A Christian nationalist movement that proliferated with last year’s Freedom Convoy appears to be steering anti-LGBTQ2S+ actions across Canada.

Toronto-based biblical scholar Christine Mitchell, who wrote in The Conversation about the convoy’s use of Christian nationalist slogans last year, and who studies and teaches the Bible through a modern feminist and gender studies lens, tells Xtra the rhetoric has escalated into “the language of genocide” as it’s shifted to target LGBTQ2S+ communities and specifically to dehumanize trans folks.

“It’s not a big leap,” Mitchell says. “It has to do with notions of self-identity. So if my identity is tied up in a particular kind of exclusionary way, and it’s really important to me, then people who threaten that—or are perceived by me to threaten that—become dangerous. They become something that has to be shut down.”

Mitchell, an academic dean and professor of the Hebrew Bible at the University of Toronto, says the movement is a radicalization of Christianity that combines Canadian nationalism with American-style white evangelicalism. She says nationalism and Christianity were closely connected in early 20th-century Canada, but began to “decouple” after the Second World War as the country embraced immigration, multiculturalism and secularism. “What we see now is people wanting to recouple Christianity, but in very particular forms of it.”

This kind of rhetoric is used more openly in the U.S., where emails leaked in March revealed anti-trans lobbyists and lawmakers believe they are engaged in a “holy war.” Mitchell says talking about religion publicly is more taboo in Canada, which adds an element of danger that can allow movements like these to fester in hiding.

“What we see is a profound fear about loss of privilege, basically and a zero-sum game—that rights and privileges are like a pie, and if somebody gets a bigger piece, that means I get a smaller one,” Mitchell says. “If that’s how you look at what it is to be in a society together, then I get that that’s scary. But when you tie in the Christian nationalism piece to it, what you’re saying is ‘Only certain people are fully human or fully Canadian. And I get to define what that is, based on my or my group’s particular interpretations of Christianity.’”

Mitchell started tracking the rising tide of Christian nationalism in Canada after she saw a banner at the February 2022 Ottawa convoy protest bearing the verse 7:14 from the New King James Version of 2 Chronicles, in which God warns Solomon that if his commandments aren’t followed, his temple will be destroyed and the people expelled. “If My people who are called by My name will humble themselves, and pray and seek My face, and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin and heal their land,” the verse reads. Mitchell wrote that this same text is often invoked by American evangelicals to support their claim of being responsible for “morally or spiritually healing their country.” The Freedom Convoy organizers also used Christian references in its press releases at the time, and raised money through Christian crowdfunding site GiveSendGo.

This year, many convoy-affiliated groups have shifted their attention to protesting drag shows and school inclusivity policies.

Action4Canada, a group that was heavily involved in the convoy and has since planned anti-drag protests and harassed school boards across B.C. over Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) guidelines, says its mission is to “protect Canada’s rich heritage, which is founded on Judeo-Christian biblical principles.” Its founder, Tanya Gaw, has said of SOGI guidelines that she believes “we’re in a spiritual battle of good versus evil.”

“Canada was founded on God’s word, the Bible,” an Action4Canada follower said during a school board meeting in Kelowna, B.C. in February in protest of inclusivity policies, before reading the Bible passage Mark 9:42, which says, “It would be better for him if a millstone were hung around his neck and he were cast into the sea than that he should cause one of these little ones to sin.”

Hazel Woodrow, education facilitator with the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, says this is a common passage used by Christian nationalists.

“I think it’s insinuating that there are people within this building who are causing children to stumble, who are who are messing with kids, and it would be better if they were drowned. So I think that’s quite a violent thing to say,” she says.

“If they’re saying that what they believe the Bible says should determine what is allowed in our society, that’s the definition of Christian nationalism.”

Woodrow says Canada was founded on Christian nationalism, which provided the basis for the violent assimilation and religious conversion policies targeting Indigenous Peoples. She notes that remnants of Christianity are still baked into our political structure—for example, prayers before city council meetings and crucifixes in political buildings—which gives some followers a feeling of entitlement, and, in their minds, legitimizes their claims of Canada being a Christian nation.

She says Stephen Harper’s conservative government pushed Christian nationalism in its last few years in office, and the movement has been bubbling up since. Harper took office in 2006, the year after the legalization of gay marriage brought Canada’s Christian right back into the media spotlight. Influenced by evangelical contemporaries Preston Manning and Stockwell Day, Harper brought in Darrel Reid, the former leader of Christian evangelical organization Focus on the Family Canada, as his deputy chief of staff, and Paul Wilson, who set up a branch of Trinity Western University to train young Christians for jobs in politics, as policy director.

Investigative journalist Marci McDonald’s 2010 book The Armageddon Factor: The Rise of Christian Nationalism in Canada warned that Christian nationalists were infiltrating federal government offices at the time. “In the five years since the prospect of same-sex marriage propelled evangelicals into political action, it has spawned a coalition of advocacy groups, think tanks and youth lobbies that have changed the national debate,” McDonald writes, adding these groups were “organizing with a vengeance that will not be easily reversed.”

McDonald wrote that skeptics at the time dismissed her concerns about an influential religious right taking hold in Canada, but she argued the American movement had more than three decades to flourish, and “by the time scholars and the mainstream media noticed, it had already infiltrated nearly every level of government from school boards to the Senate, often by stealth.”

The Christian nationalist movement gained followers and visibility during the pandemic, in part because some Christians were upset that COVID-19 rules restricted them from gathering to pray and worship the way they normally would. Woodrow says Christian nationalism is also tied to “petro patriotism,” which supports extractive resource development, sometimes on theological grounds—essentially believing God created the world for humans and it is therefore justifiable to harm the environment or other species for our benefit. This also helps explain the through-line from the Yellow Vest movement—a series of pro-oil, anti-carbon tax protests with far-right, xenophobic elements that started in 2018—and the succeeding Freedom Convoy.

“Overall, in terms of the organizers and the people who had the loudest voices in and around the convoy, I think it’s fair to say that their somewhat new cause du jour is the anti-trans and anti-drag and anti-queer stuff,” Woodrow says.

The groups peddling Christian nationalist and anti-LGBTQ2S+ rhetoric in Canada are numerous.

Liberty Coalition Canada, a group that formed in 2021 in opposition to public health measures and galvanized support from churches across the country, trained anti-LGBTQ2S+ school board candidates in Ontario, B.C. and Manitoba’s 2022 fall elections. The group has claimed its ultimate goal is “the most powerful political disruption in Canadian history,” according to CBC, and launched a sermon initiative in January called “Biblical Sexuality Sundays,” writing “The truth is that God has designed both men and women as well as marriage itself, and His design has been true since the beginning of time.”

Trinity Bible Chapel in Waterloo, Ontario, is among the fundamentalist Christian churches that gained influence after opposing pandemic restrictions. CBC reported this month that Pastor Jacob Reaume, referring to a trans student who recently died by suicide, used an anti-trans slur in a sermon and said, “If you’re going to live a lie to the point where you’re willing to mutilate your own body, it’s going to send you into dark despair.”

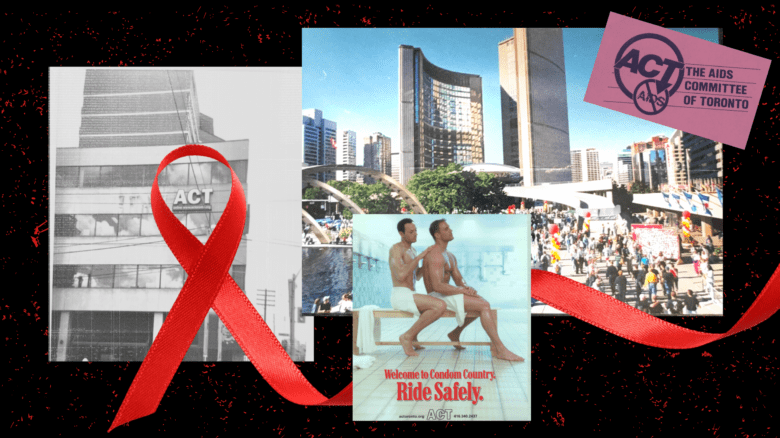

Campaign Life Coalition, which uses Bible verses to justify its stance on banning abortion and opposing LGBTQ2S+ rights, also promoted anti-LGBTQ2S+ election candidates last year. Stand4THEE, an anti-vaccine group that has consistently protested drag events, writes in its mandate, “First and most importantly we believe that rights are natural and God-given.” ACT! For Canada, another group that vocally opposes trans rights, promotes Christian literature and claims in its mandate to defend Canadian people “against all enemies, foreign and domestic who … seek to undermine the freedoms, economic prosperity, traditional values and heritage of the Canadian nation and peoples.” The Revival Reformation Alliance has held evangelical-style events dubbed “Battle for Canada,” weaving the language of militant Christianity and patriotism with diatribes against abortion and LGBTQ2S+ rights. Woodrow says Canadian Catholic publication LifeSiteNews also openly advocates for Christian nationalism.

In Alberta, Elliot McDavid, who organized last year’s Slow Roll Freedom Convoy and publicly harassed Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland in a widely circulated video that prompted a police investigation, and helped shut down a drag event in Grande Prairie in January. On Facebook, McDavid has posted, “There is only one law “gods law” [sic].” Take Back Alberta, a group that took credit for ousting former premier Jason Kenney in favour of Danielle Smith, and claims to control half the governing United Conservative Party’s board, has also invoked Christian nationalism. Vince Byfield, an Alberta separatist and regional captain with the group, told a Christian podcast that the movement to take over the UCP was “a sign from God” and “I knew that what was happening must be God-driven.”

“Language to watch for often revolves around purity, or the idea that the touching of the ‘sacred’ by that which is perceived as not sacred—such as people who identify as LGBTQ2S+—might ‘contaminate’ the sacred and make it ‘not holy.’”

Calgary Protestant preacher-turned-politician Artur Pawlowski, who was convicted of mischief for his role in the Freedom Convoy and got Premier Danielle Smith in hot water over a phone call in which the two of them discussed amnesty for breaking COVID-19 restrictions, has consistently expressed anti-LGBTQ2S+ views. In 2013, he said Calgary’s floods were caused in part by God taking vengeance on LGBTQ2S+ Albertans. In a speech this May, he said, “I pray, Father, that you will give us Florida’s politics,” before launching into a tirade about abortion, pedophilia and grooming, and saying “We’ll hunt you down,” seemingly in reference to LGBTQ2S+ Albertans and others who disagree with his views. He also called the media “devils” in a recent press conference.

The language is not always so obvious. Mitchell says much of the popular Christian nationalist rhetoric uses “code for God language,” because explicitly referencing God or the Bible can turn people off, especially in Canada. Language to watch for often revolves around purity, or the idea that the touching of the “sacred” by that which is perceived as not sacred—such as people who identify as LGBTQ2S+—might “contaminate” the sacred and make it “not holy.”

The commonly used term “grooming” implies “groomers” are preparing their victims to cross the boundaries of what is sacred. People will often invoke the words “natural” and “unnatural” to similar effect. In the early 20th century, Mitchell says, they would say it is “not natural” for women to have the vote, because there are “certain ways that are ordained.”

Similar language was invoked during debates around gay rights and gay marriage, and is now being used to call transition and trans identities “unnatural.”

“That’s the language of genocide,” Mitchell says. “And that is almost always grounded in this idea of purity, which doesn’t have to be religious, but it usually is.”

Woodrow says “parents’ rights” is another dog whistle used by Christian nationalists, informed by the theological belief that only parents have authority over their children. Words like “elites” and “globalists” can likewise be co-opted as dog whistles for the idea that Jewish people secretly control the world.

Mitchell says educating the converts and “true believers” is not going to make a difference. Instead, “It’s reaching the people who might get converted, and reaching them ahead of time.”

Sophie Bjork-James, an anthropologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, who studies white nationalism, evangelicalism and reproductive politics, says Christian nationalists have used language around “saving” children as moral cover since the 1970s, when Anita Bryant founded the first anti-queer rights organization in the U.S., called Save Our Children. Today, people use language like “chemically castrating” or “mutilating children” to reframe gender-affirming care as an assault on kids. Meanwhile, real dangers to children often lie within the groups purporting to be saving them. A recent investigation uncovered systemic child sexual abuse in the Southern Baptist Convention, the second-largest Christian denomination in the U.S.

Bjork-James says social media siloing has made it easier to dehumanize entire groups of people, which has added to the danger of framing LGBTQ2S+ people as evil in the current age.

“There are definitely many people, many policymakers, many individuals, [whose goal is] to not allow for there to be LGBTQ2S+ people in public life,” she says. “That is very dangerous.”

U.S. Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has proposed a nationwide ban on gender-affirming care for all trans people and legislation to declare there are only two genders that are assigned at birth, among other extreme anti-trans measures. Trump did an interview with Christian nationalist Gene Bailey on The Victory Channel on April 24, in which he promised to politically empower religious leaders if re-elected. The Guardian reported that an organization called Pastors for Trump, which is campaigning in swing states, has come under fire from mainstream Christian leaders for extremism, distorting Christian teachings and endangering democracy by “fuelling the spread of Christian nationalism.”

Bjork-James says the movement against LGBTQ2S+ rights has united Christian nationalists with other groups that came into the far-right during the pandemic through shared opposition to masking and social distancing mandates. The recent loss of abortion rights with the overturning of Roe v. Wade in the U.S. has now put their target squarely on LGBTQ2S+ communities.

“The twin issues mobilizing the religious right for the past 40 years have been opposing abortion and opposing LGBTQ2S+ rights. And now that they have had such a major win around abortion, I think it’s freeing more energy to focus on opposing queer rights,” she says.

Bjork-James says it’s important to combat this rhetoric by redirecting conversations around child safety to real threats like poverty, lax gun laws and broken child welfare systems.

Woodrow says Christian nationalists can be reached most effectively by other Christians and Christian institutions, who can challenge their theological positions without being seen as outsiders.

But Mitchell says deradicalization is extremely difficult. Instead, she says energy should be focused on exposing and clarifying their hateful messaging, to help people understand what they need to fight and stop these groups from gaining new followers.

“You just don’t want more of them,” she says. “I think it’s really important work that needs to be done.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra