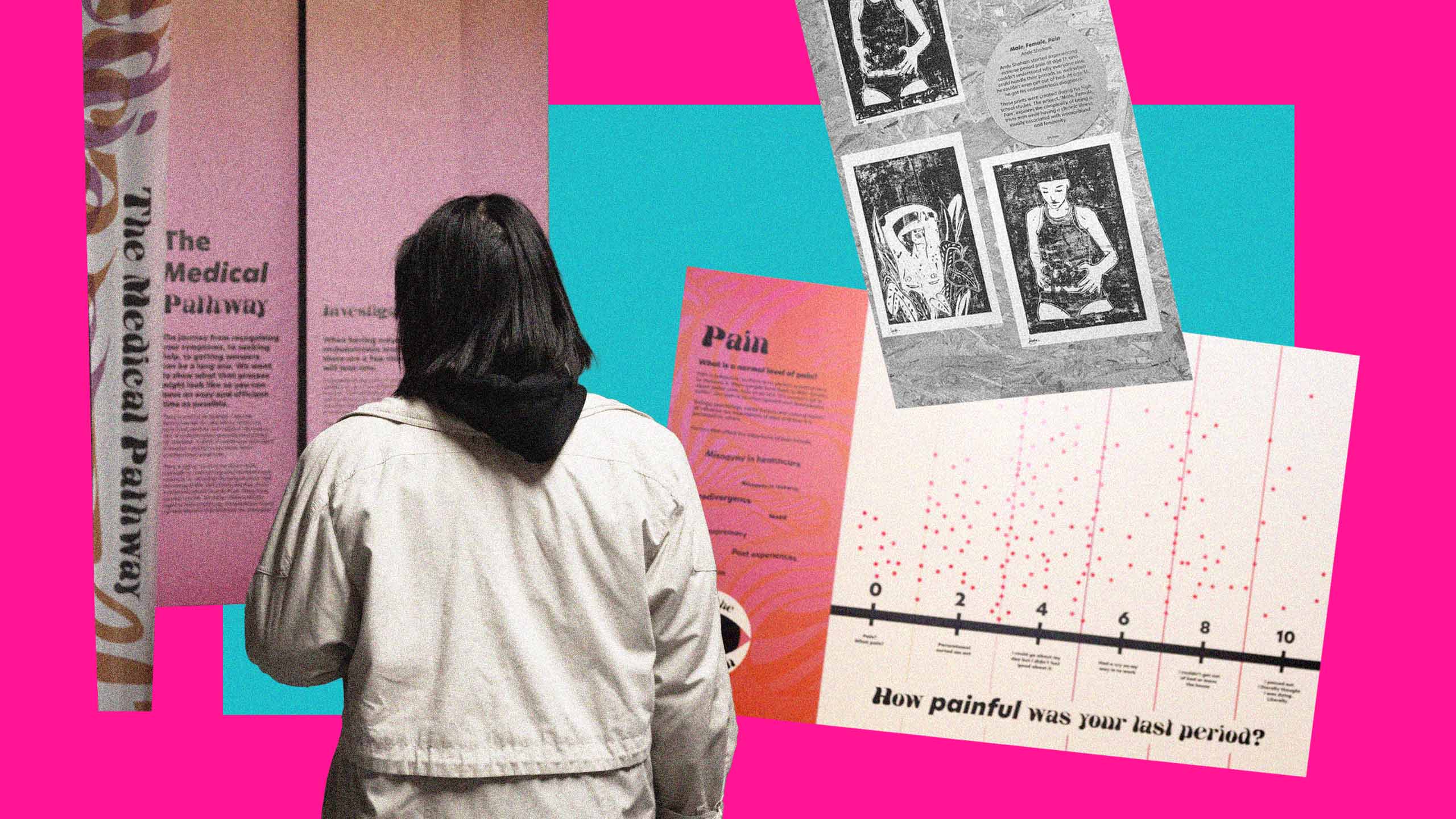

The world’s first brick-and-mortar museum dedicated to vaginas, vulvas and the gynae anatomy reopened last Saturday after being forced to close down in January. The first temporary exhibit at their new, long-term premises in Bethnal Green is Endometriosis: Into the Unknown. The exhibit aims to take visitors to the museum on a journey from the basics of endometriosis to the cutting edge of research, exploring myths, as well as the reality of living with the condition—all while remaining inclusive of trans and non-binary folks.

The Vagina Museum was forced to close its doors to the public this year. In Spring 2023, the Vagina Museum launched a major crowdfunding appeal in order to be able to secure new premises.

The Vagina Museum’s founder and director, Florence Schechter, said in a press release about the newest exhibit: “Raising awareness of endometriosis has been a common request from our community since the Vagina Museum project began.”

That may be because endometriosis is widespread (190 million people have the condition worldwide), but awareness of it is low, even among healthcare providers. For trans and non-binary people, there’s an additional hurdle to diagnosis and treatment because endometriosis is seen as a “women’s health condition.” It’s rare to find information that acknowledges the existence of trans and non-binary people with endometriosis, let alone an exhibit like the Vagina Museum’s, which actively seeks out and includes their voices.

Trans and non-binary people are frustrated that resources on endometriosis are so often heavily gendered (and pink). Lo Shearing, who is 28 and gender-fluid, got an endometriosis diagnosis after a laparoscopy during their surgery to remove an eight-by-eight-centimetre tumour from their right ovary a few years after symptoms of their endometriosis started. When they were researching the condition, they came across a website that referred to an endometrioma (the medical name for tumours caused by endometriosis) as a “female tumour.”

“How can a tumour have a gender?” they say. “My tumour isn’t female, my tumour isn’t male. It’s a sack of blood.”

Shearing added that many of the existent resources for endometriosis are focused on protecting your fertility. “Whether or not I’m fertile is the least of my worries compared to my actual health and the pain that I’m in every day.” When they needed surgery to remove their tumour, their doctors were focused on removing it in a way that would protect their ovary and their fertility, despite Shearing explaining that they didn’t care about that. They felt the assumption was that “the only reason you’d care about your reproductive health is so you can get pregnant, as opposed to seeing women or people with uteruses as full people.”

Shearing isn’t alone in finding this language alienating. Dami Fawehinmi, 24, says that when they were diagnosed, they really needed to hear that endometriosis wasn’t just a concern for cis women. They wish language like “people with endometriosis” was more common, and are working on speaking up for themselves in medical settings: “I know my identity and existence are important, and most importantly, deserves to be respected. Creating an environment in which your patients can tell you about themselves is so so important. It’s your life and your health.”

Gendered, trans-exclusionary language has a real-world impact on trans people. Endometriosis causes life-changing symptoms, including chronic pain and fertility difficulties. For trans and non-binary people, accessing resources and support often requires engaging with services that misgender them and cause dysphoria.

“The exhibit is proof that resources around endometriosis can be medically accurate while still being inclusive.”

Hoping to provide a more inclusive set of resources, the Vagina Museum produced Endometriosis: Into the Unknown in collaboration with Oxford EndoCaRe, part of the Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics based at the University of Oxford. The exhibit is proof that resources around endometriosis can be medically accurate while still being inclusive of trans and non-binary people. Fawehinmi says that more inclusive language—like that used in the exhibit—makes them feel seen. Language that includes rather than alienates them helps them feel like they, and other people with endometriosis, will be able get the help they deserve.

Ensuring that people who aren’t cis women are included in conversations about endometriosis isn’t only about trans-inclusivity. The condition doesn’t only affect women—or even just people with uteruses and ovaries. While it’s uncommon, people with penises and intersex people can also get endometriosis. A paper in the Avicenna Journal of Medicine in 2014 detailing “a rare case of abdominal pain” in a 52-year-old man explains that only a few cases of endometriosis in cis men have been reported. (That small handful now include that patient, who had a cystic mass found during an exploratory laparotomy that was “consistent with endometriosis.”)

Resources and conversations that acknowledge that endometriosis affects more people than just cis women are the first step toward ensuring that others don’t have to experience the same horrific dysphoria Shearing and Fawehinmi did while trying to get treatment.

Fawehinmi found support groups online, and benefited especially from spaces for Black and trans people with endometriosis that offered them help and community. It meant a lot to them to see people like them who understand and share their experiences—and that’s what the Vagina Museum’s endometriosis exhibit aims to do. Schechter says that the Vagina Museum has staff and volunteers who have endometriosis themselves. “They deserve to have information as well, and if you don’t do it in an inclusive way, that’s going to exclude them, then they’re not going to get the help that they need.”

The museum’s exhibit might not be able to directly change healthcare policy, but with anti-LGBTQ2S laws sweeping across the U.K., Canada and the rest of the world, inclusive information about conditions like endometriosis is increasingly hard to find. Shearing says many community groups for people with endometriosis are transphobic and “use the trauma of having endometriosis to attack trans women and gender-variant people.” An in-person exhibit that cannot be censored by social media is a reminder to trans and non-binary people that their stories are worthy of being told and their pain is valid.

While some critics have tried to posit that trans-inclusive health resources erase women, Shearing rejects the premise. Using gender-inclusive language when talking about conditions like endometriosis doesn’t erase anyone, they say, and “anyone who says otherwise cares more about policing the idea of womanhood than they do about treating people with endometriosis.”

Thankfully, there are tons of people who agree. The Vagina Museum has received positive feedback from trans and non-binary people over the years about the work they’ve done to ensure their exhibits and space are inclusive. Schechter explains that they’ve had people come in person, write feedback forms and send messages to their website and social media, expressing their relief at the museum’s trans-inclusivity. “They’ve often said it’s so wonderful to be able to get access to this information without feeling excluded or feeling triggered,” Schechter says.

The Vagina Museum’s commitment to trans-inclusivity shouldn’t be so notable. Their work stands out as one of the few exceptions to the rule that trans people should face discrimination and dysphoria when talking about health conditions that are typically seen as gendered. Schechter says, “Trans and non-binary people exist; that’s why they should be included. I think the argument shouldn’t be any more complicated than that.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra